BRIAN’S ILLUSTRATED LIFE STORY

chapter 1

THE YORKSHIRE YEARS - FROM CHEMISTRY TO ART SCHOOL

1930 - 1949

- AT THE END OF EACH PAGE IS A LINK TO THE NEXT -

The beautiful county of Yorkshire is often referred to as “God’s own country” by its inhabitants.

“I am a Yorkshireman and by nature proud of it. I say by nature, because as far as I can recall, I have never met anyone from Yorkshire who has attempted to conceal their birthplace. If anything they have on introduction done quite the opposite, and so likewise have I.

“Yorkshire lies in the middle of the United Kingdom and has a quite unique geographical and social climate. The land and its inhabitants complement one another. Yorkshire people are, in general, proud, sharp, warm, kindly, down to earth and have a wonderful, often dark sense of humour. I would like to give the reader a vague idea of the place I will always feel part of.

“In the 1930s my county contained some of the most hideous industrial slums Britain had ever created, but it also had some of the most spectacular landscapes the British Isles have to offer. Visually, it was and still is an area of deep contrast. The Pennines overpower one with beauty to the extent of intimidation, so bizarre and gracious are its formations, its rocks and moors. Although not massive in scale, they seem to go on forever, magnificent, luring one deep into their shapes, moulds and curves.

“Winters were harsh. I have countless memories of blizzards, of walking, head down, trying to avoid the bite of the ice and snow on my skin, pushing against the wind, protecting my ears from the howling of the storm… fighting. I also remember the hot potatoes from the morning embers my mother slipped into my coat pockets to keep my hands warm on those walks to school, and that would be feasted upon later in the school playground.

“Like my mother, I was born at 5 Queen Street, Penistone, a terraced stone house of no consequence, that my maternal grandparents rented. I lived there with my parents, my four young aunts: Cathleen, Mary, Sally and Esther, and my uncle Harry. To this day I still do not understand how that house accommodated us all. It was indeed of humble size, containing only a front parlour (an old-fashioned word, used for living room, kept especially tidy for the reception of visitors) with an open fireplace, in front of which the family would take baths, a small kitchen and two bedrooms.

“Although we moved to a small and in those days ugly town called Hoyland Common when I was two, I continued to visit my grandparents for many years. My maternal grandmother was an amazing woman for whom I had a great amount of respect. She was thrifty: the type of person who always had a pound or two stashed away, ready for use in case of an emergency. At times, there would be more than ten mouths to feed, but she would never let anyone help with the cooking, for fear of wastage: cutting the vegetable peel too thickly or discarding valuable fat.

“My granddad worked eight miles away at the steelworks in Stocksbridge. There was no bus, so he and the other men from the village would walk. I never really liked him, the main reason being that as a young lad, he would send me up to the pub to fetch him pints of beer. It was not that I minded going up there, just that every time I brought his drink home, he would sip a quarter and then send me back to the pub to say they had served him short! The publican knew my granddad well. He was, after all, a good customer, and with a knowing look, he would fill the mug up again to the brim and tell me not to spill any on my way home. Each time I would die of embarrassment. To this day I have never drunk a pint of beer and, doubtless, that mortifying memory is the reason why!

“When I think of my father’s mother, the strongest image that enters my mind is one of her standing high above me wearing an ankle length, black leather coat. She was a devout Catholic, unhealthily religious and because my mother did not like her, we saw little of her. I never knew my paternal grandfather because he died when my father was twelve. This was a tragedy for my father because it meant he had to let go of his dreams and go down the pit. His identical twin Lawrence and he, being the oldest boys, had to support the family. They had no choice but to dig coal. Dad went down the pits most of his life and I hated it - man’s inhumanity to man.

MOTHER AND FATHER

“Most of the early memories I have of my father, Paul, (1905 - 1994) are linked with him riding his Panther motorbike which had won him the title of ‘the handsome tear-away’ by the neighbourhood. It looked fantastic and made a wonderful sound to my ears, akin to music. Whenever I heard that distinctive note, I would rush out to greet him back from his compulsory daily outing. Together on weekends, we would park the bike in the kitchen - which drove my mother crazy - and, as part of that ritual, I would bring him his blue overalls and tool box so that the machine’s maintenance could commence. Invariably he would strip the engine down entirely, supposedly to double check that everything was in perfect working order. In reality it just gave him a great amount of joy: mechanics and engineering were his passions. Had he not been forced to abandon his studies by an unkind destiny, he would at least have become a formidable engineer, or certainly gone on to achieve greater things. He invented the Rotary or what would later be called the Wankel engine when I was 15, long before NSU developed the concept. Lack of money and interest closed down his brilliant idea. Later in life he became a representative for a firm of mining engineers as well as quite an accomplished painter, enjoying art classes every Monday evening in Barnsley.

Elescar main colliery where Brian’s father Paul and twin brother Lawrence were forced to work by an unkind destiny.

Inspired by Brian’s motorcycling dad, Brewster Dick from Happily Ever After - Poems for Children by Ian Serrailler, OUP, illustrated by Brian in 1963.

