BRIAN’S ILLUSTRATED LIFE STORY

chapter 6

FOR ALL OUR TOMORROWS

2003 - 2016

I HAVE NO MORE TO SAY

Finally now, at 73 years of age, our father talked of ‘inspirational fatigue’ and, unwilling to repeat himself, he stopped creating books. “I have no more to say,” he said. With 82 titles to his name, and over a period of over fifty years, he had painted close to 2000 illustrations, made hundreds of line drawings, 100 or so paintings, countless sketches, at least 137 magazine covers, many posters, silk screens and other designs. Understandably his workaholic tendencies had faded. When he now sat on his terrace with a glass of wine and his favourite cigar, it was for the sole sake of contemplation. He needed peace and quiet more than ever, but something had changed. There was no longer the need or call for a creative vision to emerge. From our point of view, the truth of the matter is that despite our understanding his choice and need for rest, we were concerned that creative inactivity would lead to decline. To the outside world his achievements were immense. To him, he was just doing what he was born to do… He was doing his job. But that ‘job’ kept his mind ticking over, kept him alive in every sense of the word. With such a strong disposition towards solitude, one brought on by necessity, habit and desire, what would happen now?

At the Reform Club in London, 2000.

Thankfully, the outside world wouldn’t let him just kick back on the terrace and dream full time, as that same year, in 2003, he was back to Japan for the opening of a large-scale retrospective of illustrations from fifty of his book titles. He was delighted. It was MetM Co. Ltd, Michiko Nomura’s company, who organised this touring exhibition from the illustrations Brian had lent her over the years and sent to Japan at her request, to supposedly feed her museum. It was called Fantasia from a Fairyland and opened at the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum of which, writing in the exhibition catalogue, Brian wrote: “A number of years ago I visited the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum. I was amazed and delighted by the superb quality of the exhibits, a truly wonderful collection... it is therefore with humility and gratitude that I thank the Fuji Museum for the great honour they bestow on me by exhibiting much of my life’s work covering forty years. I shall be forever grateful.” The exhibition then toured Japan for just over a year, after which the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts in Taiwan had “the pleasure to introduce the precious, original works of splendid illustration from the distinguished British illustrator to the people of Taiwan.”

In Japan, a staggering 1,35 million people visited this retrospective.

A few years later in early 2008, and back in Brian’s homeland, BBC Bristol was commissioned by BBC4 to make a three-part documentary about children’s books named Picture Book, scheduled to be aired that same year from 5th - 19th November. For part one, called When We Were Very Young, the producer and director Merryn Threadgould contacted Brian, asking him for a short interview about the concept behind, and making of his 1962 award-winning ABC, which he accepted. Professor Martin Salisbury who, amongst other illustrators, authors and a pedopsychiatrist, was also a guest on the programme, put Brian’s work into its historical context by saying, “Wildsmith… was incredibly influential on the 20th century illustration scene… His ABC is a riot of colour and texture and he was one of the very first, probably the first, to use paint in illustration in such an exuberant way.”

As an extension to this thought, Olivia Ahmad, curator at the House of Illustration in London, in her 2019 essay about historical and contemporary British children’s books, written to accompany The British Council’s touring Drawing Words exhibition, clearly specifies how, “Wildsmith’s explosive colours and painterly textures were a sensation when his ABC was published in 1962.” The book is recognised as a historical reference for the ‘expressive approaches’ to image making in children’s publishing in the early 196Os cultural revolution. Olivia chose to demonstrate this with Brian’s butterfly from the book, below. Interestingly, Mabel George’s ‘championing’ techniques are also brought up in this essay as are the other significant artists of this period.

The now infamous butterfly that Brian painted for the second letter of his first book back in 1962 that helped launch an astonishing career of creative freedom devoted to children’s education through art.

