BRIAN’S ILLUSTRATED LIFE STORY

chapter 4

FRANCE, “ARTISTIC MATURITY” AND 100 PAINTINGS

1971 - 1989

- AT THE END OF EACH PAGE IS A LINK TO THE NEXT -

CASTELLARAS - A VILLAGE FOR COLLECTIVE SOLITUDE

As it is for so many artists, light was very important to Brian. Having considerably more sunshine was decisive in his resolution to leave his homeland. “When there is no sun, I feel depressed,” he commented in more than one interview, as if an overcast and grey day in Yorkshire or London was worse than anywhere else in the world. Having said that, and in total objectivity, statistics have proved more sunny days on the French Riviera than in Sheffield, Barnsley or London! The glorious suns that appear in the majority of his books are reminders of this craving. And so it was, that in 1971, the very tidy and polite residential outskirts of London were abandoned for a strange hill-top village, where the lines between sculpture and architecture are blurred. Castellaras was imagined and created by Jacques Coüelle (born 1902 in Marseille - died 1996 in Paris). He wasn’t an architect in the strictest sense, preferring to call himself an ‘écologue, a sculptor of living houses’. He really was more sculptor than anything. The framework to his house creation was unique: he designed around the principle that the most comfortable place for all species is the mother’s womb and so, if a straight line is found in one of his buildings, it is only there to set off the numerous curves. Space and time, the influences of the sun, the moon and even the earth’s magnetic fields all had their part to play in the layout and structure of many of Couëlle’s houses.

The village of Castellaras Le Vieux where the Wildsmiths lived from 1971 to 2013, was built by Jacques Couëlle in the 1950s and 60s on an olive grove around the Château, also built by him in the 1930s for a wealthy American art collector. In an over populated and exploited Côte d’Azur, this private village and its vast unspoilt grounds provide a quite unique haven of quiet and peace that Brian naturally fell in love with.

In Castellaras, 91 houses are joined together so ingeniously, using a system based on horse blinkers that each one enjoys total privacy. Called “the village of collective solitude” by its creator, it sure lived up to its name! From his workroom at the top of our house, Brian could look out over hills covered in pine, olive and mimosa that roll down to the coast and the Mediterranean sea five miles away; stare at the magnificent sunsets that light up the sky behind Grasse, and just marvel at the spectacular view that, on a clear day, allows one to see Corsica 100 miles away to the east and the Estérel coastline twenty miles to the west. The fantastic views were due to the village’s elevated position and our house facing directly south.

The quite unique setting of the village was not the only quality that appealed to our parents. Having been built on a 160 acre site with a secure entrance and nightly patrols, it also offered a huge and safe playground for their children to roam around freely and grow up in total safety. Brian wrote, “I believe our children were happy there, especially the younger two who, by not living in a city, were able to sneak off for hours, exploring the woodlands surrounding the hill, bicycling to nearby villages, running, jumping and playing games in the grounds, swimming and splashing around in the communal swimming pool, eating fruit to the point of being sick, from the tops of cherry, apricot and fig trees, collecting olives from the grove and participating in the many activities kids are likely to do when allowed freedom of space.” The least that can be said, is that life there contrasted sharply with that in London and we can now appreciate how privileged we were to be surrounded by so much space and beauty. Being essentially a place of holiday homes, there were two seasons: winters, where one had to make one’s own fun and entertainment, with or without the three to six other kids whose parents had elected to live there full time and summer, when the population decupled and the village exploded with life as another forty or fifty kids arrived from all over the world. The same ones year after year, and so strong relationships and friendships were formed and a lot of fun was had, mostly around the massive communal village swimming pool and at various levels of innocence as the years inexorably rolled on. If our parents had known the half of it!

With a glass of wine and a cigar, Brian spent hours and hours on the terrace with its spectacular view. Seemingly dreaming, he was often meticulously planning the stories he would tell. Once back in his studio, he had it almost all worked out. The book would unfold to the paper with freedom and ease since the hard bit had already been done.

THE PIANO

Brian’s prized Blüthner piano was bought, “Long before we could afford it,” remembers Aurélie. “We had three children to feed and no curtains, but in his dogged determination he got up early one day in 1964, took to the queue and paid £403 for it in a Harrods sale.” It accompanied the family to France and sat almost surreally on the second floor mezzanine. It had been placed there with delicacy by a crane under the anxious and concentrated orchestration of its owner. The crane’s jib was expertly telescoped up from the road 100 feet below, shaving an olive tree and through a top floor window, to the apex of the ceiling. This allowed the piano to be hoisted up from the sitting room floor to the mezzanine. It had been hauled up the outside steps so far, strapped to the back of one immense man. Getting it out forty-five years later was a less slick operation. The more mature and formidable olive tree now forbade a reverse operation. The mezzanine's sculpted plaster balustrade had to be broken up in part, so that the wooden-boxed piano could be slid down on a 45° ramp of raw timber, held by a trio of muscly Latvians. This same operation being repeated four times, on different levels of the house and terraced garden, until finally it could be loaded into the removal lorry.

During his life, our father would often play the music of Chopin, Schubert, Mozart, Liszt or Beethoven that he so loved. It was such a treat and we encouraged him at every opportunity we thought he might oblige. That he played beautifully, there is no doubt, but his modesty in this domain meant that when congratulated for this, he would most often just reply, “It keeps my hands in shape.” His playing Chopin's Nocturnes or Preludes to nurse us to sleep when we were little are such warm and powerful memories, that the instrument is enveloped in a sentimental shroud of sacrality. It is currently being restored back to the state of the great instrument that it should be.

Brian said he had found not only his ideal home, but also, and most importantly, a place to work in solitude, which is what he required to create. Many of the 19th and 20th century’s greatest and most celebrated artists had chosen this part of the world to live and work. Chagall, Matisse, Cocteau, Renoir, Modigliani, Cezanne… Picasso was a neighbour! Brian would sit on the north or south terrace for hours on end staring out seemingly into space. It was his way of feeding his mind and soul, refuelling his creative self and thinking about or planning projects to come.

A water colour of the view from Brian’s studio. To the left, on top of the hill is the Centre Hélio Marin in Vallauris and in the centre is Mougins, which must hold a record with its 78 restaurants, of which Le Bistrot de Mougins was the family favourite in the days when it was run by Alain and the chef Jean-Pierre.

Above: a series of five original and exquisite posters created by Brian in the early 70s.

The first four were commissioned by his American publisher Franklin Watts of N.Y.C.