“He was always very kind to me. He was not a strict man. (In Pelican, a book Brian would make in 1982, Paul, the young boy who finds, adopts, nurtures, and finally sets free a Pelican, is named after him.) My mother, Annie Oxley (1908 - 1984) was the disciplinarian of the two. She was the one who made us go to church on Sundays, do our homework, tidy our rooms, keep our lives in an orderly manner. Mum adored her children. She encouraged us in our every interest, leading us to believe that if we were to embark on any activity, whether physical or mental, it would only be of value if we put ourselves to it entirely. By instilling in us such a mode of thinking, she helped us find ourselves and by way of that, what we wanted from life. Mum was also very funny and a ruthlessly honest person to whom it would never occur not to speak her mind. She made a number of enemies. After my parents had completed the family, by giving me two brothers, Donald (1931 - 2008) and Alan (1937 - 2014) and a sister, Joy, born in 1941, we settled into a bigger house in the same town at 22 Springfield Road.

WORLD WAR II

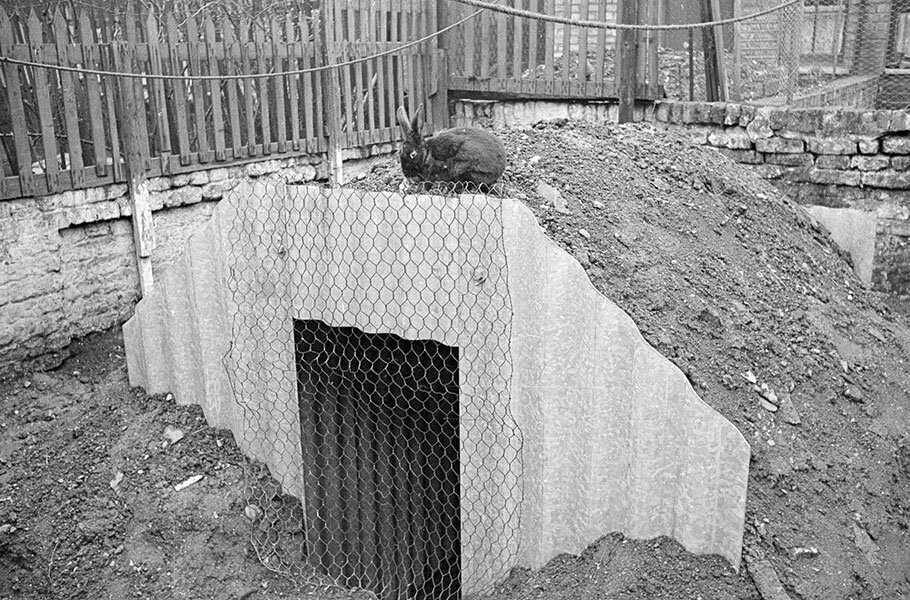

“A few months later the war came, and with it Anderson bomb shelters. Goodness knows what miracle they would have performed had they been put to the test. The few nights we spent in them when Sheffield was being bombed did us more harm than good, simply because the darned things just filled up with water when it rained. The war also meant being fed tablespoons of cod liver oil by my primary school teacher, the beautiful, tall, soft-spoken Miss Marron of St Helen’s, who, incidentally, I fell madly in love with despite her foul administrations. I loved my school too. The atmosphere I remember was one of warmth, aided by the open fires in front of which we would sit, thawing our frozen bottles of milk and sleeping in the afternoons, snug under woollen blankets. In retrospect my primary school was very progressive for those days. The walls were covered with ABCs and pictures. Learning processes involved shapes, colours, textures and games… although I do remember one ultra conservative teacher who believed in the principal of teaching through terror. Perhaps she was there to remind us of the harshness of the world. In any case I thank her for having made me know my times tables backwards.

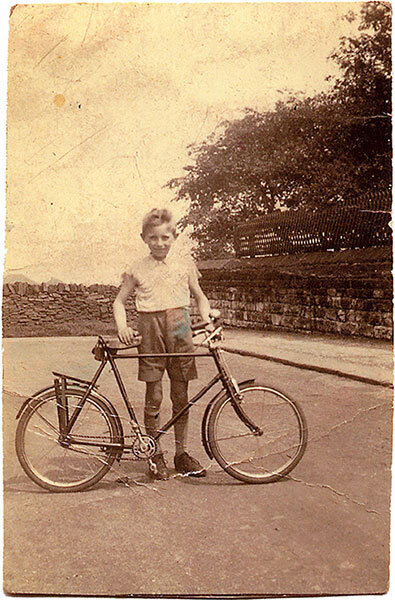

“Unlike the city children who had been uprooted by the British government’s emotionally wrenching ‘Operation Pied Piper,’ to be relocated with strangers in rural areas where the risk of bombing raids was low or non-existent, the war had little effect on my life at the time. I can remember cursing it for the shortage of sweets, but otherwise life went on as usual: food was rationed and so were clothes and shoes, but we never had many of those anyway. When not at school, I’d spend a lot of time riding my red Raleigh bicycle or building model aeroplanes. And then there was the cricket season! I played the game with a passion I believe many Englishmen share. When a pitch wasn’t available, we would play in the streets, halting traffic, having a whale of a time with brothers, sister, friends, anyone willing to join in. I believe they were the happiest days of my life. I also joined the Boy Scouts like many other boys of my age, with whom I went camping and exploring most weekends. Looking back at my childhood and quite paradoxically, due to world events, it was a time of much freedom and few restrictions. There was also my love for music.

THE PIANO

“Mum had bought a Wilson Peck upright piano from Sheffield, and it was my maternal aunt Esther who taught me the rudiments of its playing when I was eight. After a time and as I improved, it was decided I needed some real lessons and so I went to see a teacher in Wentworth, a place that was soon to change my life in another and quite unexpected way. This teacher owned a wonderful Steinway. The piano was a masterpiece, inlaid with mother-of-pearl and boxwood. I fell in love with its sound but the lessons were too expensive and after four hours they had to stop. Although I left with a broken heart, my passion for the piano and its classical repertoires never died. I would go to listen to concerts whenever and wherever I could, sometimes alone, sometimes with friends from Sheffield. Little was I to know at the time, that one very special day in 1963, I would acquire my very own semi-grand piano: a Blüthner that I still play to this day, if only to exercise my fingers.”