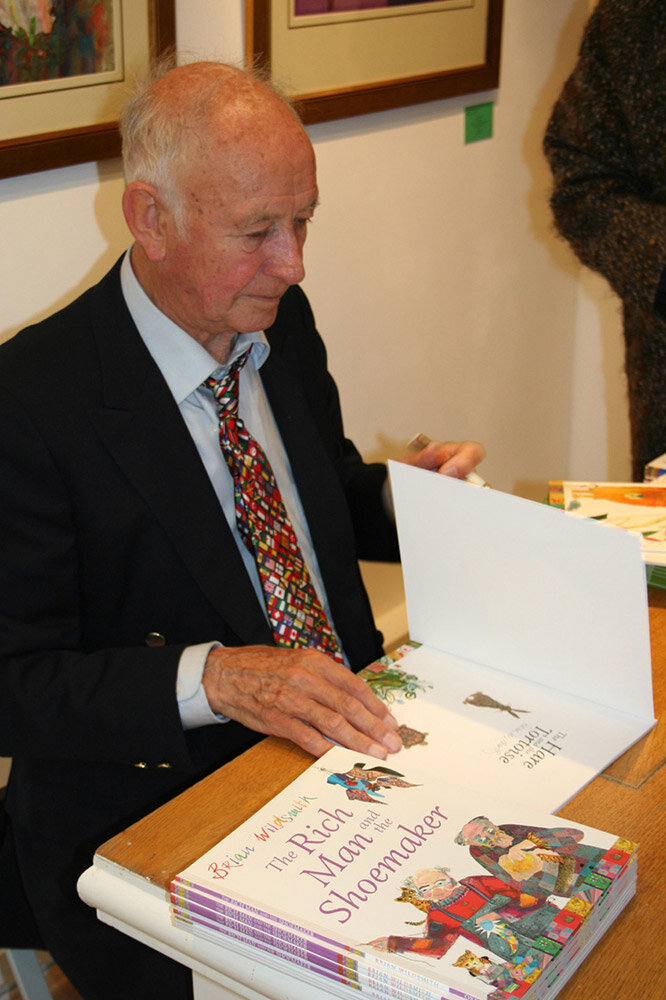

In April 2010, John Huddy, owner of the Illustrationcupboard Gallery on Bury Street, SW1, in central London, specialising in the best modern illustrators’ works from around the world, presented an exhibition of Brian's art. It was a reflection on his 50 years as an illustrator and author and turned out to be the best attended and best-selling event in the gallery’s 25 year history. At the opening, Brian, who had never lost the lively twinkle of his Yorkshire accent and was still the eloquent speaker of the past, gave a speech full of warmth, mixing anecdotes with humour and humility, thanks and appreciation. There was also that hint of old remorse about the very early review, written by a critic that the world has long since forgotten, and which, despite its violence, had helped convince Oxford University Press they had an artist on their hands. Helen Mortimer, his editor since 2004 and her team, came down from Oxford to show their appreciation and support and publicly acknowledge “the pleasure it had been working with him.” As guests were raising their glasses to his genius, a mixed generational queue of good-humoured admirers and fans was forming down the street, waiting for the opportunity to see the works, meet Brian or have him sign one of their treasured and often dog-eared books.

Brian once wrote “Every artist who's ever lived wants to be appreciated. It's just part of being an artist, whether you're a singer, a musician, a painter or an illustrator. We want to be appreciated – that's why we do it. Our art is our expression, but it's really for other people.” ‘The Master of Colour - Brian Wildsmith at 80,’ John Huddy’s hugely successful exhibition, was a just reward for that. Sadly the Gallery closed in 2019, due in no part to lack of support or success but because of ever-rising rent prices demanded by the Crown Estate.

During this same period, Liberty Art Fabrics, for their Spring 2011 collection, used several drawings of aeroplanes from Brian’s Amazing World of Words which were reproduced in repetition on very fine Tana Lawn cotton, and in four different colours. The design was also used by Nike for a limited edition of ankle-high, lace-up trainers, but we are not aware of the circumstances surrounding this deal.

Liberty Art Fabrics, used a repeat pattern of aeroplanes from Brian’s Amazing World of Words, also used by Nike for trainers seen here being made by the poor shoe-maker from The Rich Man and the Shoe-Maker.

In 2013, Brian was contacted by the Korean agent and gallery owner Kyeong Ki Hong, known as Guy Hong to his Western friends. Samsung were launching a ‘Save Water’ campaign to promote their ‘water-economical’ Bubbleshot washing machines. As part of this campaign they were commissioning illustrious illustrators, ten in total, to illustrate this theme for a book, video and other media. With Simon’s help in Photoshop, and using imagery from a variety of books, they created the composite image below that would also be chosen for the book cover.

The last creation: A composite Image comprising images from a dozen books realised for Samsung in 2013 for their Bubbleshot water-saving campaign.

Continuing his 80th birthday celebrations, Oxford University Press co-organised two other events. The first, ‘Brian Wildsmith’s Animal Gallery,’ was held at Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne from 1st April - 18th July 2010. This exhibition focused on the works from the recent publication of Animal Gallery, a compilation from Fishes, Birds and Wild Animals. Considered “as fresh and entrancing as they were when first published forty years ago”, and showcasing “Wildsmith’s most beautiful animal paintings to inspire a love of nature and a respect for animals from the earliest age.” Scanned artwork was projected in their ‘book den’ reading area to create a “beautiful, sensory, immersive space.”