BACK TO WORK

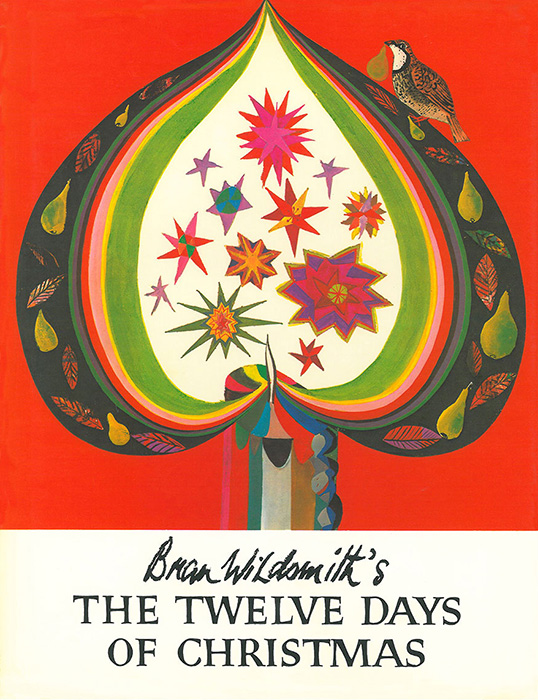

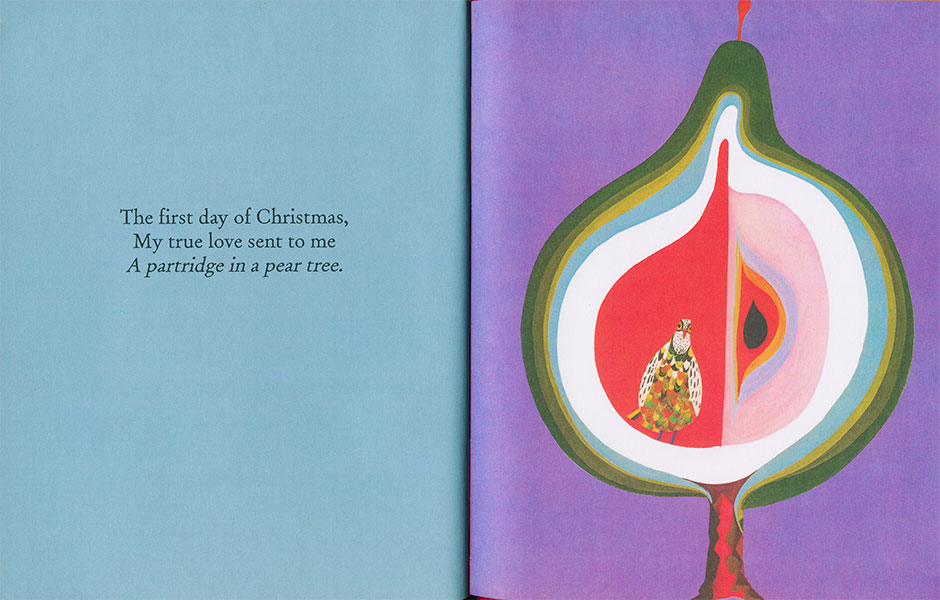

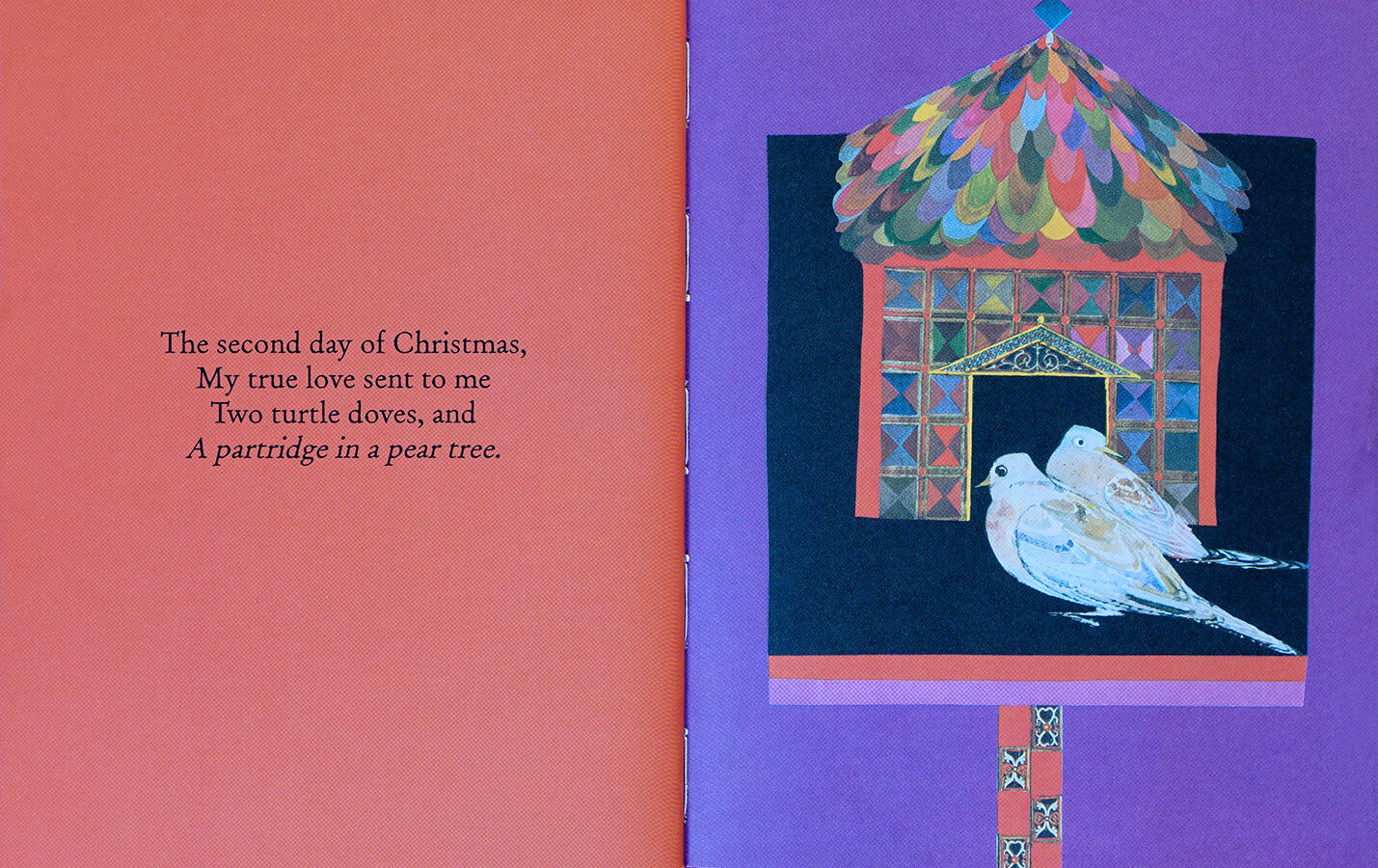

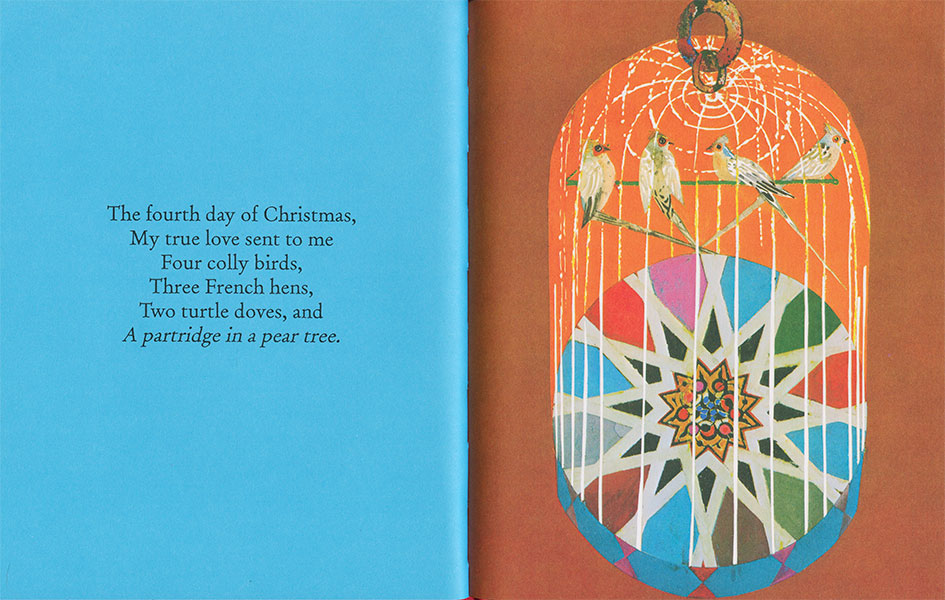

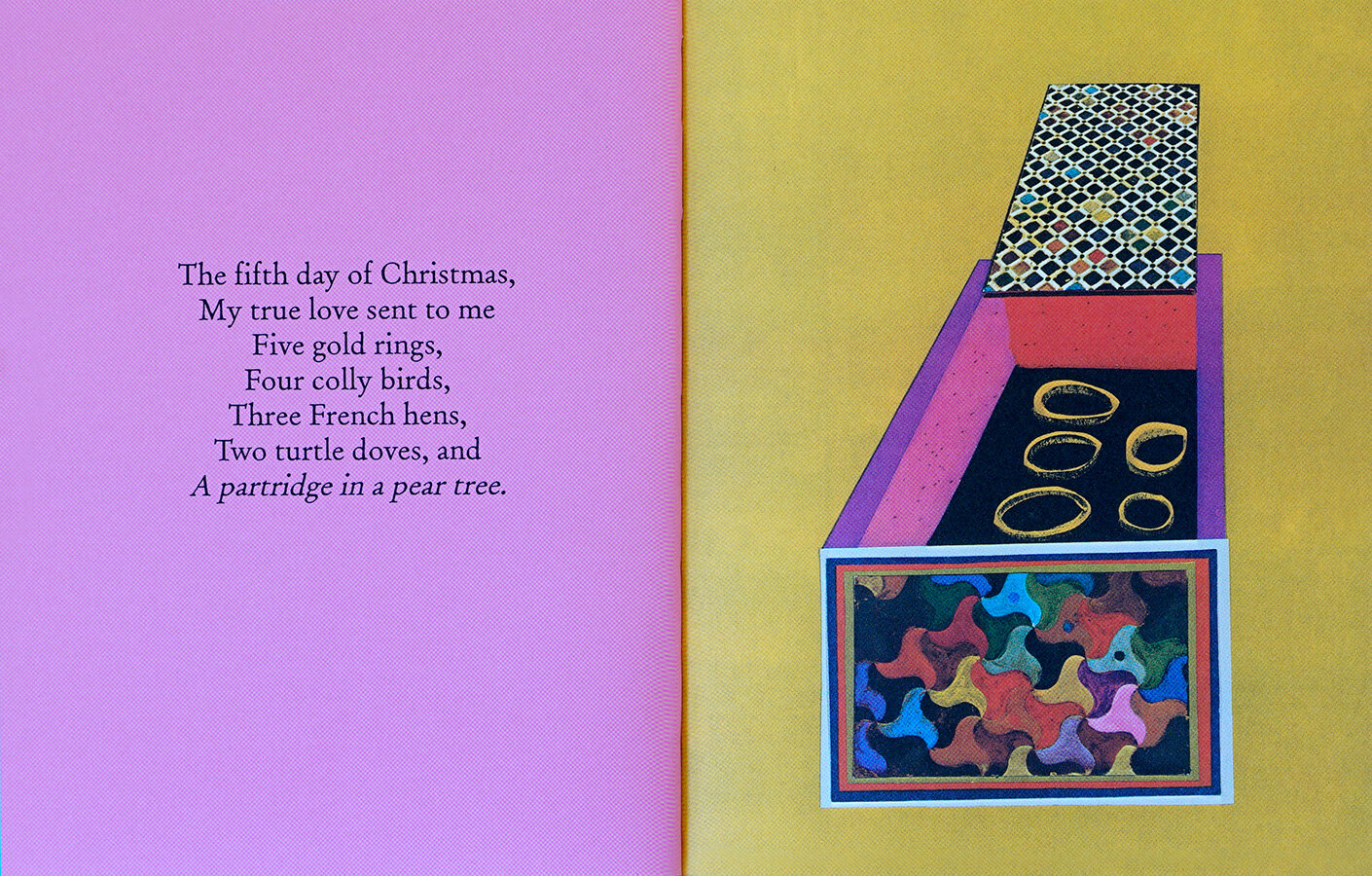

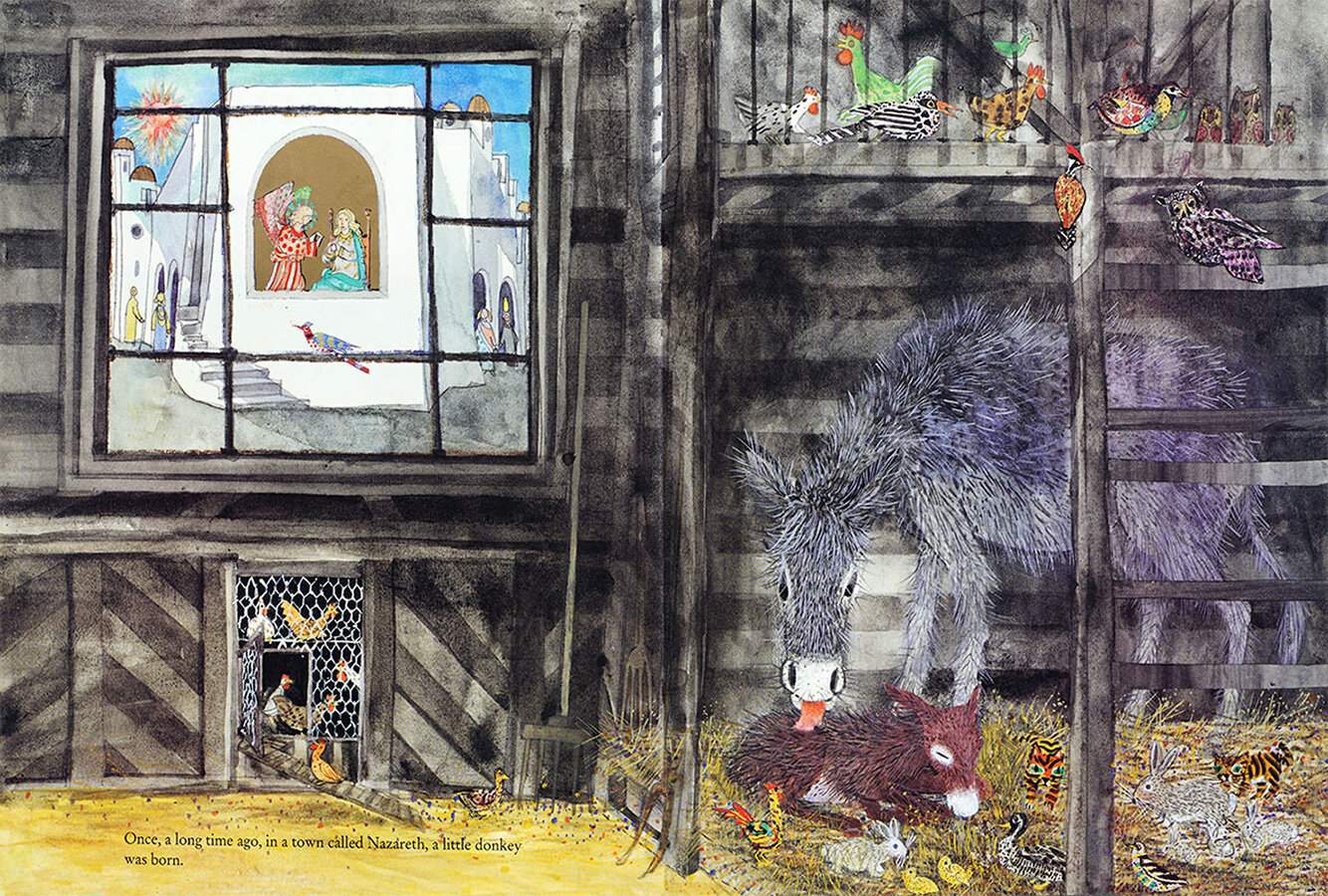

For the next project he had decided to create a book illustrating the gifts offered in the traditional Christmas carol, The Twelve Days of Christmas. When first published in 1972, it was chosen by Sidney Horn, who described it as a “beautiful Christmas book for the season” and included in The Horn Book, a compilation of the best Christmas books from 1960-1972. The author added, “The impression overall is of having been invited to a gallery for a special Christmas exhibition.” Oxford University Press did a wonderful job in 2018 re-printing it in a smaller format with a newly designed, more contemporary cover… A perfect stocking filler!

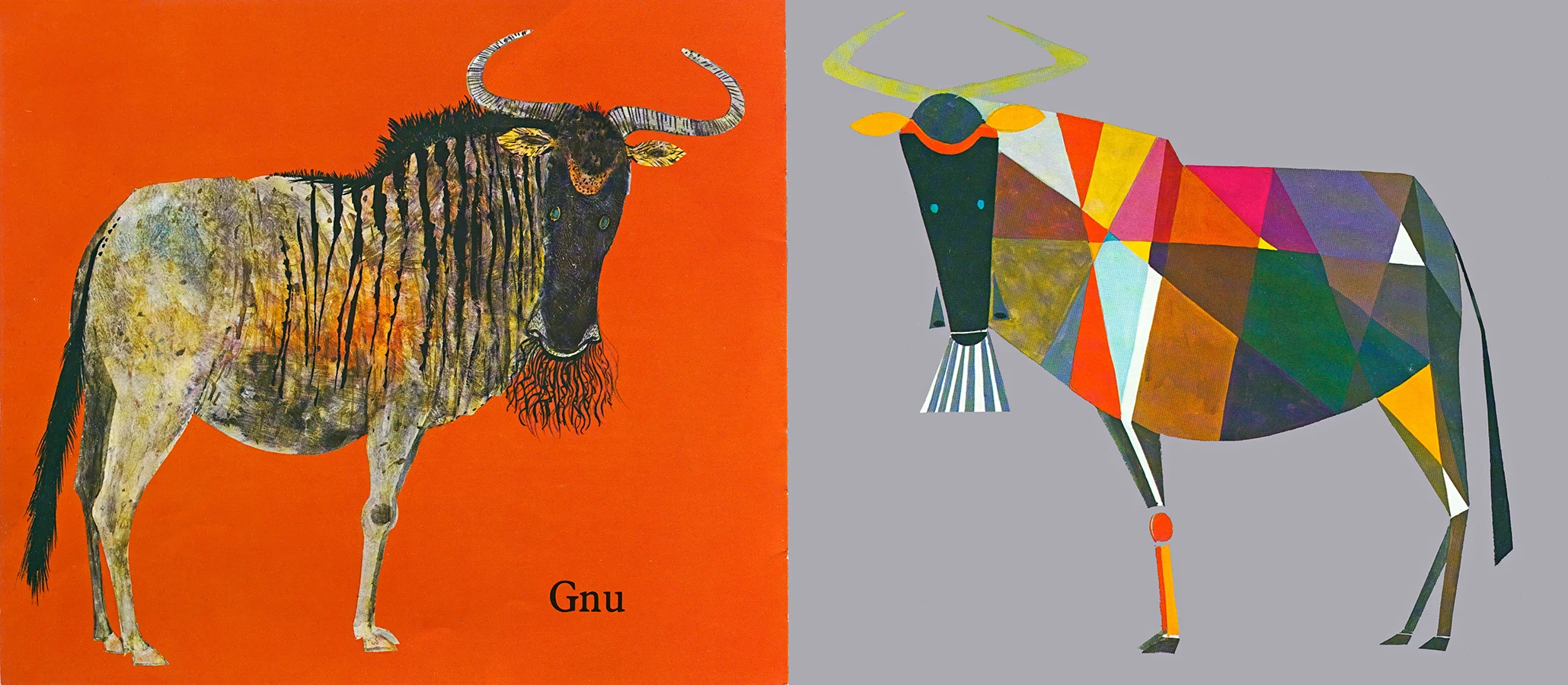

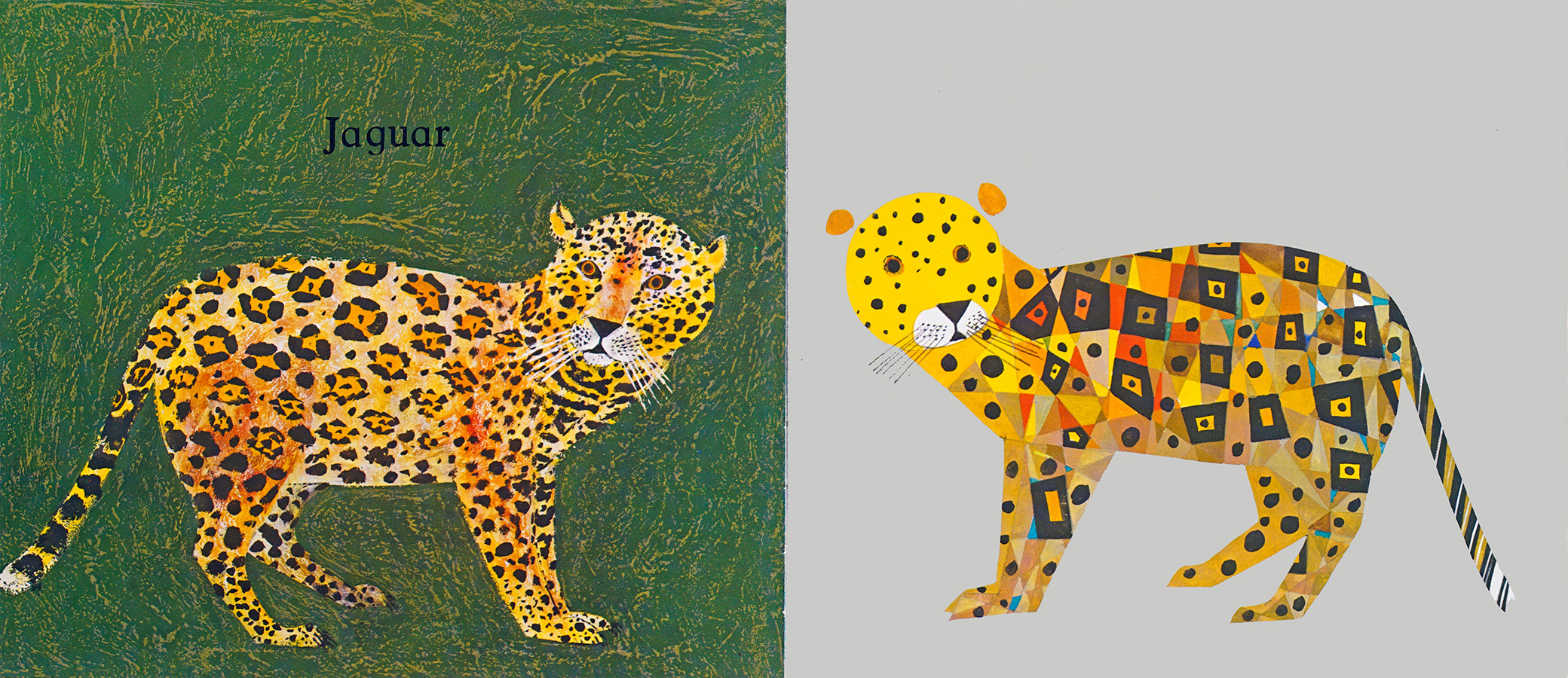

The Twelve Days of Christmas, 1972 and its “geometric designs and brilliant unique, patchworked colors,” The New York Times.

This book was reprinted in 2018 in a beautiful cloth-bound edition as can be seen later in this chapter.