A DAMASCENE MOMENT

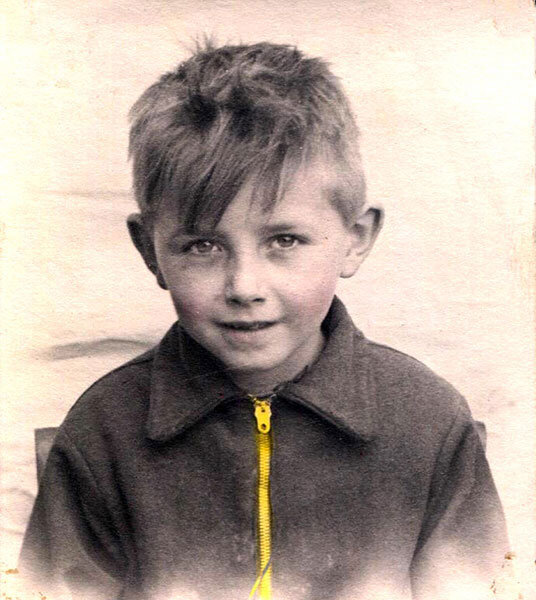

Brian’s parents were determined their boys would not become miners and encouraged them to study hard. To their satisfaction, Brian won a scholarship to a Grammar School in Sheffield - Delasalle College for Boys (1941 - 1946). “I remember,” Brian said, “getting on the bus, waving goodbye to my mother, brothers and sister, feeling so smart and proud in my green blazer and cap, both blazoned with the school’s colours of green and gold. My high school days were generally happy ones and being good at athletics, football and cricket - I was captain of the team, playing for Rockingham in the Yorkshire League - I was never bullied by other boys.”

In an article written in preparation for the centenary celebrations of his primary school St Helens, on the subject of its most illustrious past pupils, it is written that Brian “is remembered by his peers for his athletic abilities, his football skills and above all his talent as a cricketer. His pace bowling was legendary. Contemporaries will recall too his great musical talent, how from memory he would give impromptu recitals with spirited renderings of the Chopin ‘Military Polonaise’, the Beethoven Piano Concertos and the then topical ‘Warsaw Concerto.’ He had too the keen eye and the controlled hand of the artist. One classmate looks back and claims that a particular drawing done by him in 1943 proclaimed the international artist that was to be.

Brian continues, “In those days I intended to be a research chemist because I was good at the sciences. One day however, at the age of 16, in a Damascene moment, I was struck by a blinding flash on my way to a physics class, realising I was on the wrong tracks. A voice said to me, “Is this really what you want to do with the rest of your life?” And the answer was “No, I want to be a creator.” There and then I turned on my heels and went to see the headmaster to tell him I was leaving to go to art school. It was quite extraordinary, as I had no reason to think I had any talent for art. What was even more extraordinary was how supportive my parents were.

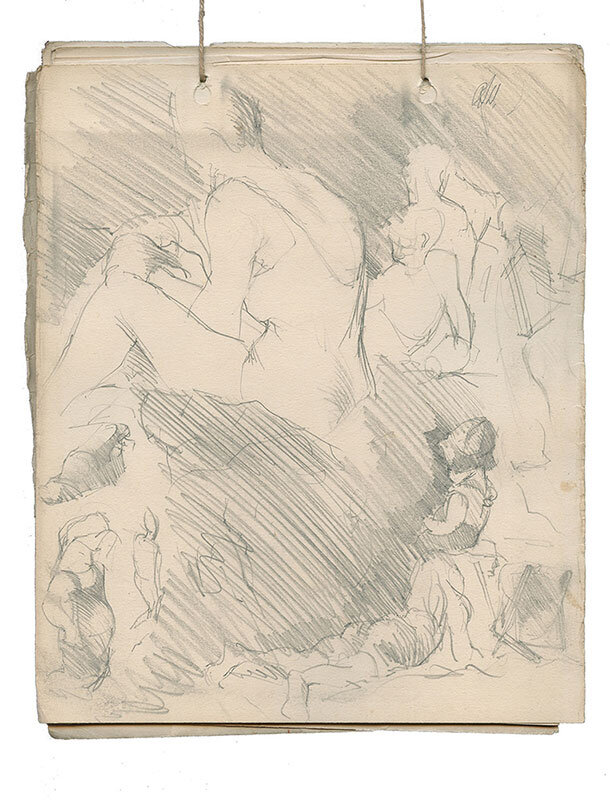

Roaring wood fires kept the nude models warm at post-war Barnsley School of Art.

BARNSLEY SCHOOL OF ART

“In Hoyland Common in those days, who the hell became an artist? That evening I discussed the subject with my parents who, in a typical show of faith, gave me their unadulterated blessing. My dad passionately believed education was the only way out. And so it was that I applied for admission to Barnsley College of Art and Design (1946 - 1949). My most modest portfolio consisted of drawings of different arrangements of cubes, spheres and triangles, plus a couple of drawings of motor cars which my pals had admired. I was offered a place and the school gave me good basic training which included courses in architecture, perspective, anatomy, still life and sketching from memory. There was only one teacher along with the headmaster and both disliked me. They considered me as some kind of weirdo because I admired avant-guard artists like Picasso and Klee, when they appreciated boring and conservative contemporaries like Russel Flint. I worked hard and the school appreciated my efforts as a draughtsman, so keeping me on despite our differences.” In a 2010 letter that Brian received from an old pal and contemporary, Charles writes, “There is plenty of information re your exhibition in the local ‘Whats-On-Civic’ News. How’s your memory Brian? Civic Hall? I could hardly believe it’s more than sixty years since we climbed the wooden stairs right up the top of Civic Hall. Life Class & a roaring fire to keep the model warm. Happy days.”