Secondly, the Panorama exhibition space at The Civic in Barnsley, only a few miles away from Brian’s birthplace, played host to Brian Wildsmith in Yorkshire, 23rd September - 5th November 2010. Alison Cooper curated this small exhibition from the Illustrationcupboard Gallery’s collection in London. The event was presented as “a rare opportunity to see his illustrations outside the Brian Wildsmith Museum of Art in Japan.”

Brian was delighted to be present at all these events. He was honoured and thoroughly moved by all the praise he was receiving, but the trip became a physical and intellectual strain for a man who had become so accustomed to a quasi hermit-like existence. Additionally, back at home, Aurélie had become unwell. It was not particularly serious, and she was in good hands, but Brian wanted to be with her. This quite natural wish would however be somewhat complicated by nature, as Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano was in full eruption at the time, closing airspace over Europe. Undeterred, he opted to travel home by train. We were a little concerned. The return trip would be lengthy and tiring, involving several railway station changes, notably in the hustle and bustle of Paris. Brian did not possess a cell phone, let alone a smart one, and being such a dreamer, he had the reputation for getting easily lost. He rang us from one of the last remaining telephone booths at St Pancras station to say he was leaving, and two days later, turned up exhausted but happy and smiling. He had taken the Eurostar through the Channel tunnel for the first time - that which had inspired his 1993 bilingual book The Tunnel, spent the night in Paris after missing a connecting train bound south, sat on a bench in Marseille for far too long absorbed in his newspaper, thus missing another, but he managed to get home, determined as ever. We had underestimated him.

ONE RARELY FORGETS ONE’S ORIGINS, THEY HAVE A TENDENCY TO PURSUE ONE

For many years our father had chided the “dull, lightless and drab” northern English environment that he had grown up in. This, we know, had more to do with the dingy tint created by the exploitation his, and so many other fathers had been subjected to, and which coloured his life there, than his immediate sociological or geographical environment. Yet, as an older man, and encouraged by Aurélie, they spent hours reminiscing about Yorkshire, their family, their friends, the dales, their bicycle rides, their first encounter, always with laughter, often tears of them, and with most affectionate nostalgia. For the Yorkshire Post magazine in 2006, Sheena Hastings wrote, “He left Barnsley nearly six decades ago but the accent is still unmistakably there though muted by years living on the French Riviera. However if you lead Brian Wildsmith into conversation about his birth in Penistone and the years growing up in Hoyland, good South Yorkshire vowels are quickly restored to full bloom. He may be gazing out of the window at purple wisteria nurtured in a balmy southern climate but as he talks he is almost back there in Springfield Road playing cricket with his pals after-school or riding his bike across the landscape punctuated by pitheads.”

As many of you reading this story who have, or once had ageing parents, or indeed are elderly yourselves will know, the latter years of life confront one with multiple challenges: mobility, physical and mental health, the issues of distances separating families. Some will seek refuge or comfort in their faith, some in terrestrial pragmatism, others in both. What contemporary western culture does for few of us however, is prepare one for the inevitable. In caring for our ailing mother with a characteristic cocktail of love and stubbornness, our father had exhausted himself. For too long he refused the help he clearly needed until, in extremis, he surrendered and allowed us to organise what turned out to be a veritable ballet of nurses, chiropractors and carers. Despite all of this manpower, that the French healthcare system provides at a very low cost to the patient, serene twilight years appeared unlikely.

Together, we children had come to the conclusion that confiding them to a nursing home was the only viable solution to avoid further accidents or other problems of a serious nature. We had discussed this possibility on numerous occasions amongst ourselves but frankly dreaded the moment when we would share these thoughts with our parents. To our utter astonishment they were both open-minded and listened to our propositions, possibly secretly relieved. We had done our homework and a lot of investigation. In earlier years, if the subject were barely touched upon, due to our foreseeing future issues linked to the impracticability of their hill-side home - 57 steps from the road up to their sitting room, kitchen and bedroom for example, and which had made our now invalid mother mostly captive of her own home - our father had always responded in the same way, and not in a calm tone of voice: “They will have to carry me out feet first,” he would shout. Of course, he so cherished his independence, his daily outings for food shopping, and his weekly Sunday drive up into the back country, that had now become a danger for those he crossed. Things however had changed. Deep down he knew he could no longer cope.