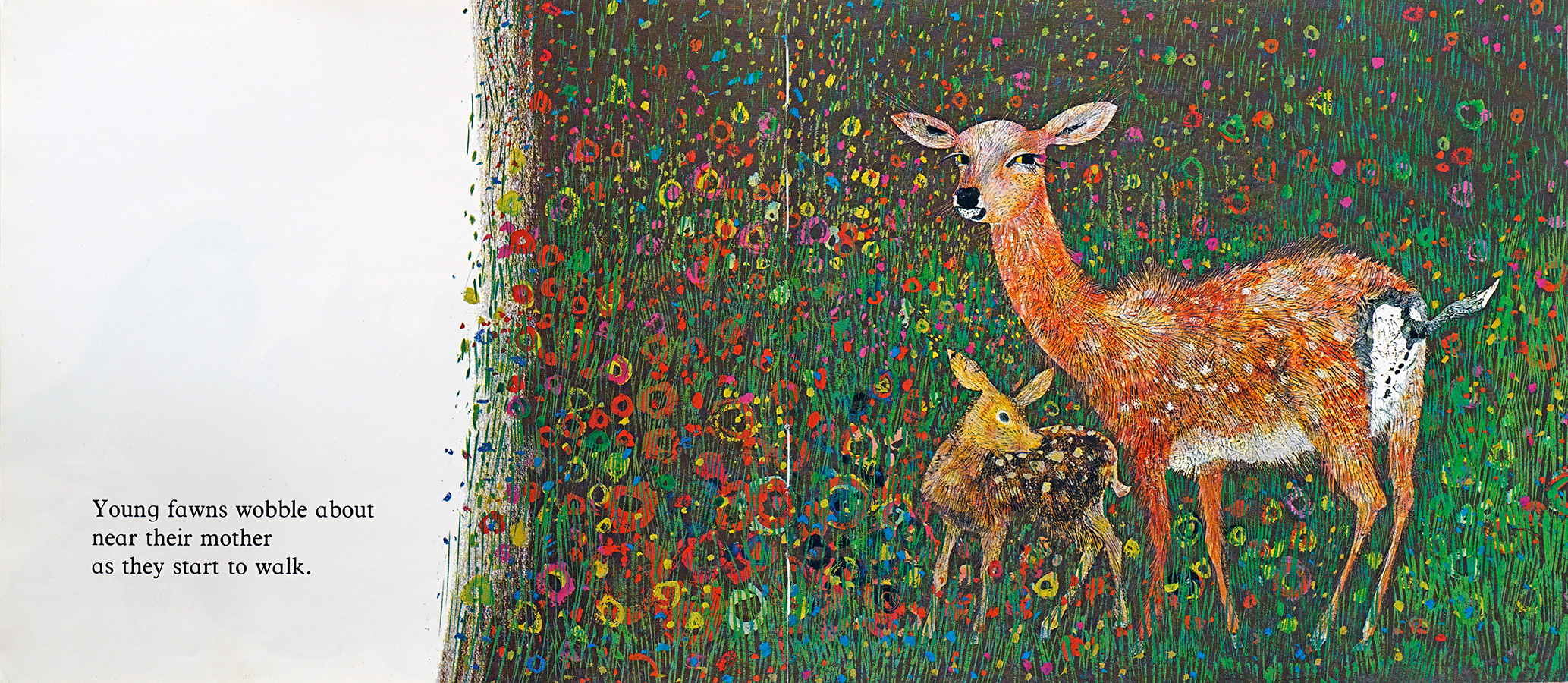

Continuing his dedication to children’s education, enlightenment, and of course, their entertainment, he published both The Little Wood Duck, in 1972, with its “minute attention to detail and gorgeous colour” and The Lazy Bear, 1973, “filled with the brilliant colour which is the artist’s hallmark,” said The Times Literary Supplement. This book has a number of illustrations containing quantities of long, lush and multi-coloured grasses - fabulous graphically, but a decidedly laborious task to paint, so Brian put his two elder daughters to work. The dedication “For Clare and Rebecca who made the grass grow” (image 1 below) is his amusing acknowledgment for this help.

The Lazy Bear, 1973 with its psychedelic vegetation that Clare aged 15 and Rebecca 13 helped paint!