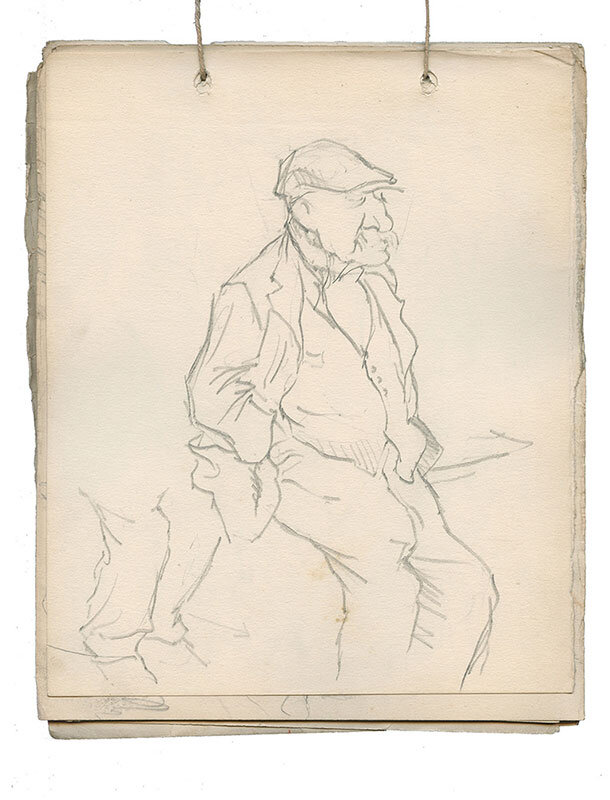

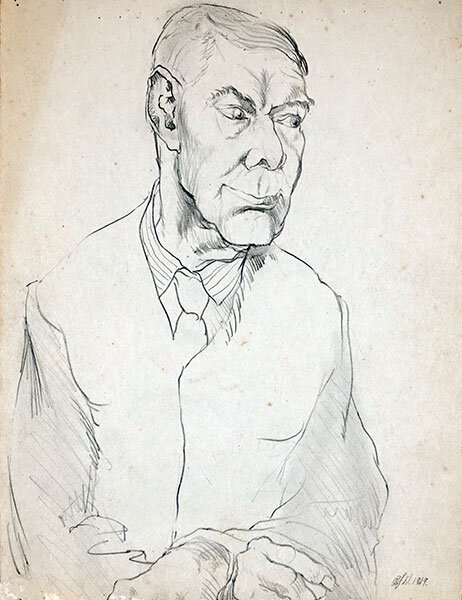

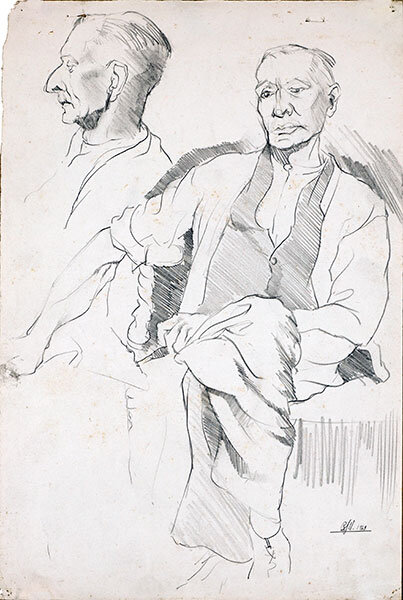

MY FIRST PAID JOB AS AN ARTIST

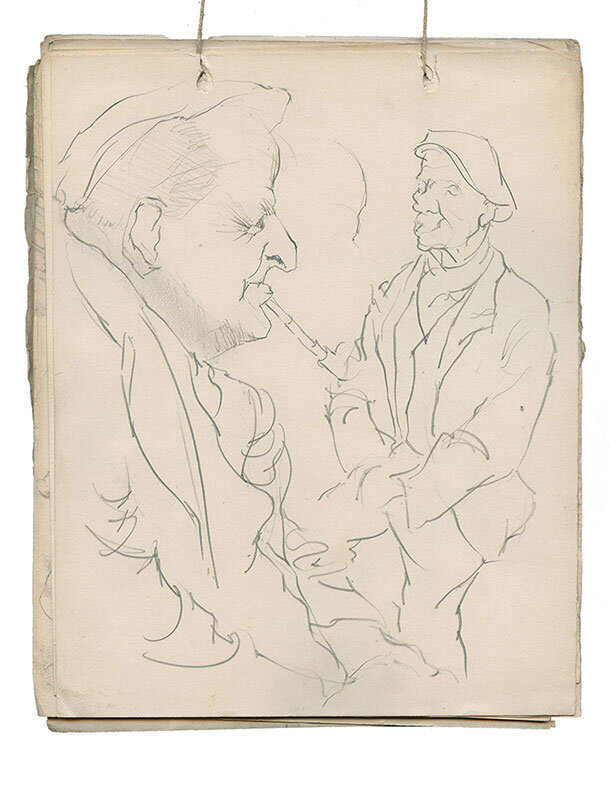

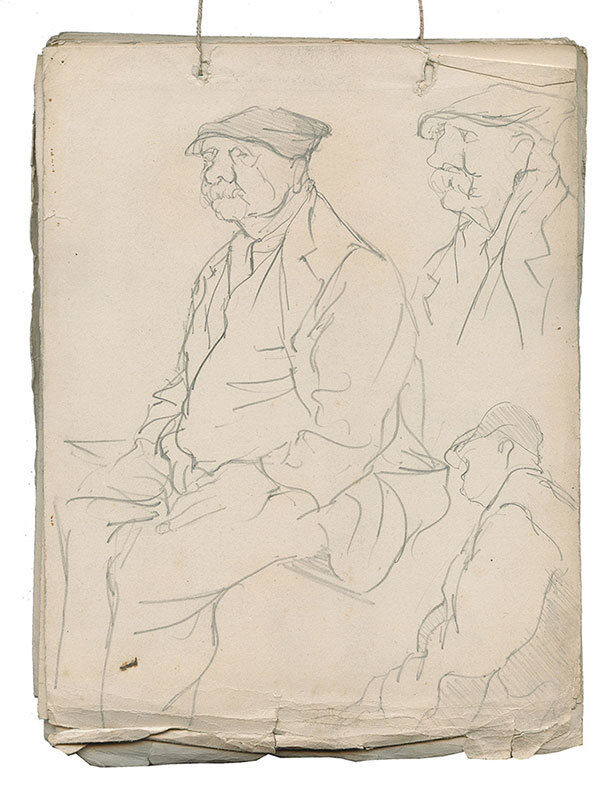

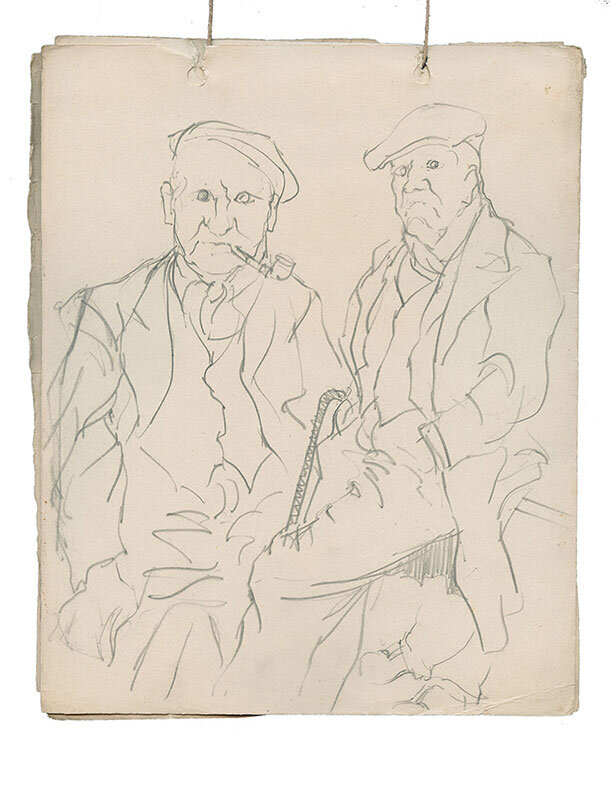

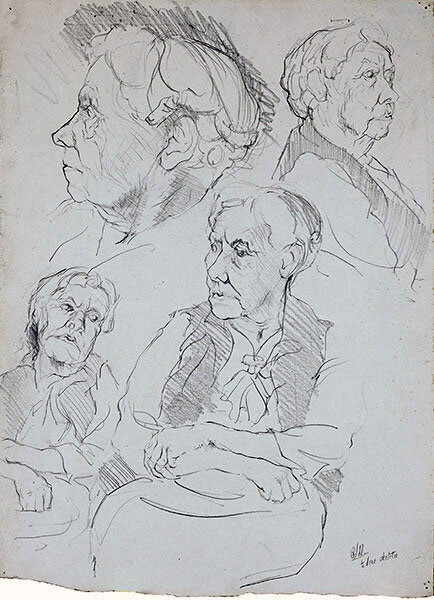

“Early on in the second year I got my first paid job as an artist. I approached the local newspaper, The Barnsley Chronicle, with the idea of going round the local working men’s clubs, interviewing retired miners whilst drawing them. Working men's clubs are a type of private social club, first created in the 19th century in industrialised areas of the United Kingdom, particularly the north of England, the Midlands, Scotland and many parts of the south Wales valleys, to provide recreation and education for working class men and their families. My idea was accepted on the condition that I only be paid for those portraits which were printed. That seemed fair enough to me, and so every weekend I would cycle to these different clubs to find my subjects drinking, chatting, playing cards or dominoes: time-beaten faces, lined by years of hard work and toil.

“The majority of the men worked down the pits like my father where, to hew coal, they would lie on their sides for hours in the dark and wet, in 2,5 foot high tunnels attacking the seam with their pickaxes. They were exposed to so many hazards, most severely the risk of gas explosion. Several of my drawings of these courageous men were published and I was over the moon. So, you really could make money from art! The project came to a halt however, after ten or so consecutive publications. Complaints had been received by the paper from several of my models as to the way I had depicted them: “Ugly” in their words.