The Côte d’Azur playing host to a large, ageing and affluent population, a great many nursing homes are on offer. It is big business and there is severe competition as to which can provide the best service in the most desirable environment… at a cost. Our parents’ and our priorities were straightforward: great views, hopefully to rival their own, good food, spotless cleanliness and of course, friendly, efficient service. Residence Sophie in Grasse was hands down favourite and as soon as two bedrooms became available, they moved in.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. Our mother, who had been so vivacious in earlier times, had grown a little too accustomed to the solitude that was so vital for her husband. She had difficulty in socialising with others quite frankly, while our father never fully recovered from the wear caused by the years he cared so diligently for his wife. It is most fortunate that Rebecca, who had moved back to her parents’ home to be closer to them, and help with her father’s affairs and work, did an extraordinarily selfless job of visiting them several times per week, keeping them supplied in cigarettes, cigars and tactile love. Three times a week, she would chauffeur them around the beautiful and mountainous back country roads - the famous Route Napoleon was a favourite - in the glass-roofed car she had bought specially for the purpose, always with a halt at the summit for ice cream, a glass of rosé or both.

This sleeping girl taken from Brian’s book My Dream so reminded us of our mother that we used it to announce her passing to friends and family.

After 18 months in this home our mother passed away in the early evening of Monday 25th May 2015. She had had quite enough, thank you very much and wanted to go. She was a most proud lady, both elegant and distinguished in her earlier years and she never adapted to her elderly condition which she endured with indignity, often repeating the words “don’t grow old” to us. She also believed she would be reunited with her sisters Marie Jeanne, (who we called Molly) and Elizabeth both of whom had died many years ago, and that she had missed so. Despite her extreme fatigue, there was reason enough for her to rejoice, and in those impending hours her beliefs, hopes and faith helped her to prepare. What only the privileged few knew of our mother, was just how strong and determined she could be.

Our good byes were held in the pure and simple barrel-vaulted beauty and peacefulness of Castellaras’ XI century chapel where Aurélie had so often retreated to pray, or to just get some peace and quiet, away from her boisterous children. All those present in the village at that time came to pay their last respects, to a mysterious lady for some, a discreet friend for others, and an unconditionally loving mother for us. Following her cremation in Mandelieu, west of Cannes, her ashes were placed in a pyramidally lidded and lustred square porcelain box her son had made for her one Christmas. It had a silver moon at its apex to help her on her journey. With immense delicacy, Brian then placed it on a high shelf in his room back at the Résidence where it would remain for fifteen months.

On the 26th August 2016, the telephone rang. It was Rebecca. “Dad has been rushed off to hospital. It’s serious. You must come quickly,” were the dreaded words she spoke in a voice tainted with fear and anxiety. Brian had enjoyed good health most of his life but his one weakness was intestinal. He had endured a number of complaints that only increased in severity with the passing years. This time he had suffered an intestinal rupture and the complications were serious, multiple and reverseless, according to the head doctor. “He will not make it through the night” said he, convincingly, ignoring both what this man was made of, as well as his immense attachment to life.

Well this Yorkshireman made it through that night, and the next, and indeed the one after that, with three of his children at his bedside (Anna was far too ill to be present) or taking turns to ensure he was never alone. On the fourth day, his condition worsened still further and he slipped into a deep sleep. Clare placed a pair of headphones on his head and played Chopin’s Nocturnes. Shortly afterwards, and quite suddenly, he stirred from his silence, murmuring words, some coherent, others less so. What was most clear though, was that he was acting out what to him was a most vivid scene: He had travelled back seven centuries and he was grinding pigments. He was an artist in the Italian Renaissance and he was preparing the colours for the fresco he was painting. His mind and creative soul were still quite alive and bubbling, but his body could no longer keep up.

Until the very last moment, he was still the magician of colour.

The Castellaras village chapel from where we said our good byes and farewells to our mother in 2015 and to our father in 2016.

We gathered in the same Castellaras chapel that he too so loved. He wanted Mozart’s Requiem played at his funeral, “the whole damn piece,” he had told us one day long ago. Of course we obliged with all 55 minutes of it. Peter Madan, the British priest, practicing on the Côte d’Azur, who celebrated the service, said very rightly: “Brian grew up in a very acute consciousness of what it’s like to earn your bread. His life had a meaning, a sense of purpose, a direction. We are here today not only to mourn, but to remember that someone who is able to communicate with several hundred millions of people through their art has lived a good life. Brian had the added blessing of being able to leave something to the world not only for today but for all our tomorrows.”

Aurélie Janet Craigie Ithurbide Wildsmith

17 11 1932 - 25 05 2015

Brian Lawrence Wildsmith

22 01 1930 - 31 08 2016

Anna Wildsmith

08 03 1963 - 31 09 2016

THIS WEBSITE IS DEDICATED TO ANNA

An Atelier Wildsmith Production:

research, writing & cooking: clare wildsmith

writing, photography & website design: simon wildsmith

organisation, filing & general knowledge: rebecca wildsmith

To the best of our knowledge, all information/content on this website is correct.

May our parents and sister Anna Banga rest in peace