REVENGE FOR AN ADDER’S BITE

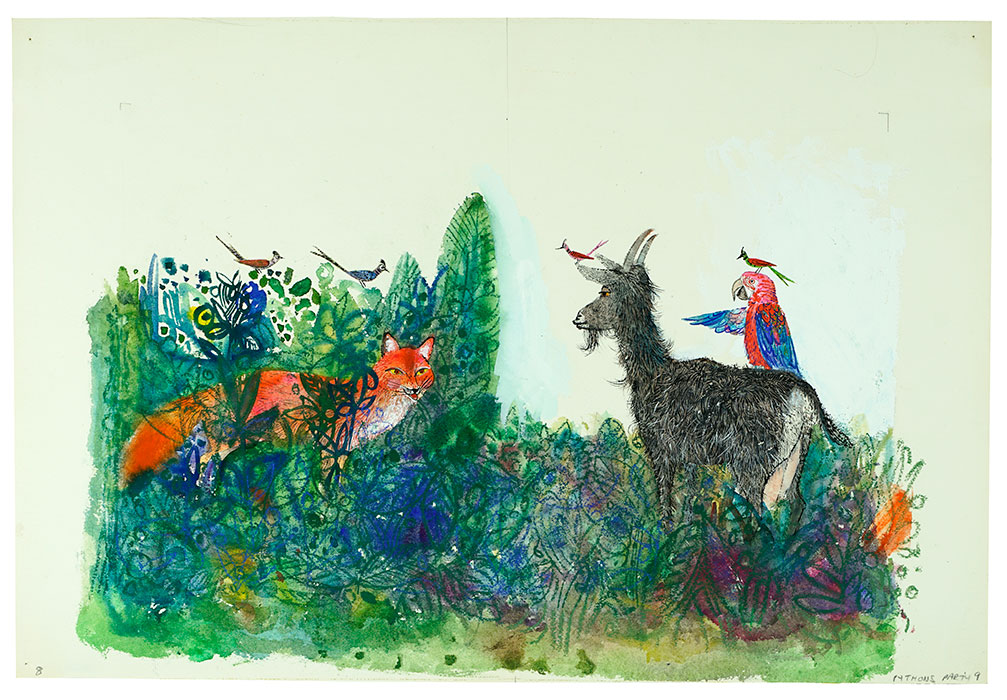

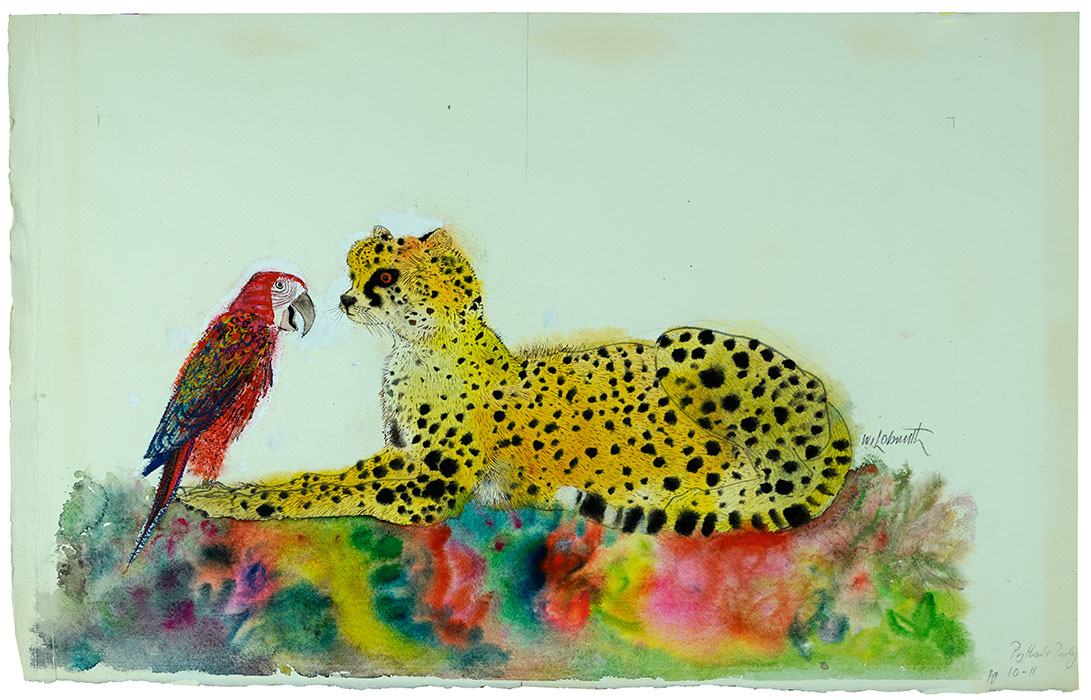

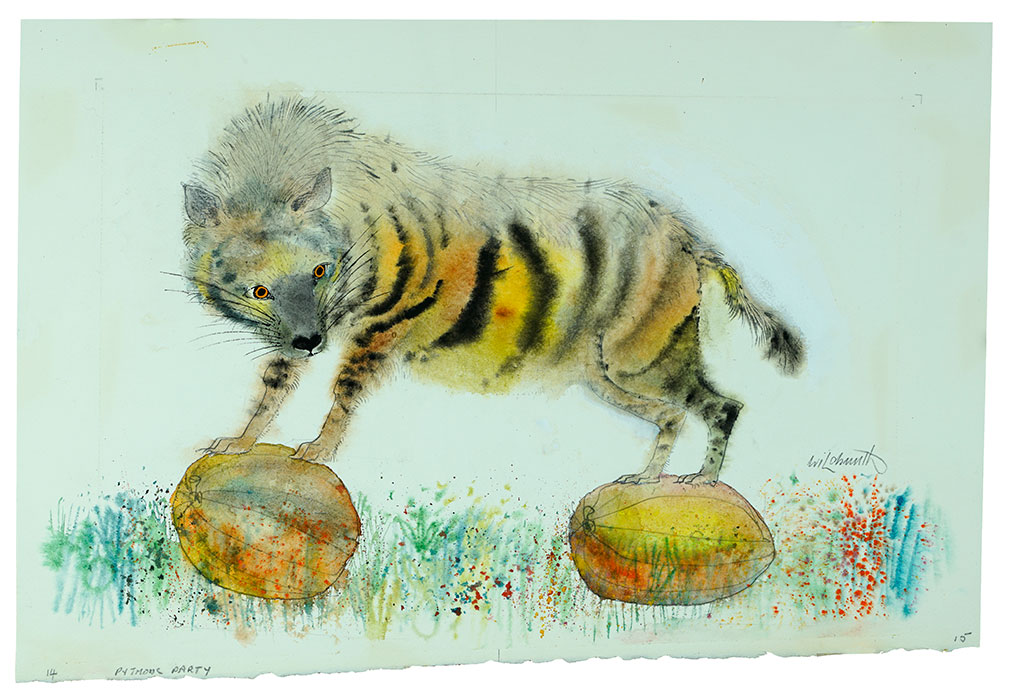

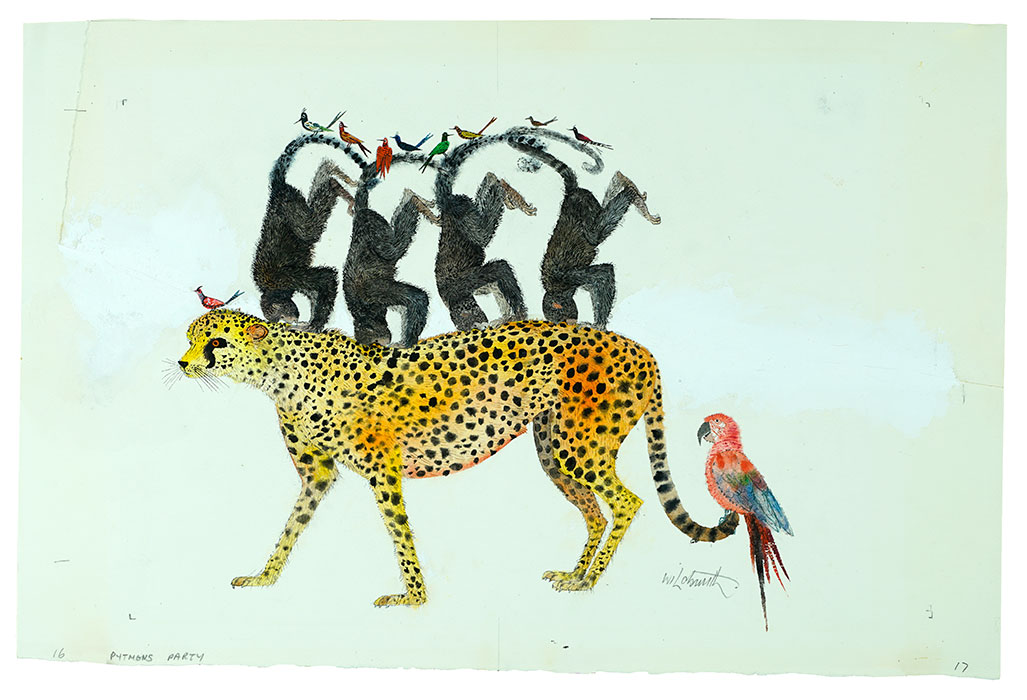

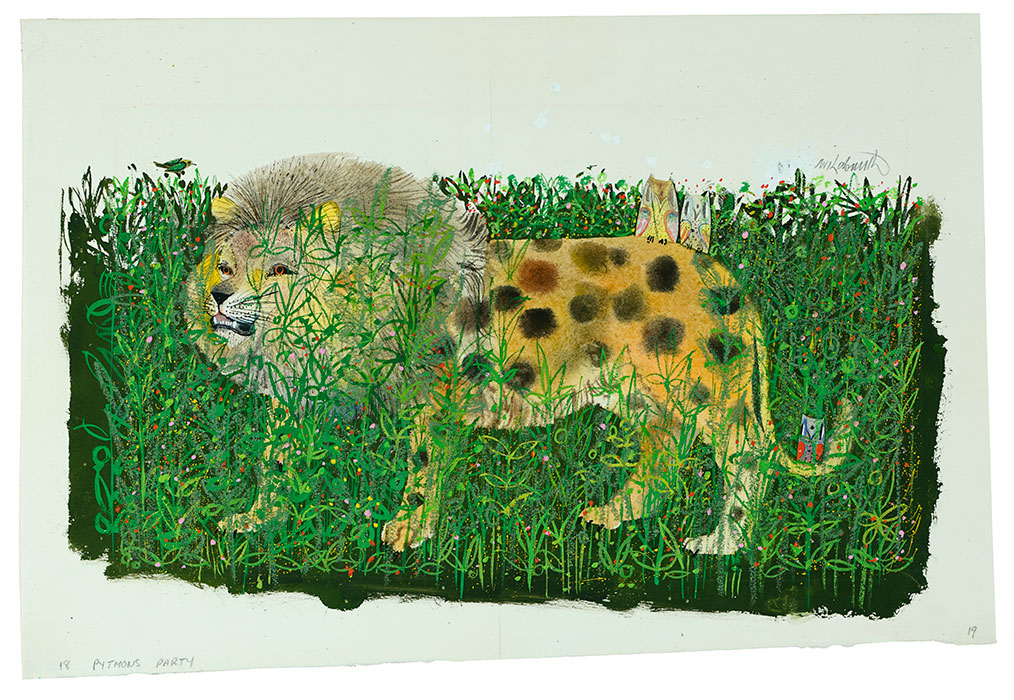

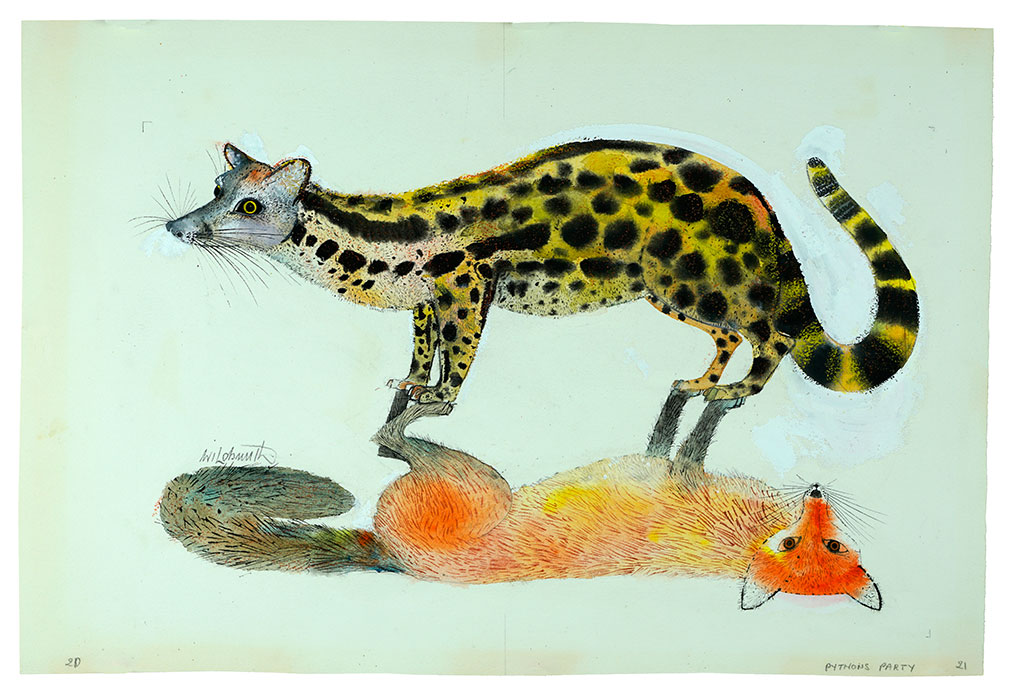

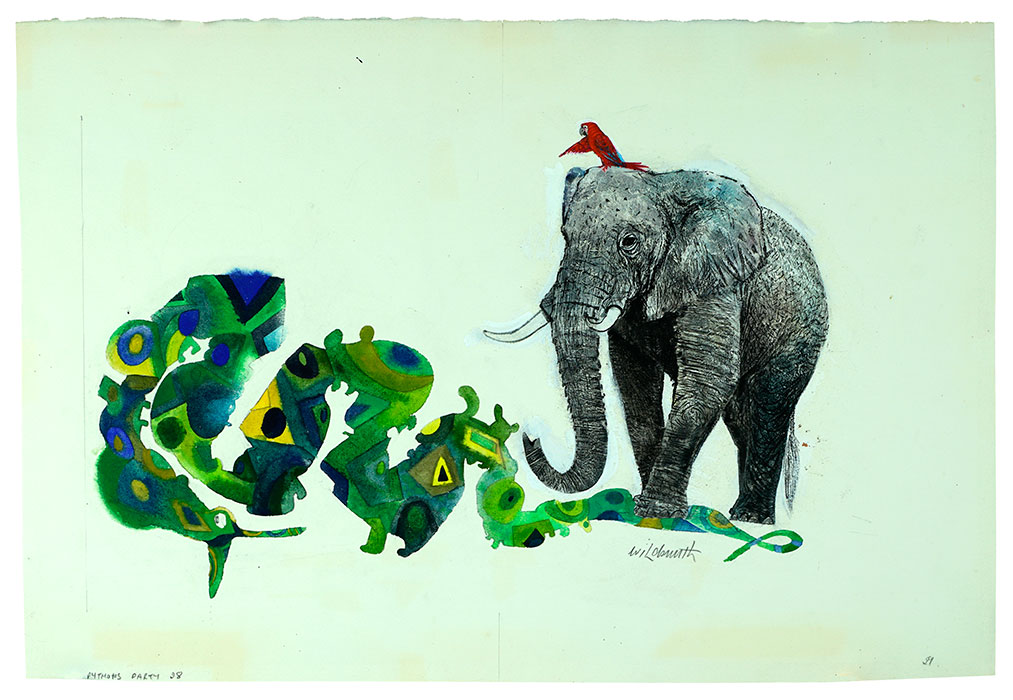

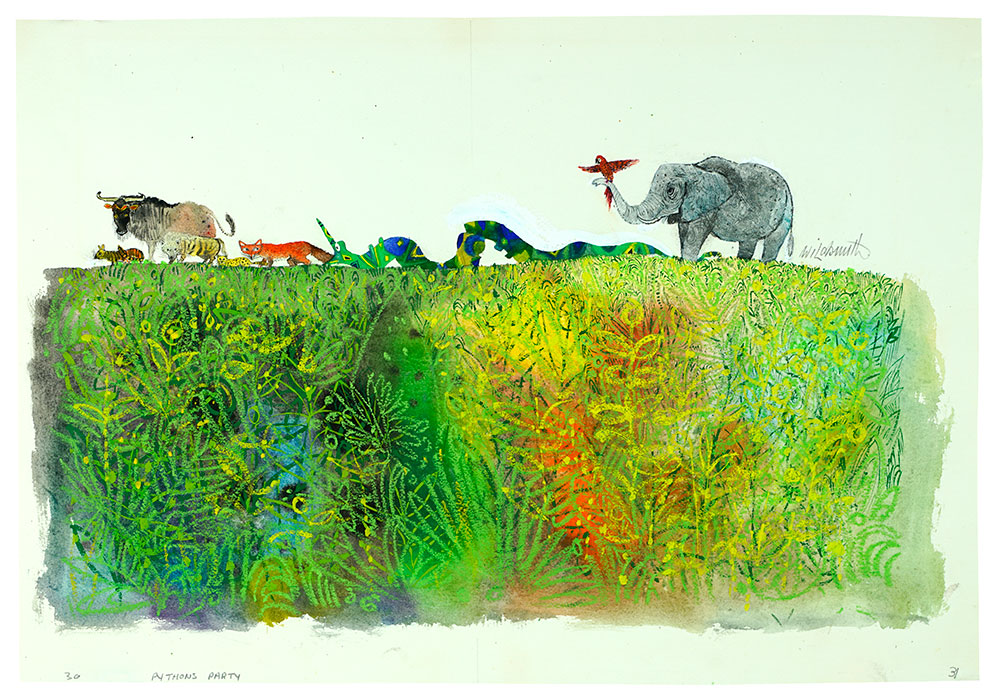

Squirrels, followed in 1974, which has been described as an “exciting experience, moreover a promise for the future of this infinitely talented artist,” and then Python’s Party, now called Jungle Party. These last four titles expressed important concepts he wanted to communicate: fellowship and good neighbourliness, altruism and kindness, all laid out on pages full of aesthetic and fantastical beauty.

The books were wonderfully received with adjectives such as “vibrant,” “opulent,” “dazzling” and “brilliant.” We were reminded very recently, from a telephone interview designed to promote various exhibitions celebrating his 80th birthday and conducted by Alex Fitch (for Panel Borders - The Art of Brian Wildsmith) that there is a poisonous story behind the creation of Jungle Party. Brian was out in his back garden on a sunny summer’s day tending his tomatoes, when suddenly he felt something bite his ankle. He saw no culprit and imagined it must have been a bee. However, upon returning to the kitchen to investigate the area of pain more closely, he discovered two fang bites in the centre of one hell of a swelling. He had, in fact, been bitten by an adder! His liberation from the poison, he believed, was achieved with a venom extractor, while the psychological trauma was evacuated with creative revenge and the quite surreal and beautiful Jungle Party.

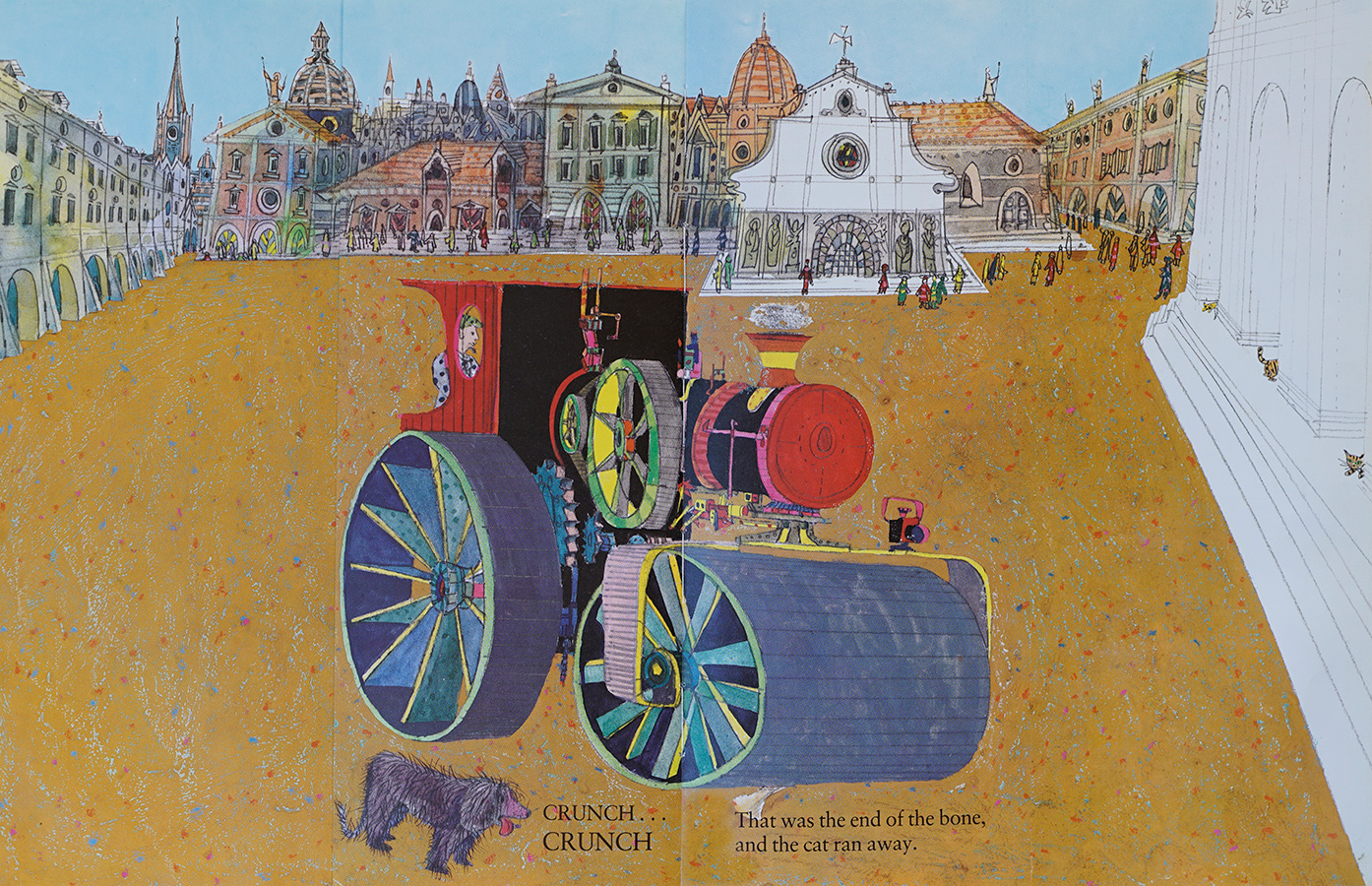

Original illustrations from Python’s Party, 1974, now titled Jungle Party, a tale that allowed Brian to evacuate the trauma caused by an adder’s bite!

The BLUE BIRD film

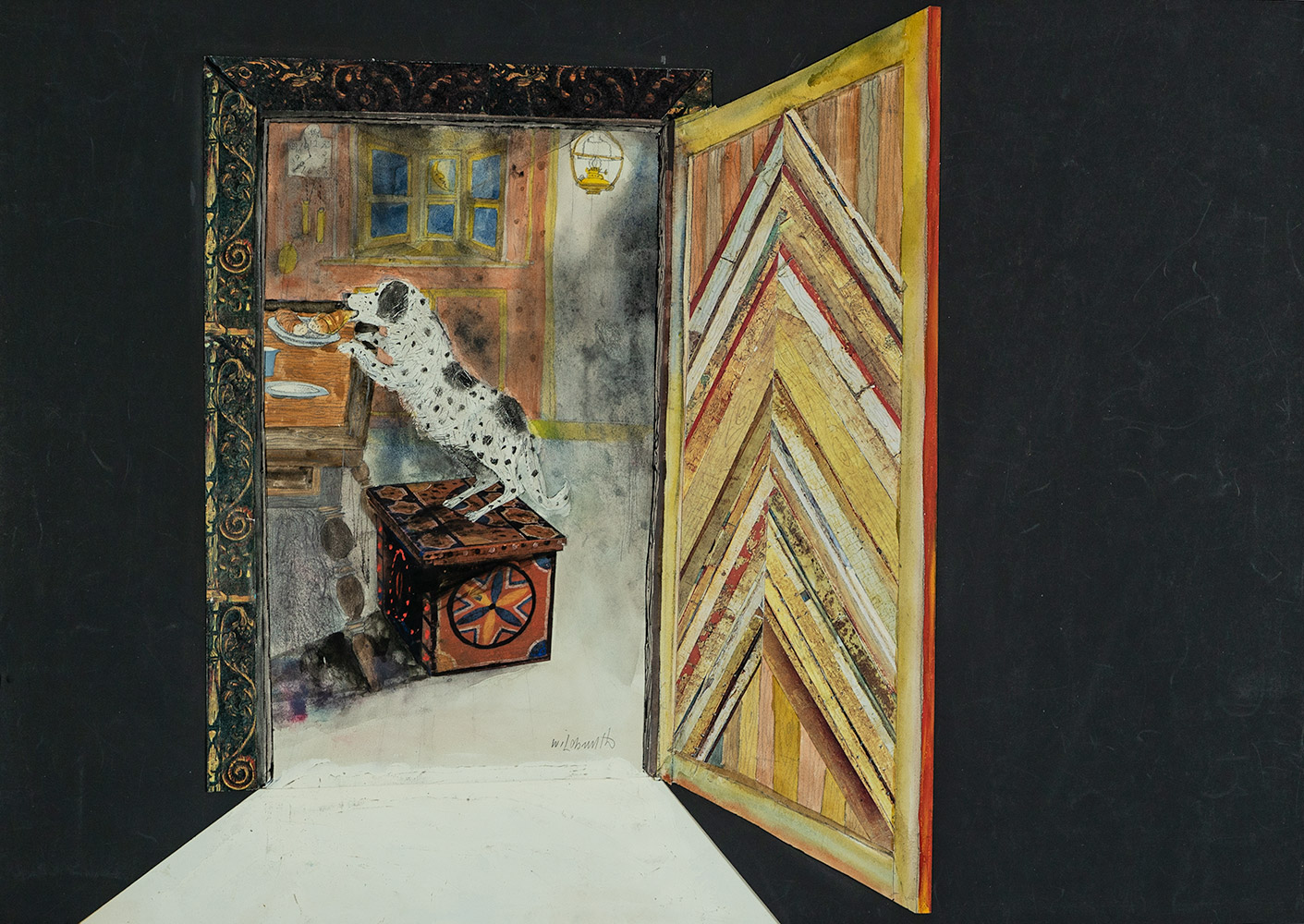

Film set scene. Ink drawing from The Knights of King Midas, 1961.