WENTWORTH WOODHOUSE

“Curious, inquisitive and especially eager to learn, I needed inspiring subjects to draw. In my rounds of the local countryside, I had seen Wentworth Woodhouse. Just a fifteen minute walk away from my piano teacher’s house, it was a magnificent place built over a submerged lake and containing, I was told, some ancient Greek-styled statues that had to be worthy of study. I asked for and received permission to go there to draw them and what a place it was! Roughly Palladian in style, the largest private residence in the United Kingdom with the longest country house facade in Europe and some three hundred rooms. As I was busy sketching in the grand hall, a mischievous, freckled-faced young lady with the most startling green eyes peered over my shoulder, curious to see what I was drawing. She introduced herself as the chef’s daughter and nodded with approval as she flicked through my pad. I fell in love on the spot, there and then. I was 17 years of age and she a mere 14 and so I returned to the big house many a time with more than mere artistic motivation! Aurélie was the lady I would court and marry six years later and she remains my wife to this day. Aurélie’s father, Bernard, was an excellent Basque chef. He had been employed to practice his culinary talents in the owner, Lord Fitzwilliam’s kitchen shortly before the war. During the London blitz he invited Bernard’s Scottish wife Christina, along with their three daughters, Elizabeth, Marie-Jeanne and Aurélie, to join their husband and father to avoid being subjected to the terrible perils of remaining in London and the children being faced with forced evacuation.

Brian’s first paid job as an artist: 5 of the portraits that appeared in The Barnsley Chronicle

Aurélie, our mother, grew up at Wentworth Woodhouse, where her father, Bernard Ithurbide, a Basque man, was the Chef. It was there that she met our father, who regularly visited the great house to draw its art collection and notably its Greek-styled statues.

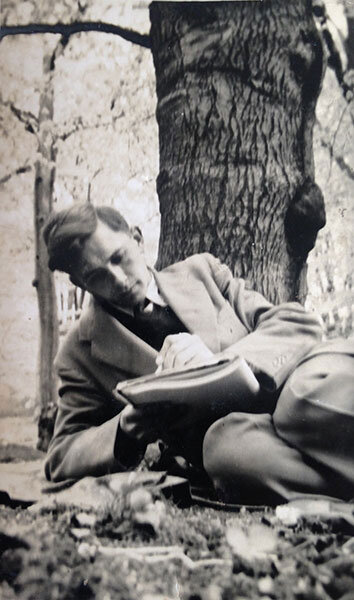

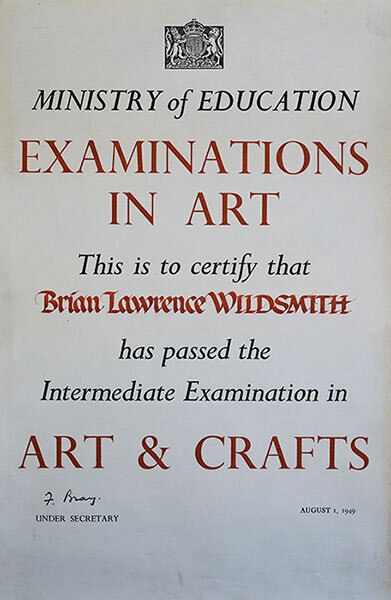

APPLYING TO THE SLADE SCHOOL OF ART

“At the end of the course, encouraged by the circumspect felicitation of my teachers, I decided to apply for admission to the Slade (the art department of University College, London) of whose fine art course I had heard excellent reports. To my consternation, I was told I was too late and would have to wait until the following January. This I found outrageous! Such typical institutional apathy not to inform its students of the most basic requirements for application to higher education. It was June and I panicked, knowing that by then, and through pure financial necessity, I would be swallowed into the mines or the steelworks and that would be the end of me. I had to act quickly. I telephoned the Slade and demanded to speak to the Principal who, to my surprise, invited me down for an interview. I had received no advice as to how to present a portfolio, so I packed my bags, along with what I believed to be the best of my work and took the train to London. I was greeted by Professor William Coldstream, a small unimposing man who, when I handed him my work, rushed off, leaving me to contemplate the paintings hanging in his study. He returned half an hour later, huffing and puffing, having unsuccessfully searched for a colleague throughout the entire building. Of his own accord, he accepted me as a future student and I was awarded a scholarship of £203. Term started in September 1949.”