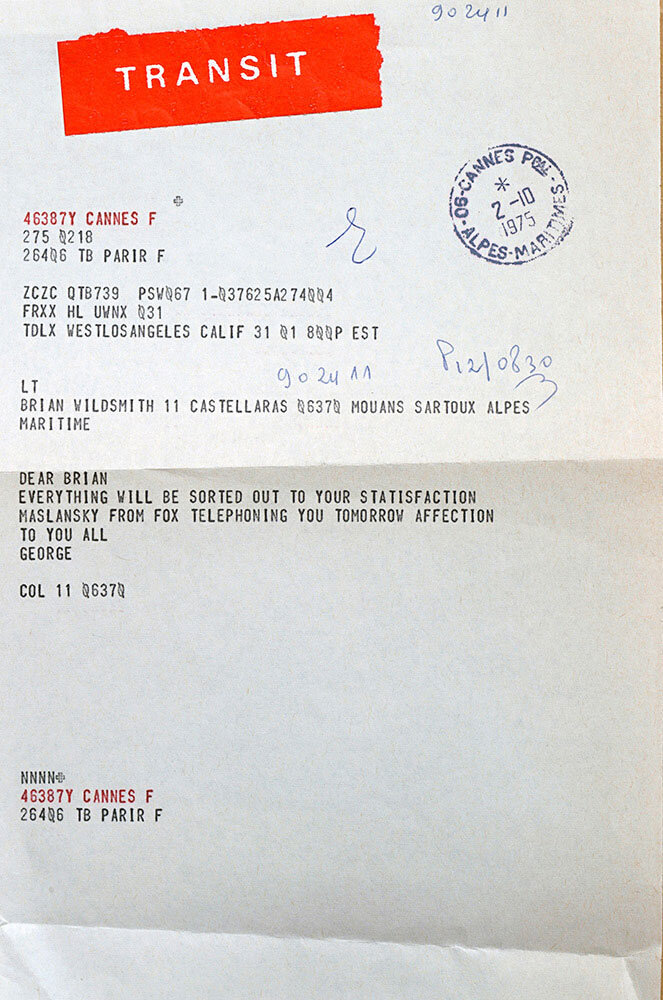

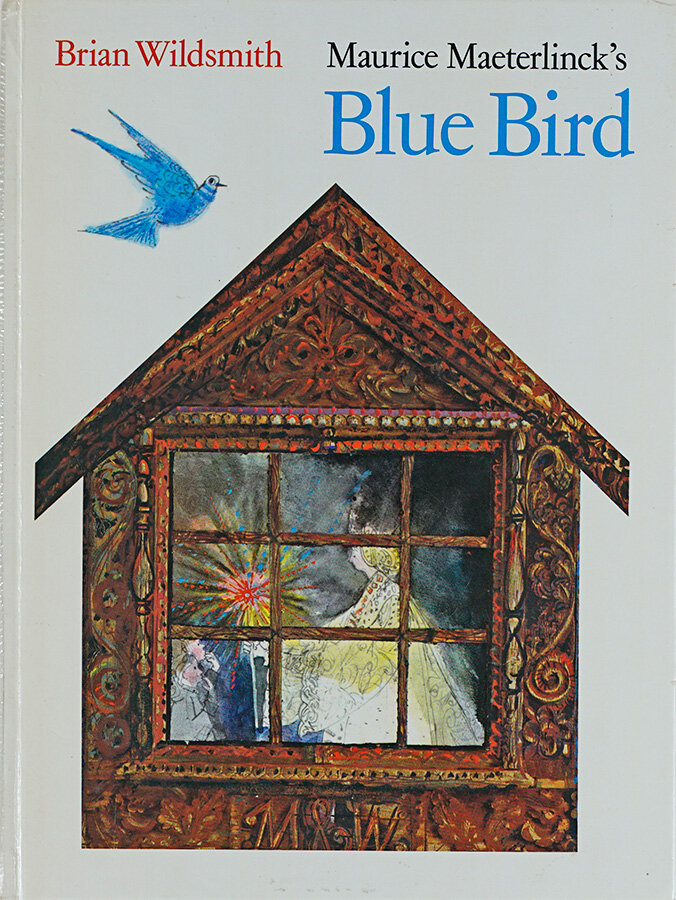

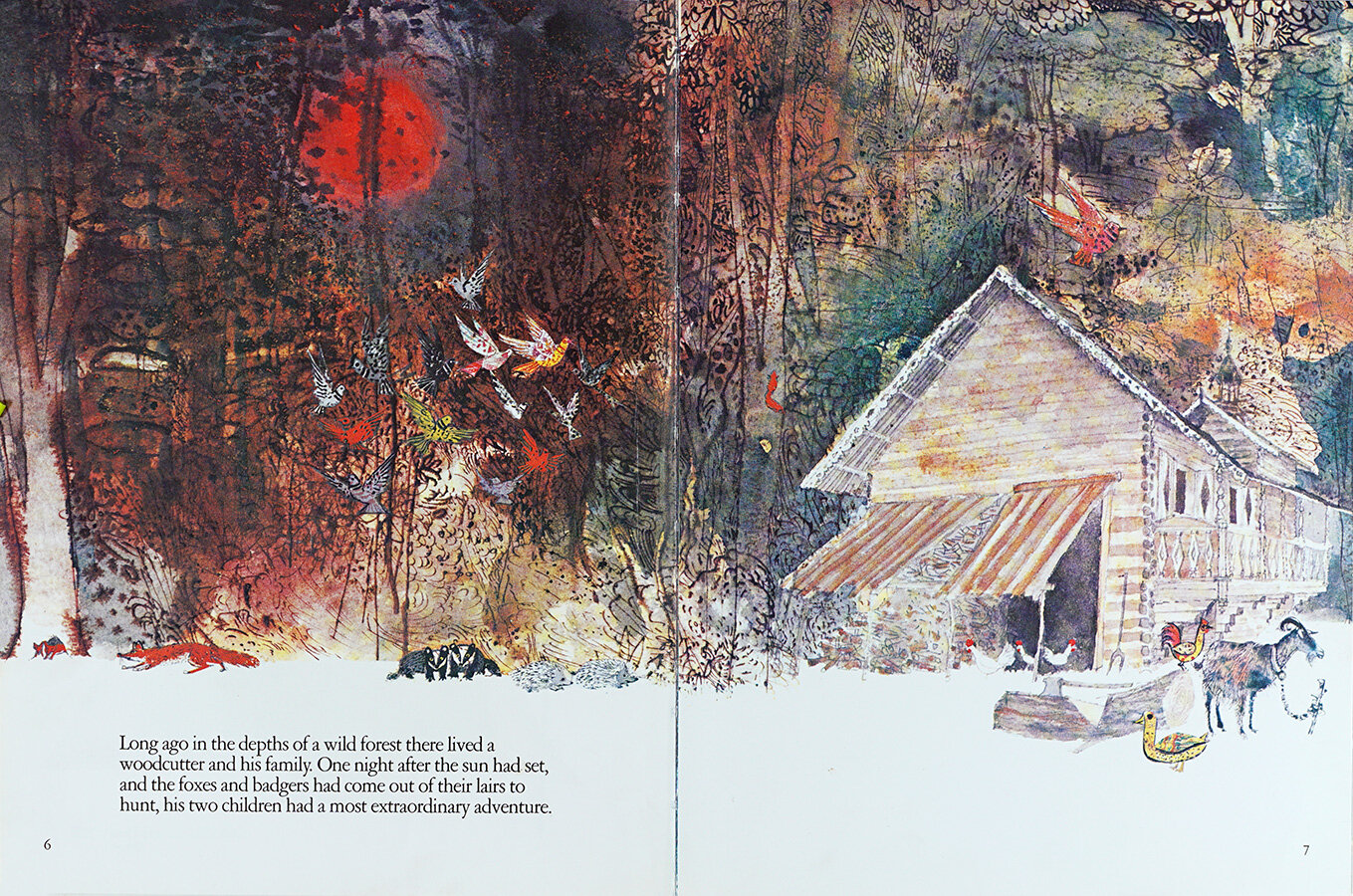

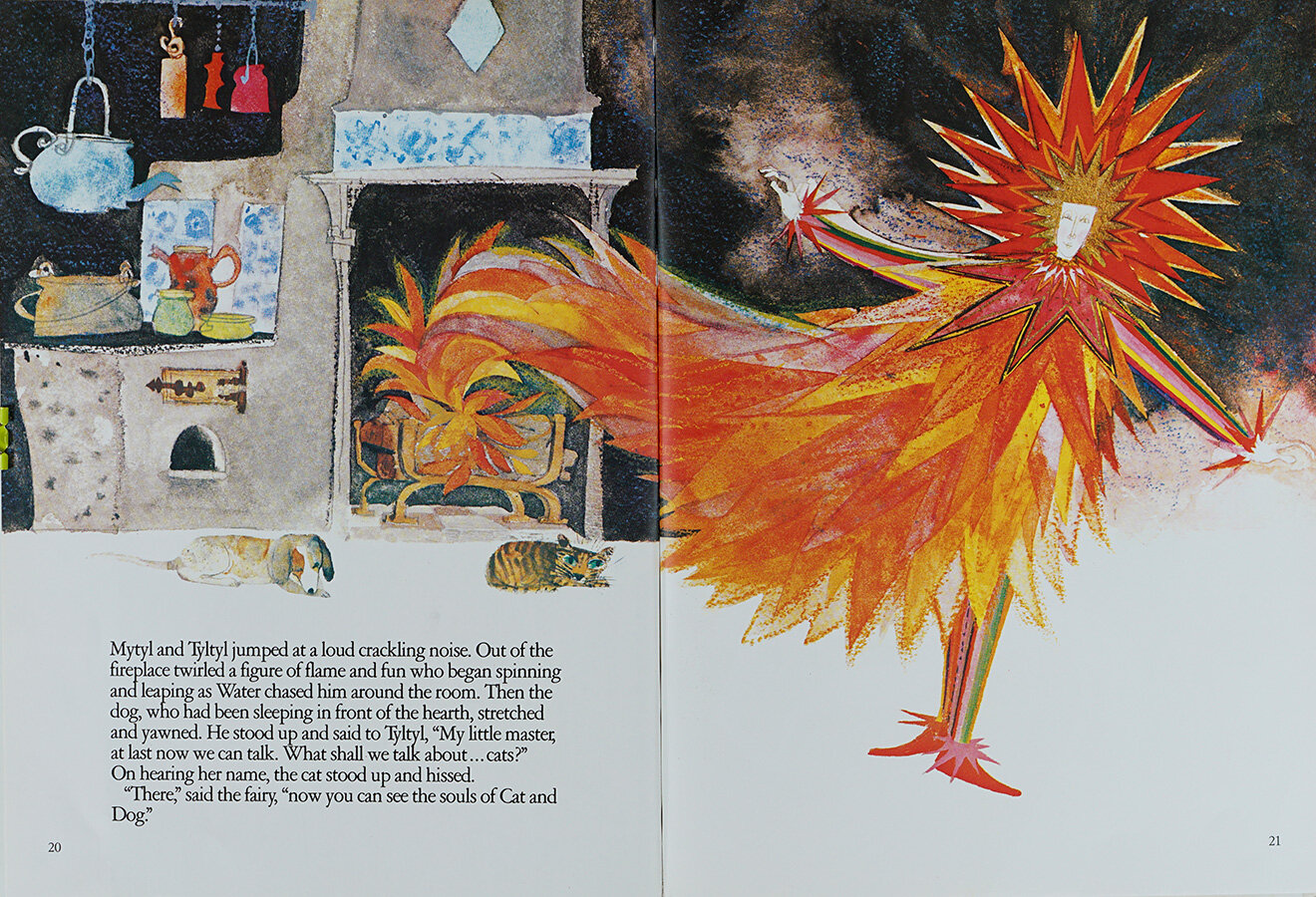

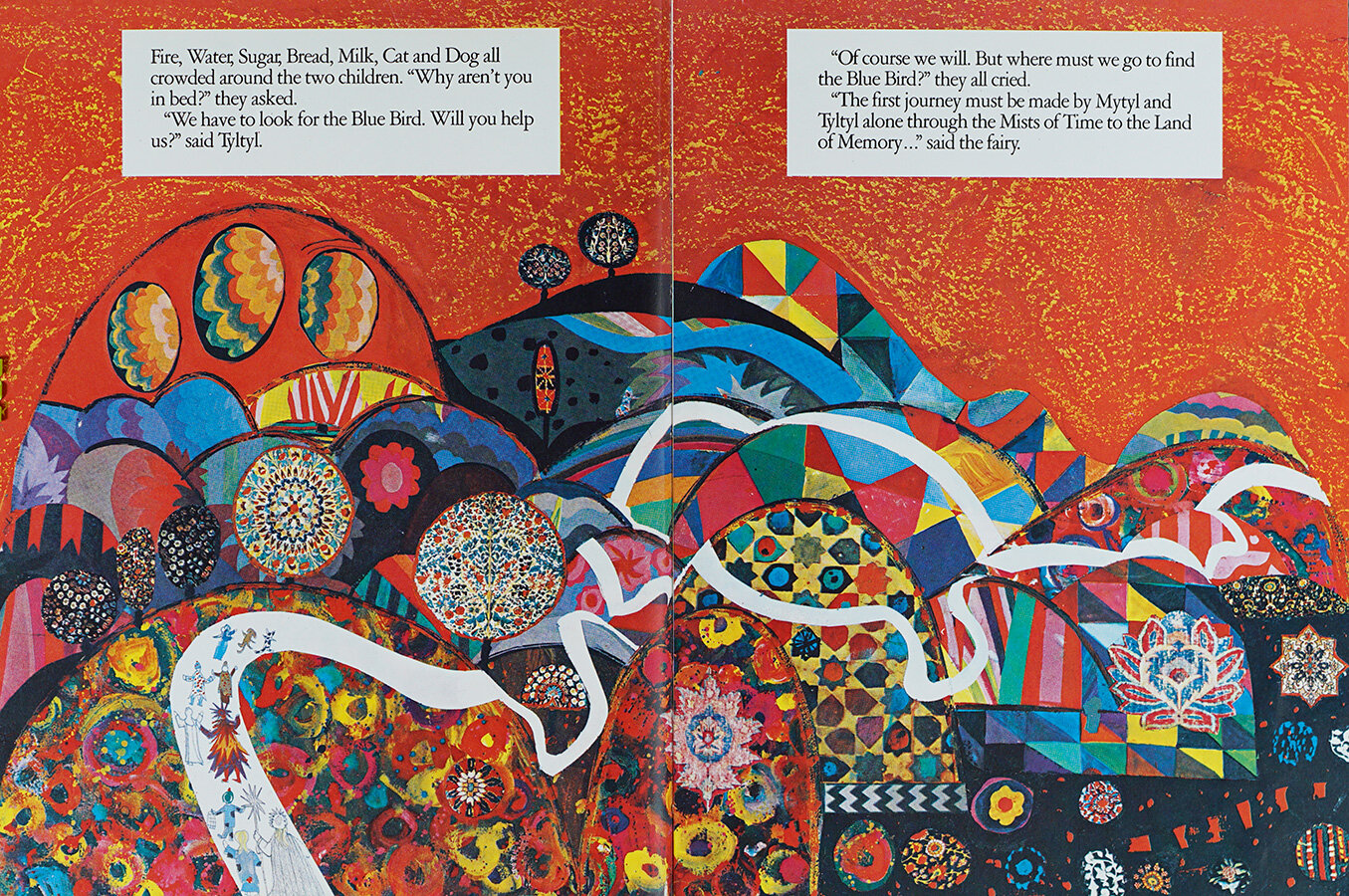

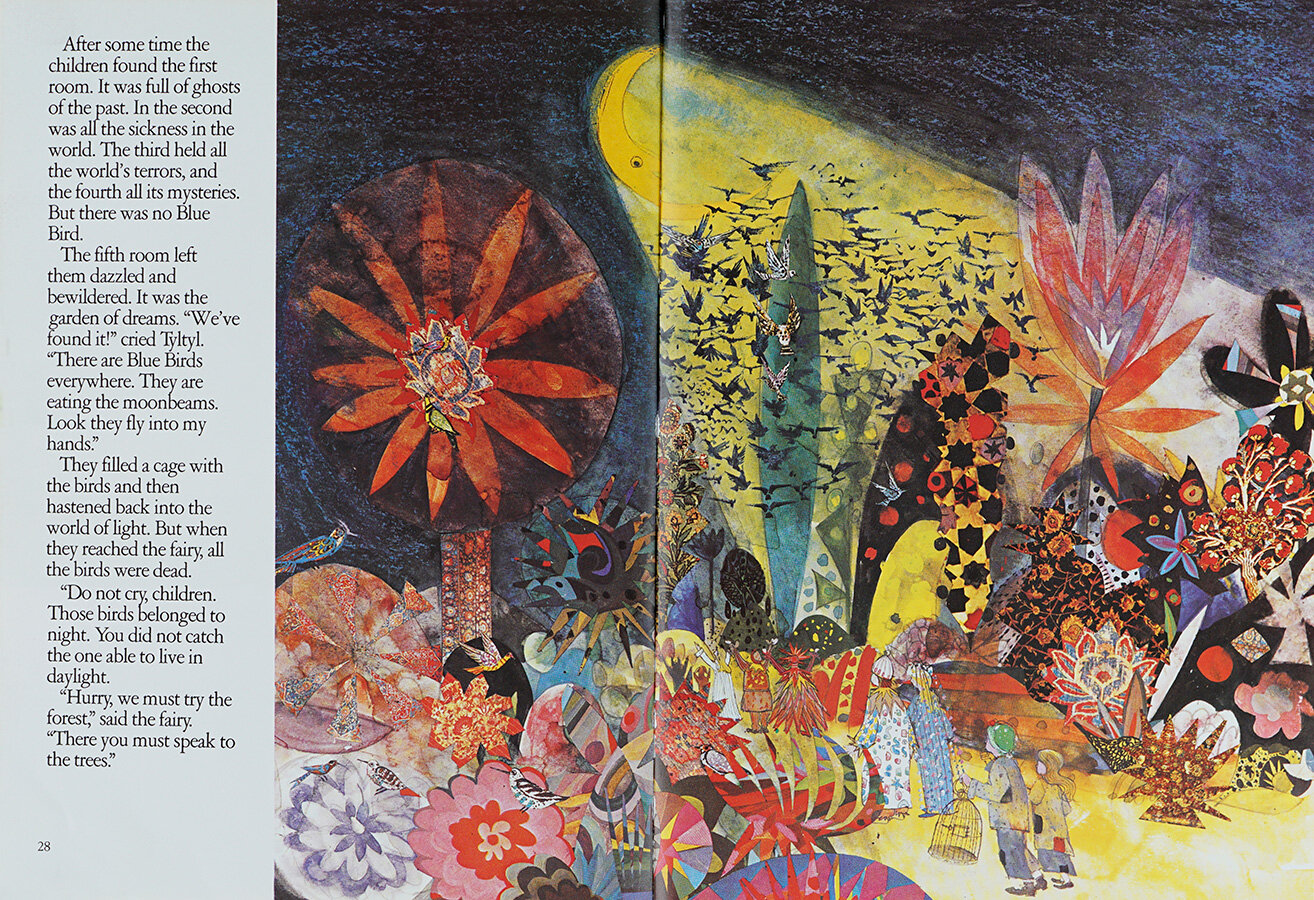

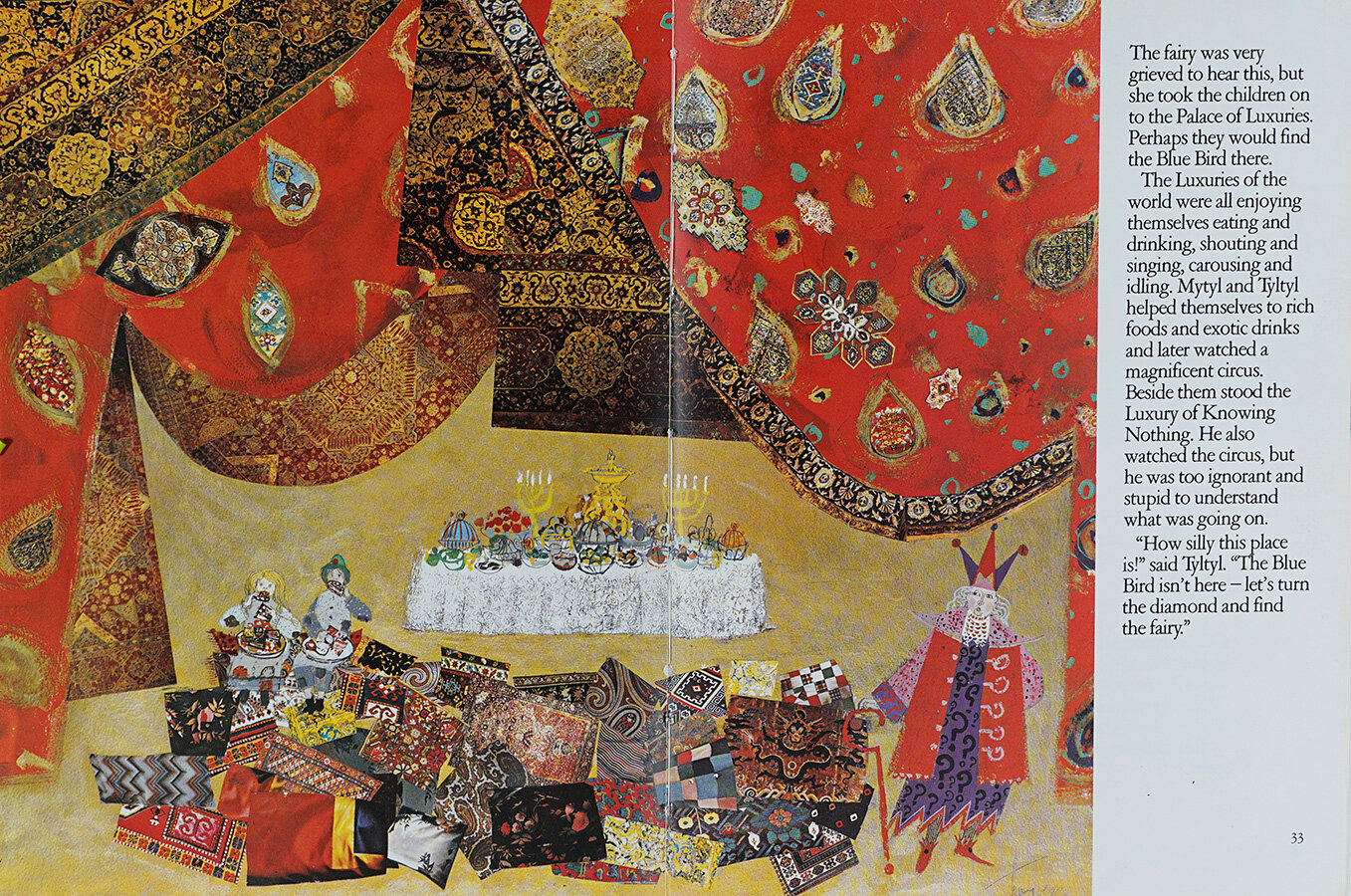

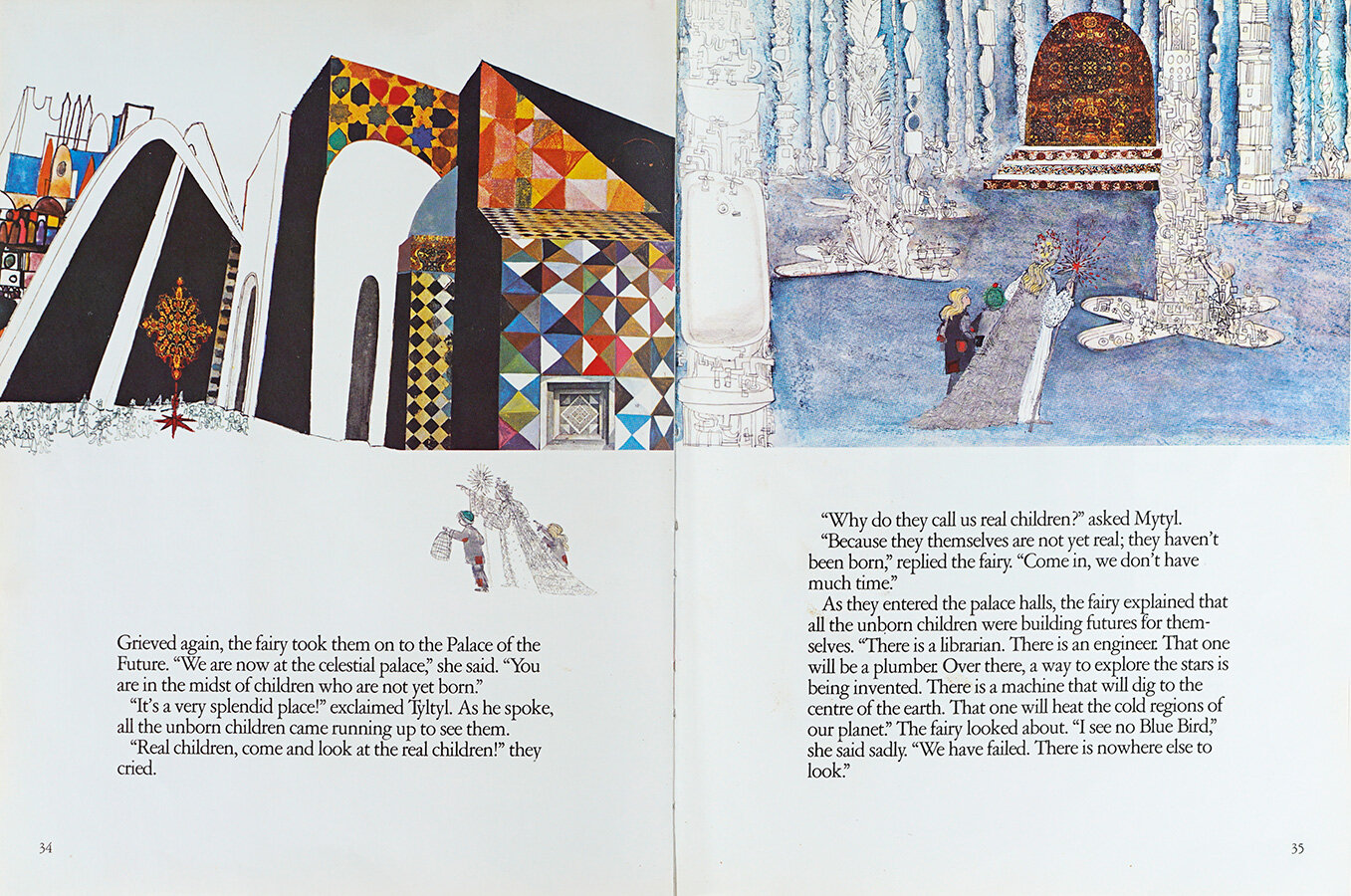

In 1974, just before her retirement and after a meeting with Brian, Mabel George, who had been awarded an MBE six years earlier for her “editorial achievements,” as well as her “outstanding contribution to children’s literature,” wrote: “There he sits across the café table, his face alight with enthusiasm, his fingers searching in his pocket for pencil and paper. He has just been commissioned to design sets and costumes for what should be a spectacular musical film that promises to make the Christmas of 1976 an unforgettable one for millions of children.” Maurice Maeterlinck’s Blue Bird, the first USA/USSR co-production, was to be filmed in Leningrad, directed by George Cukor. (The Philadelphia Story, Gaslight, My Fair Lady, Little Women…)

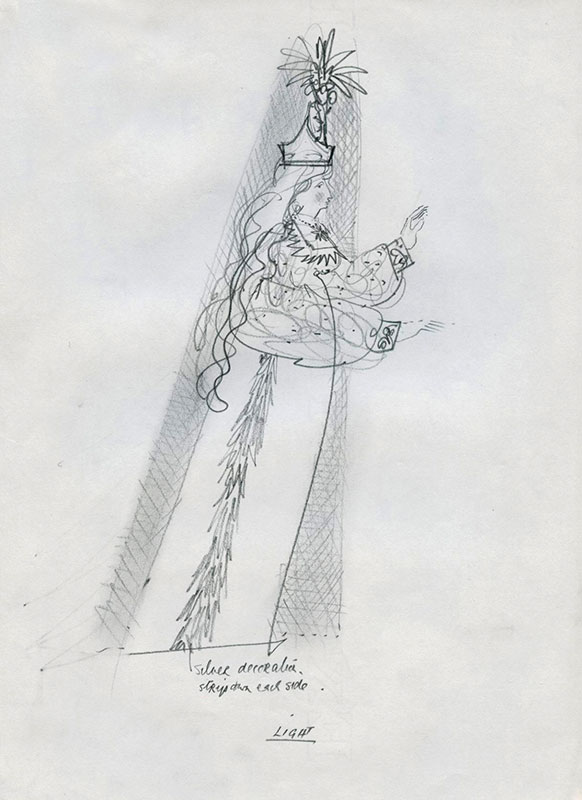

“I was full of excitement,” said Brian, “as I landed for the first time in Leningrad, the wondrous city, now impatient to discover its palaces, the Hermitage museum and it’s incredible collection of impressionist paintings and the most glorious Rembrandts I had ever seen. And what to say of the the Kirov ballet whose performances I was so delighted to see. To begin with, I was quite taken by the Russians I met in the course of my work there. It wasn’t long however, before I was to be exposed to their legendary bureaucracy that annoyed me so profusely. My contract and visa, fortunately, allowed me to go back and forth relatively freely so that I didn’t have to stay permanently. I would work on designs at home: over one hundred and twenty costumes, as well as a multitude of sets and then, once a month, go back to Russia to oversee their making or building.

”It became a painful experience though, because amongst a morass of misunderstanding, pettiness, political complexities and an alternation of lavishness and parsimony, the output was a most mediocre film. An example that comes to mind is this: I conceived a set for the Palace of Night - this extraordinary palace on a cloud - and $500,000 (2,4m of today’s money) was spent in making this one set. After all the scenes with it had been shot, it was destroyed to make room for another, but one of the main actors fell seriously ill and had to be replaced. All the scenes in which the previous actor appeared had to be done again. There was no way they could spend another $500,000, so they spent $50, and it looks like it! Disaster followed disaster in this way. At the end it proved a flawed and mediocre film.I was so disappointed with the outcome of my designs for the film, that I decided to publish them in 1976 in a book of the same name.”

Of Blue Bird, The New Observer wrote: “There have never been pictures like this, not even by this talented artist. The colours, the designs and the miraculous visual conception of the storyline are a wonder for the eyes and mind.”

A selection of photographs, press articles and correspondence concerning the Blue Bird film, 1974 - 1975

A selection of roughs and final artwork for sets and costumes Brian designed for the Blue Bird film in 1974 & 1975.