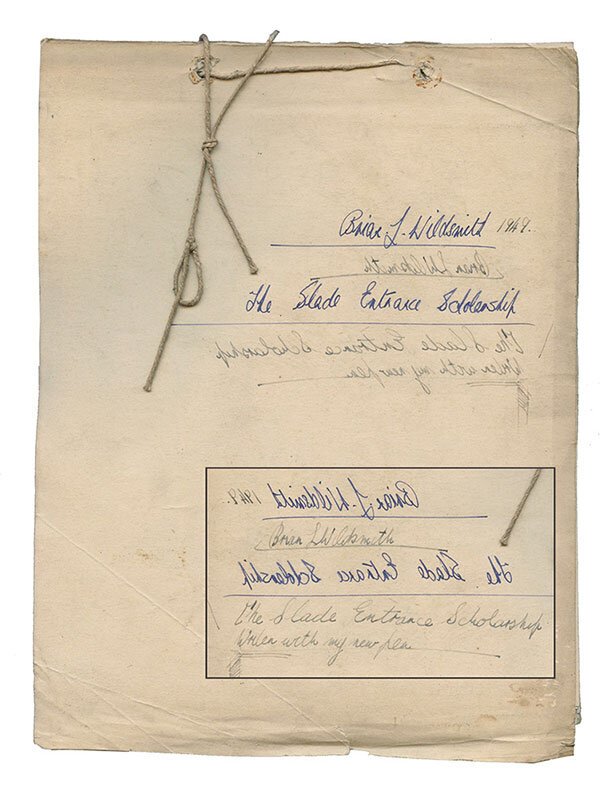

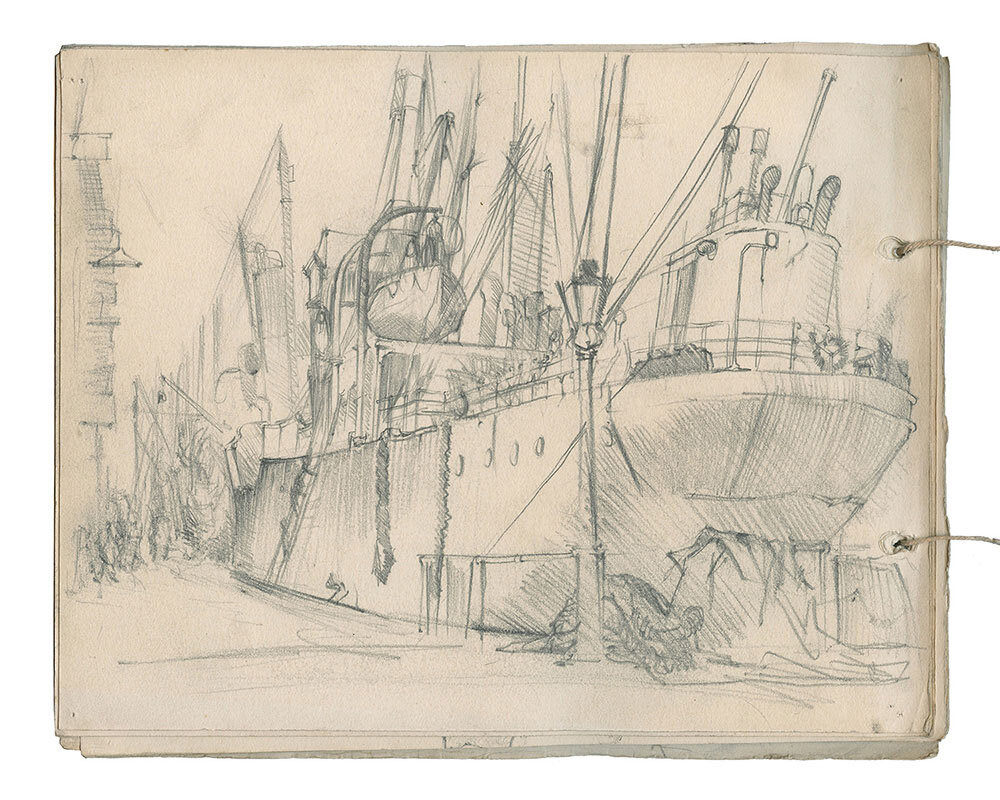

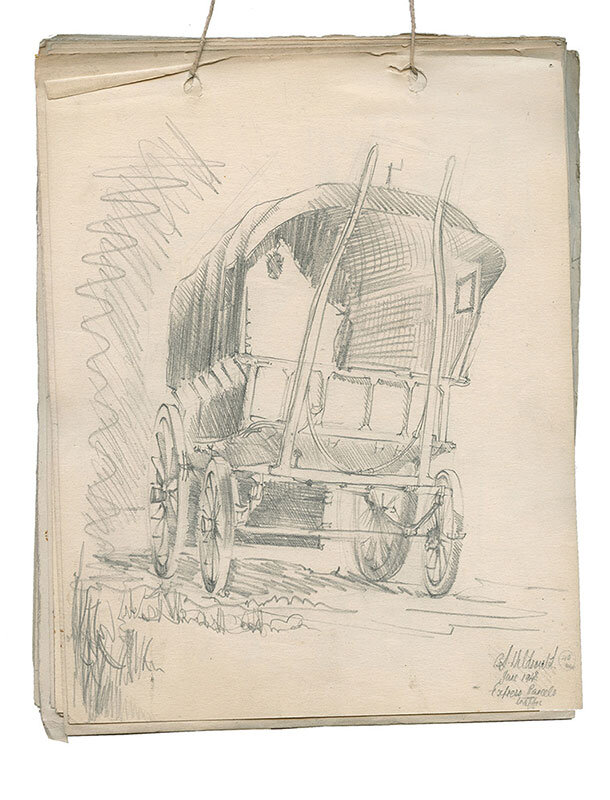

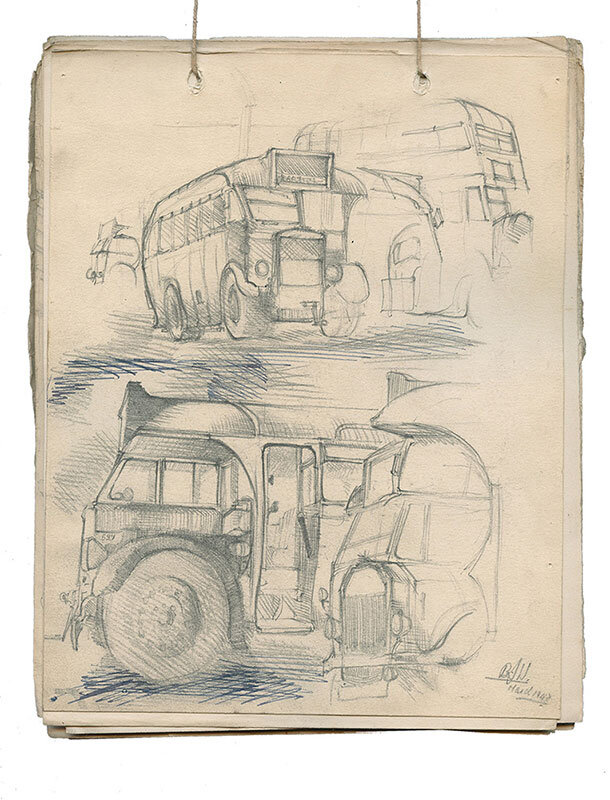

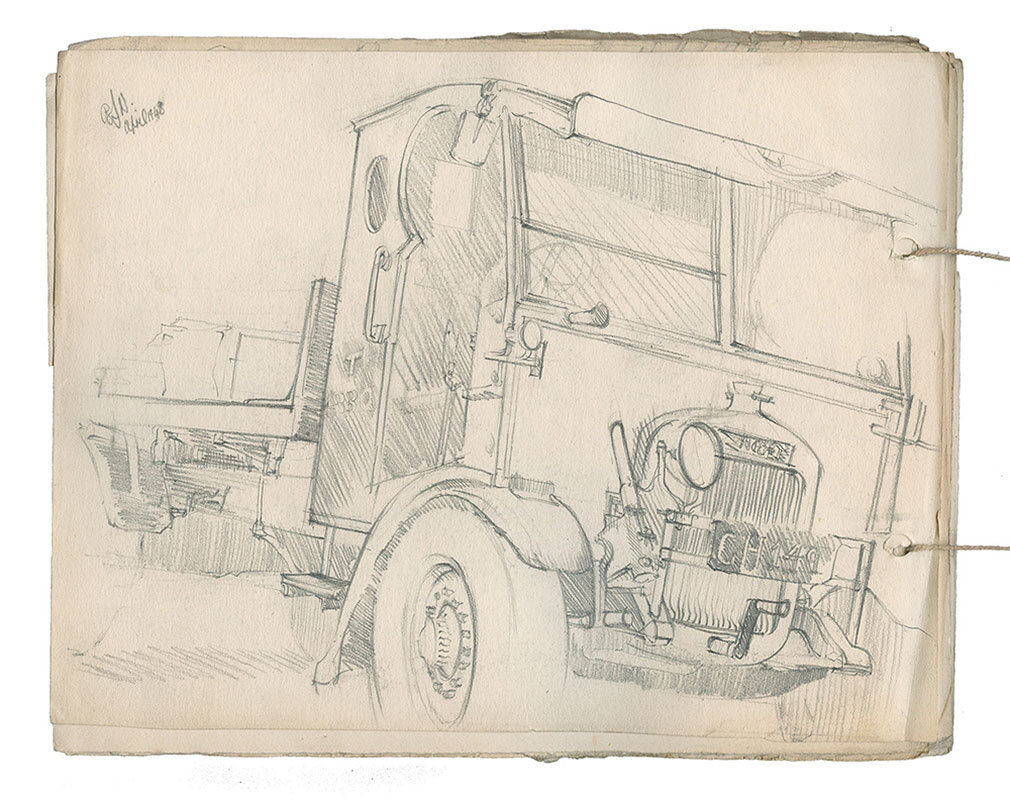

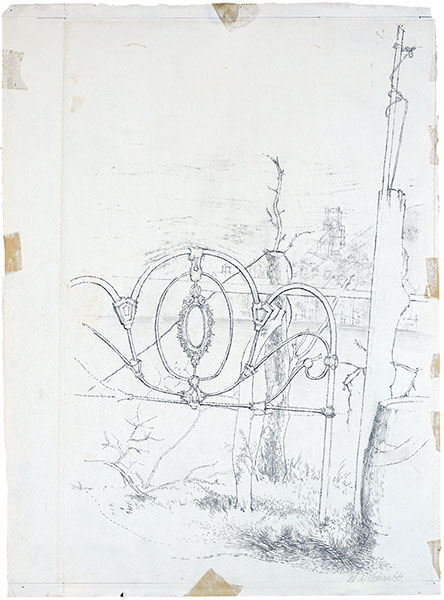

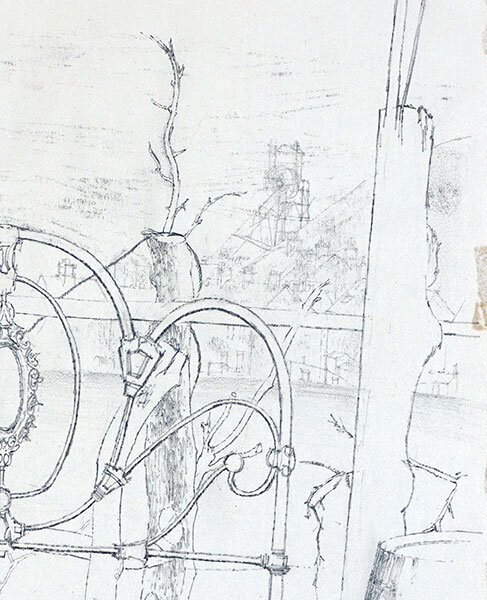

Extracts from the portfolio Brian submitted to the Slade School of Art in 1949 in hope of admission and a scholarship. Brian was ambidextrous and as a young man often wrote in mirror fashion, notably in private correspondence with Aurélie. In the outlined rectangle (1st image) I have flipped his writing for easier legibility.

And the news received one happy day in August 1949.