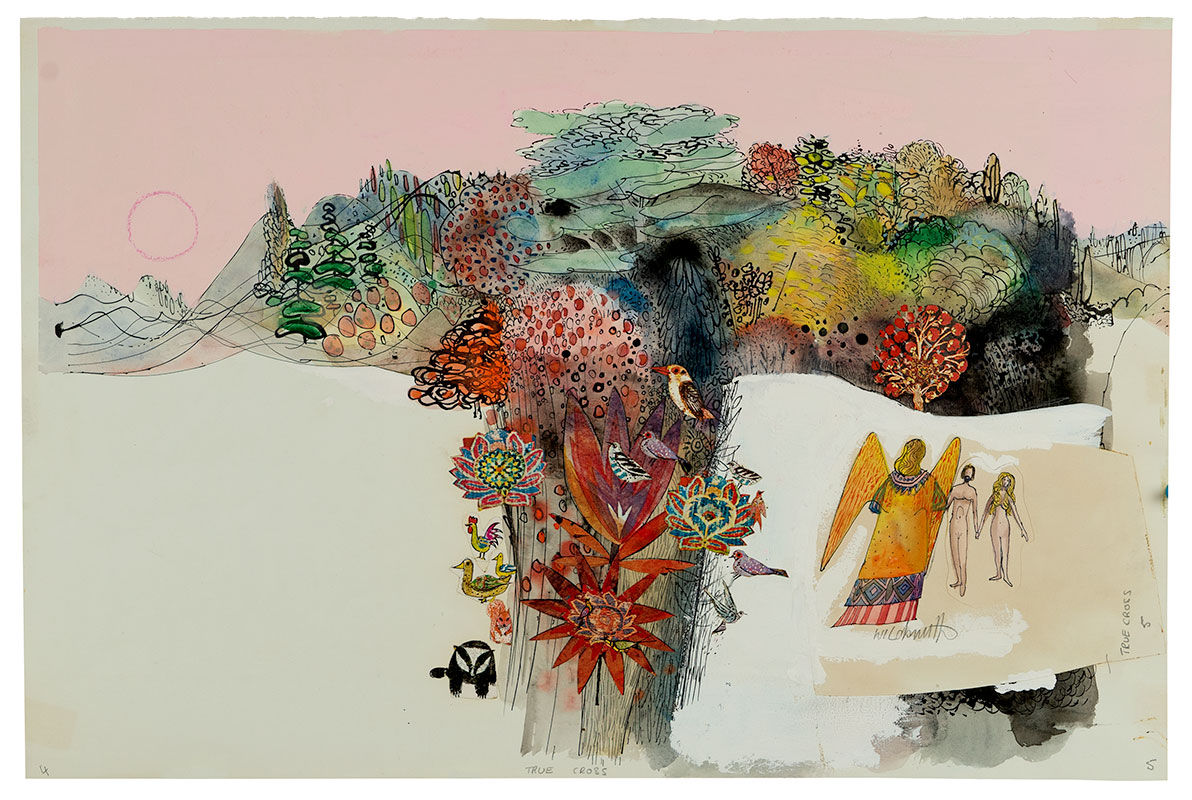

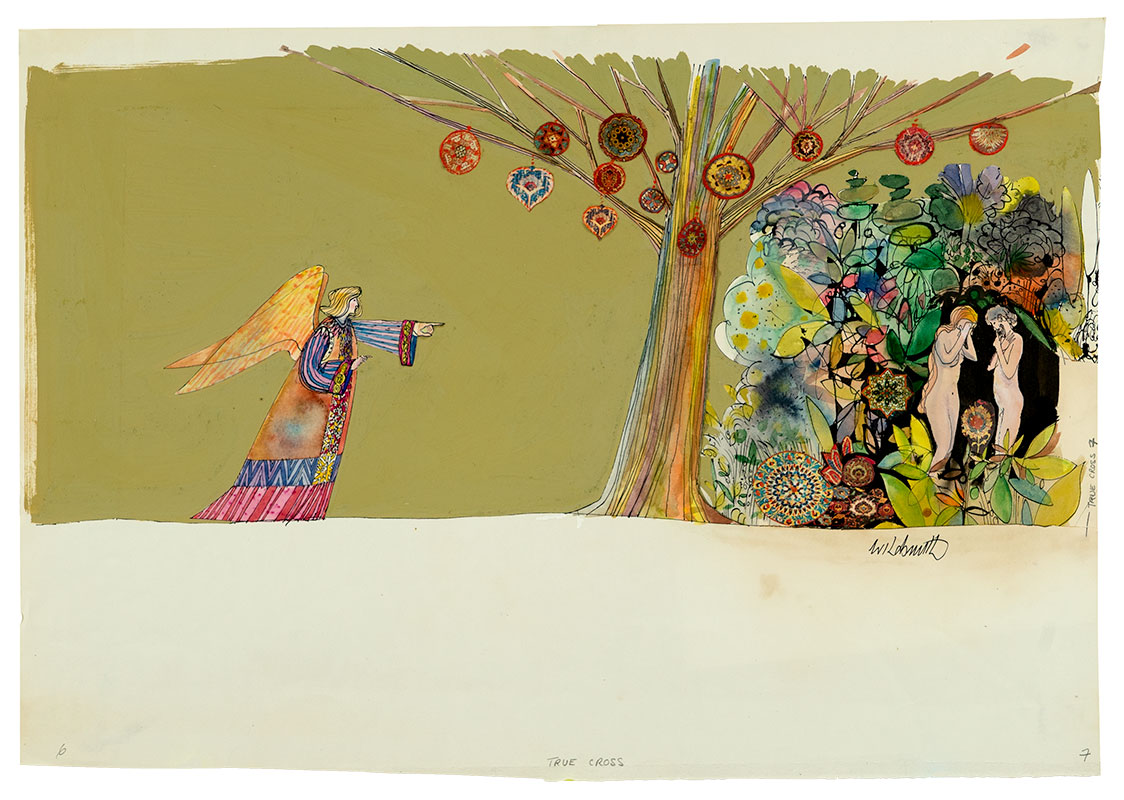

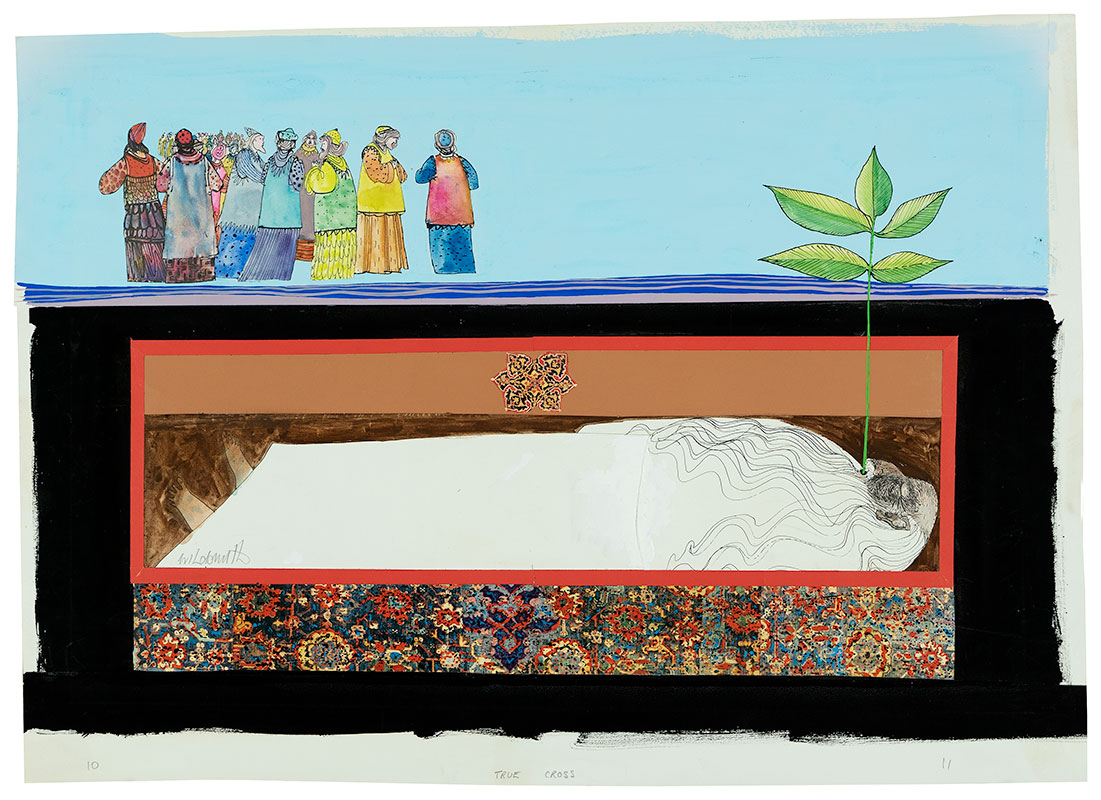

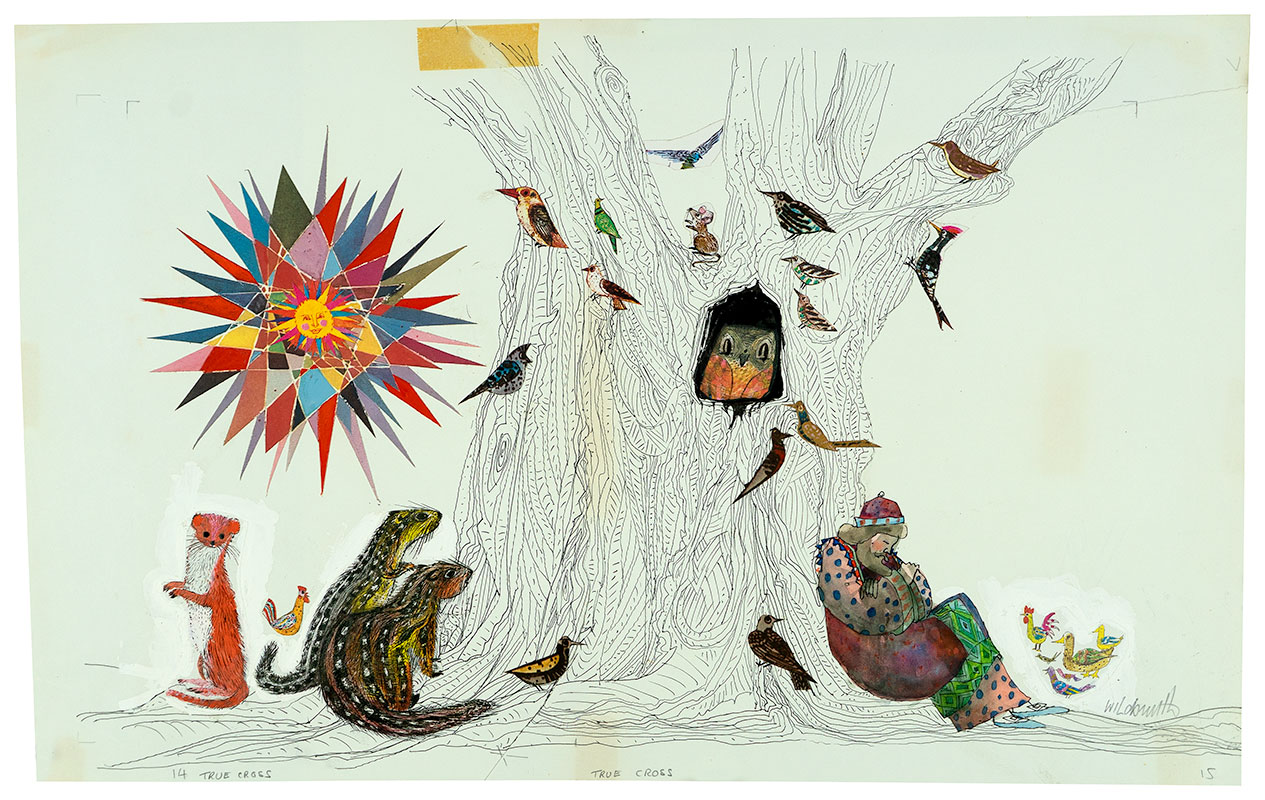

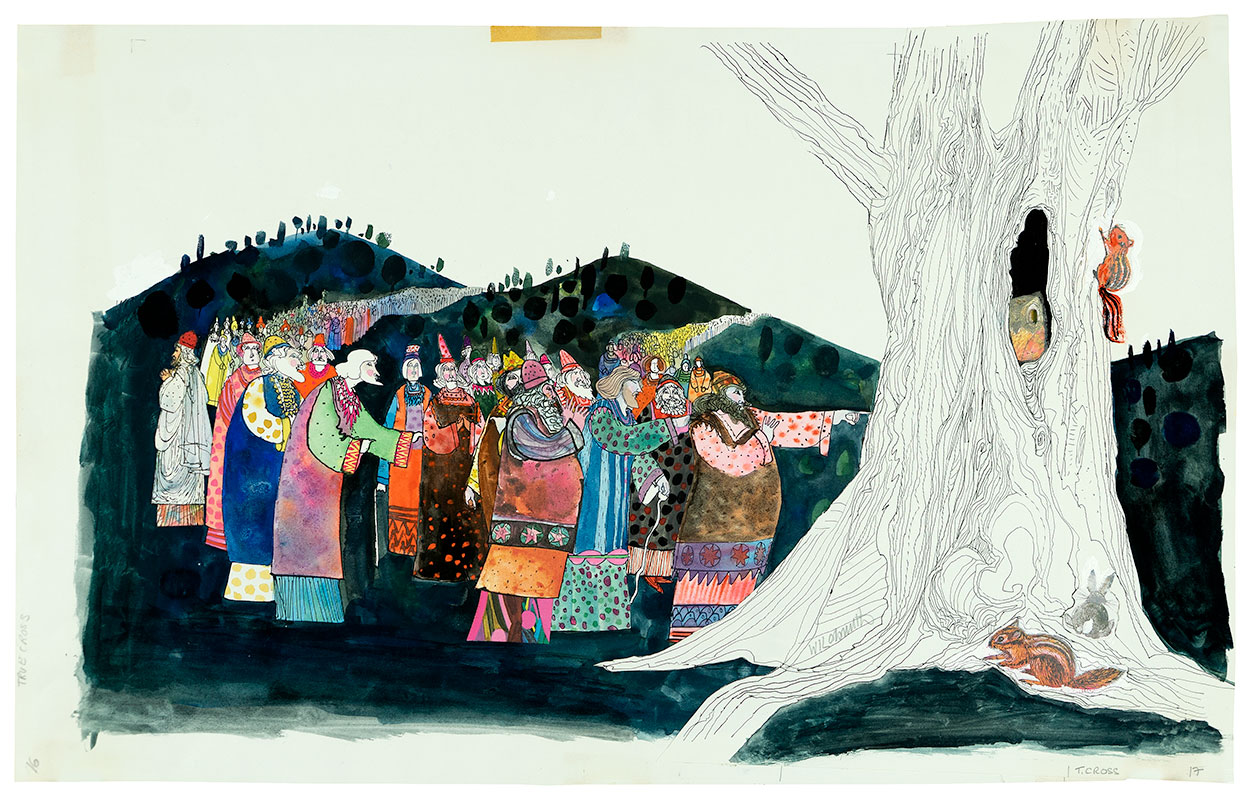

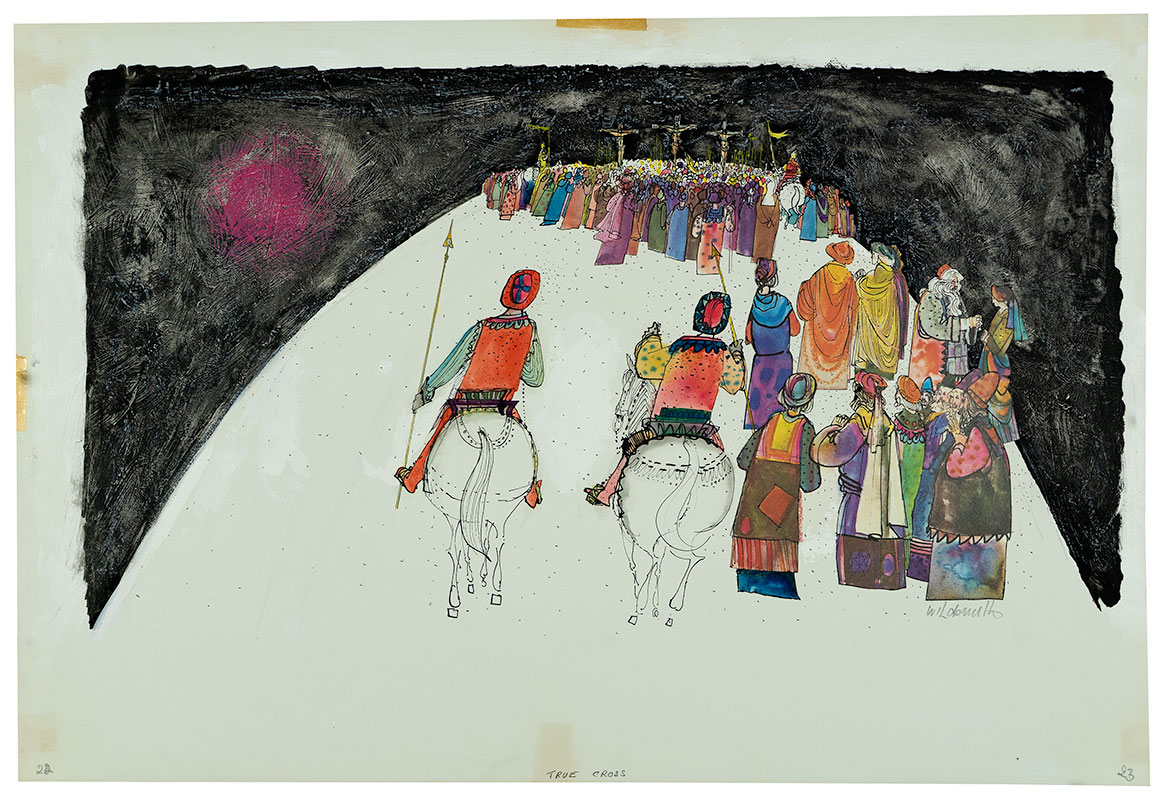

“The Blue Bird project had interrupted my work as a children's illustrator,” commented Brian, “and apart from this title, I had not produced a book for two years. A recent trip to Arezzo in Italy, where the Basilica di San Francesco contains one of my favourite sets of frescoes: Piero della Francesca’s miraculous interpretations of the story of The True Cross, struck up a new idea : my own version of the legend which was published in 1977.”

AN EXPERIENCE IN ART

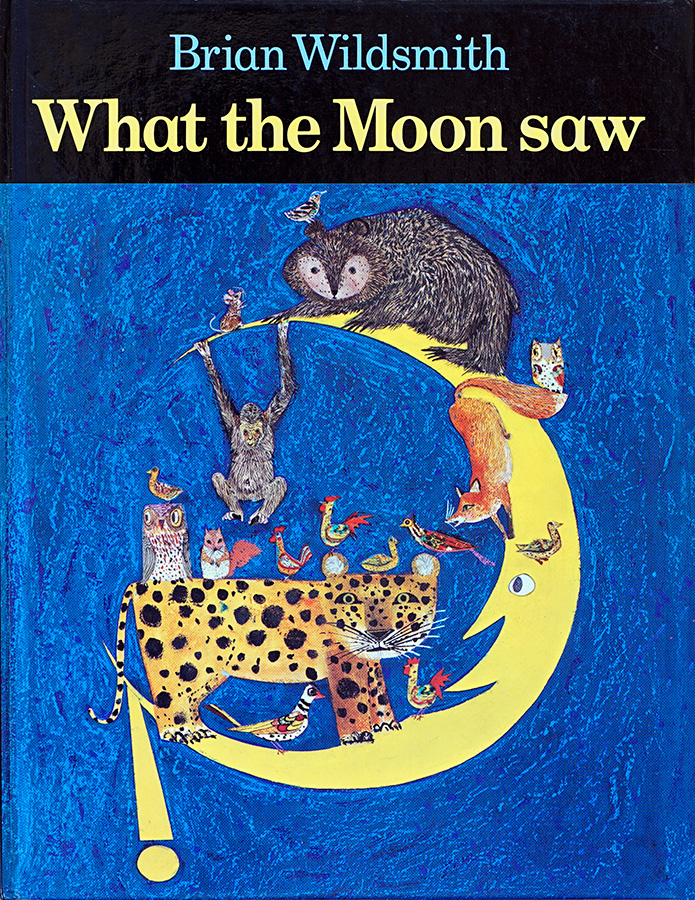

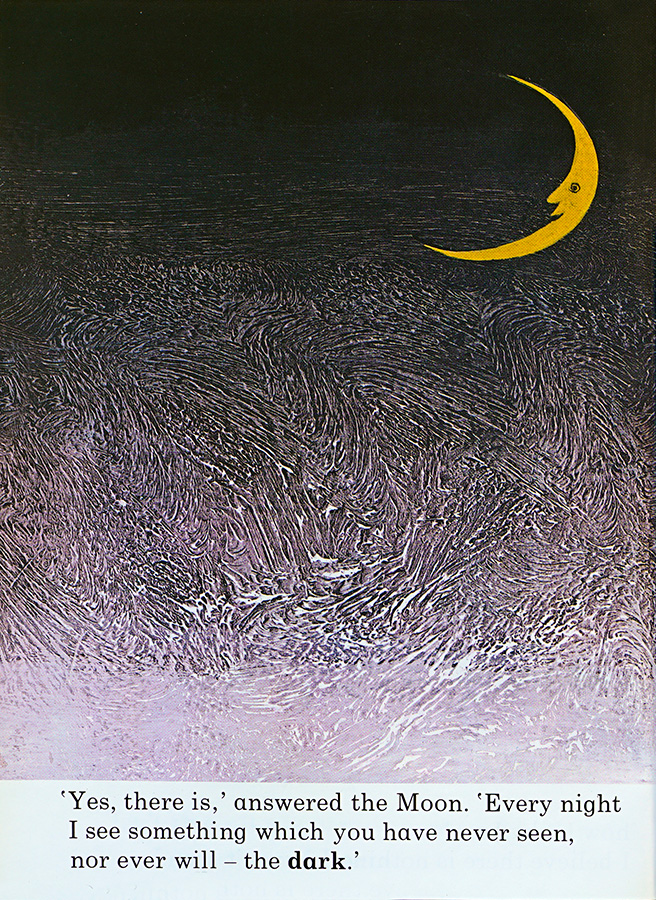

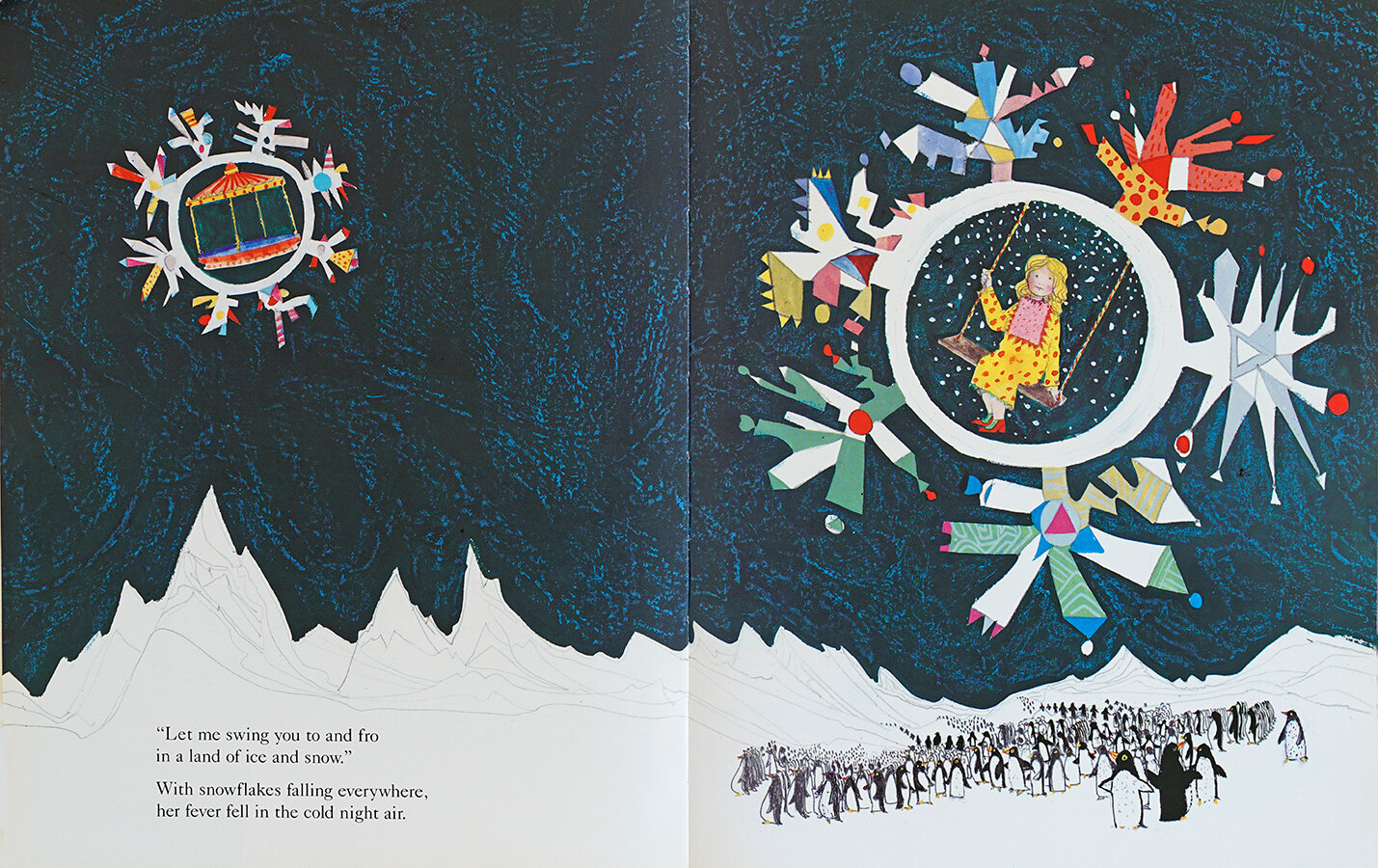

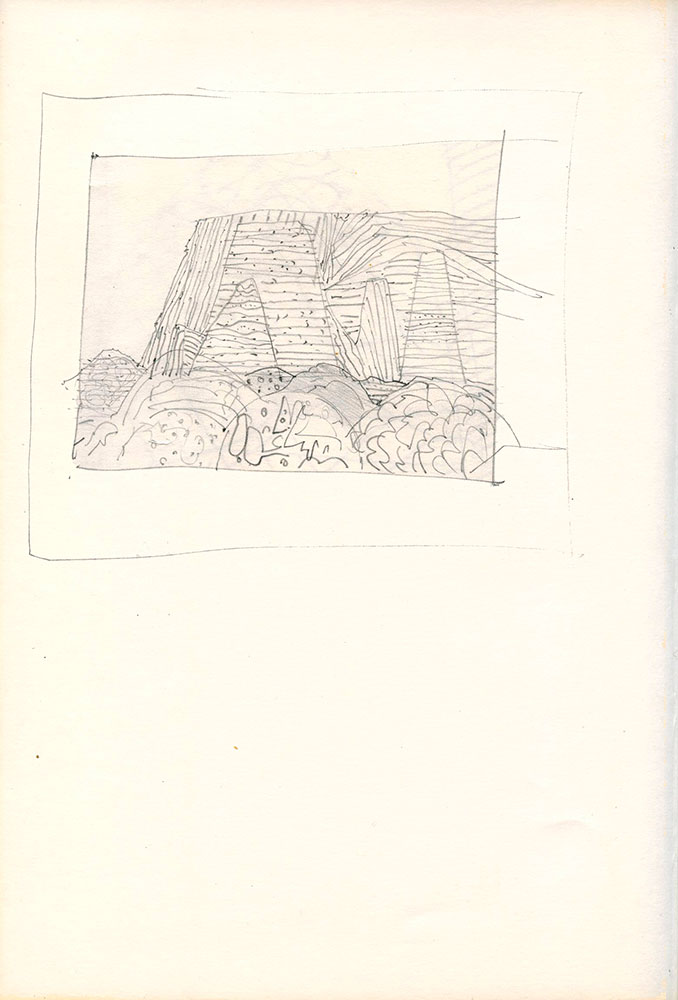

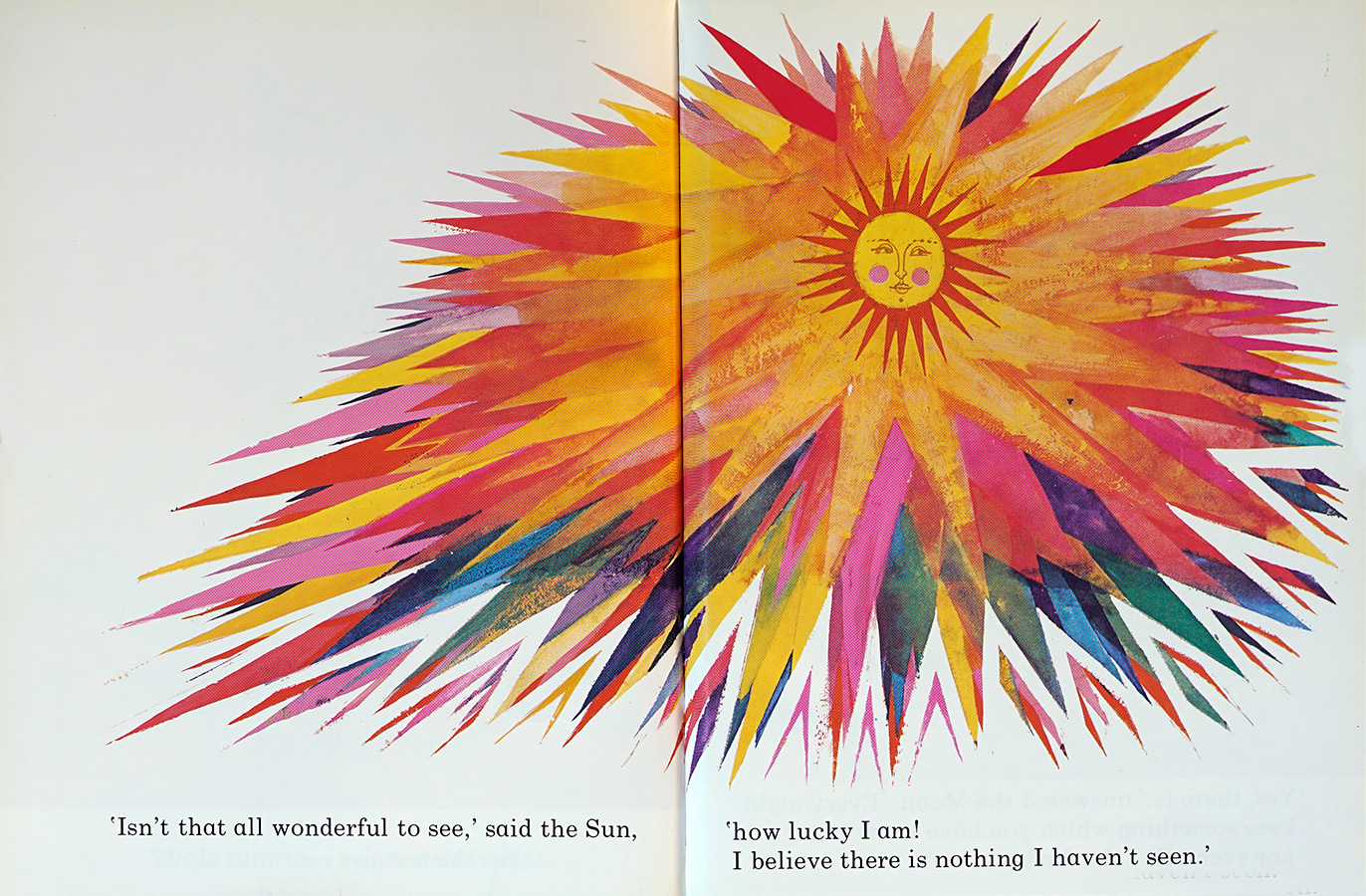

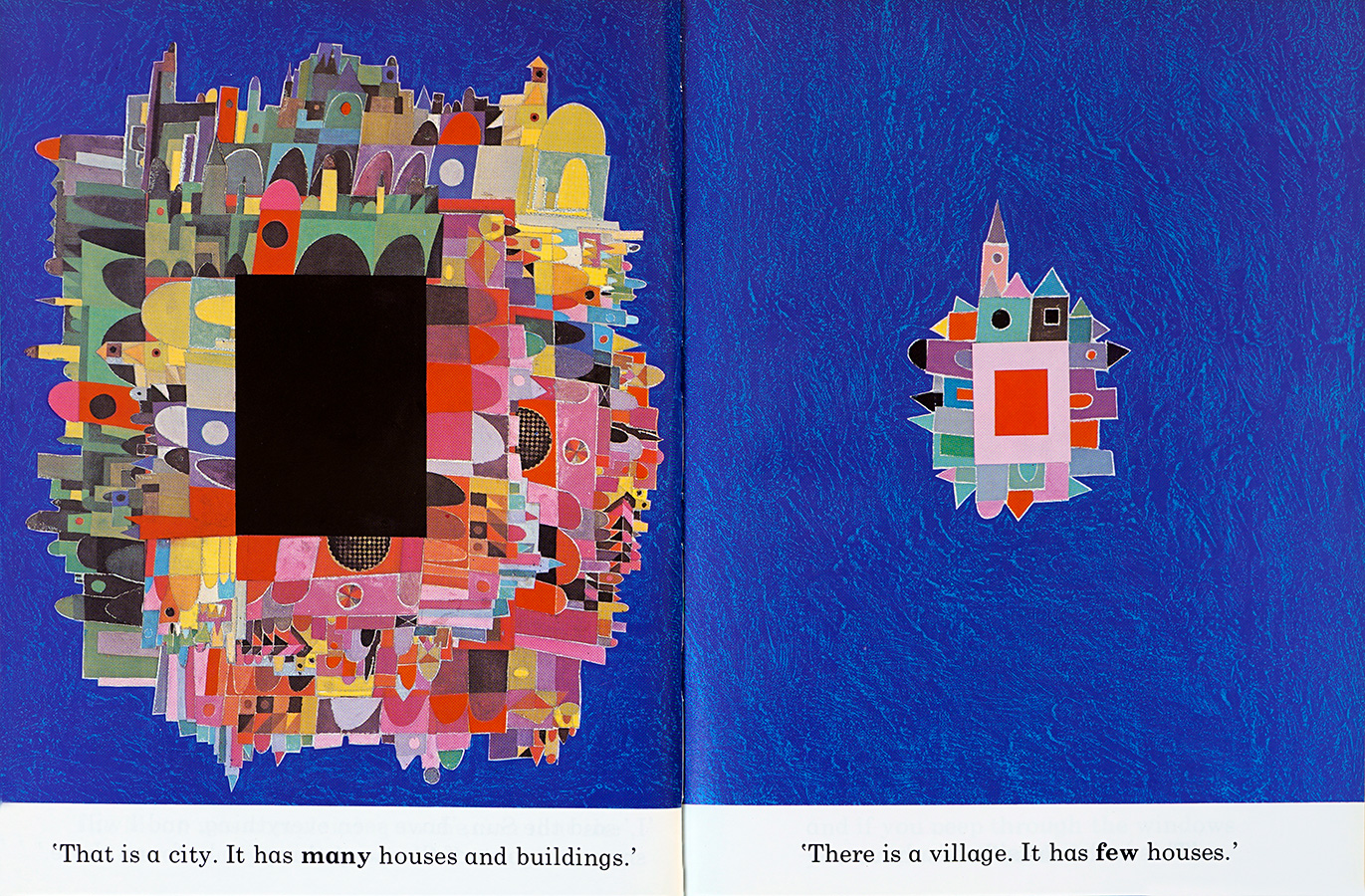

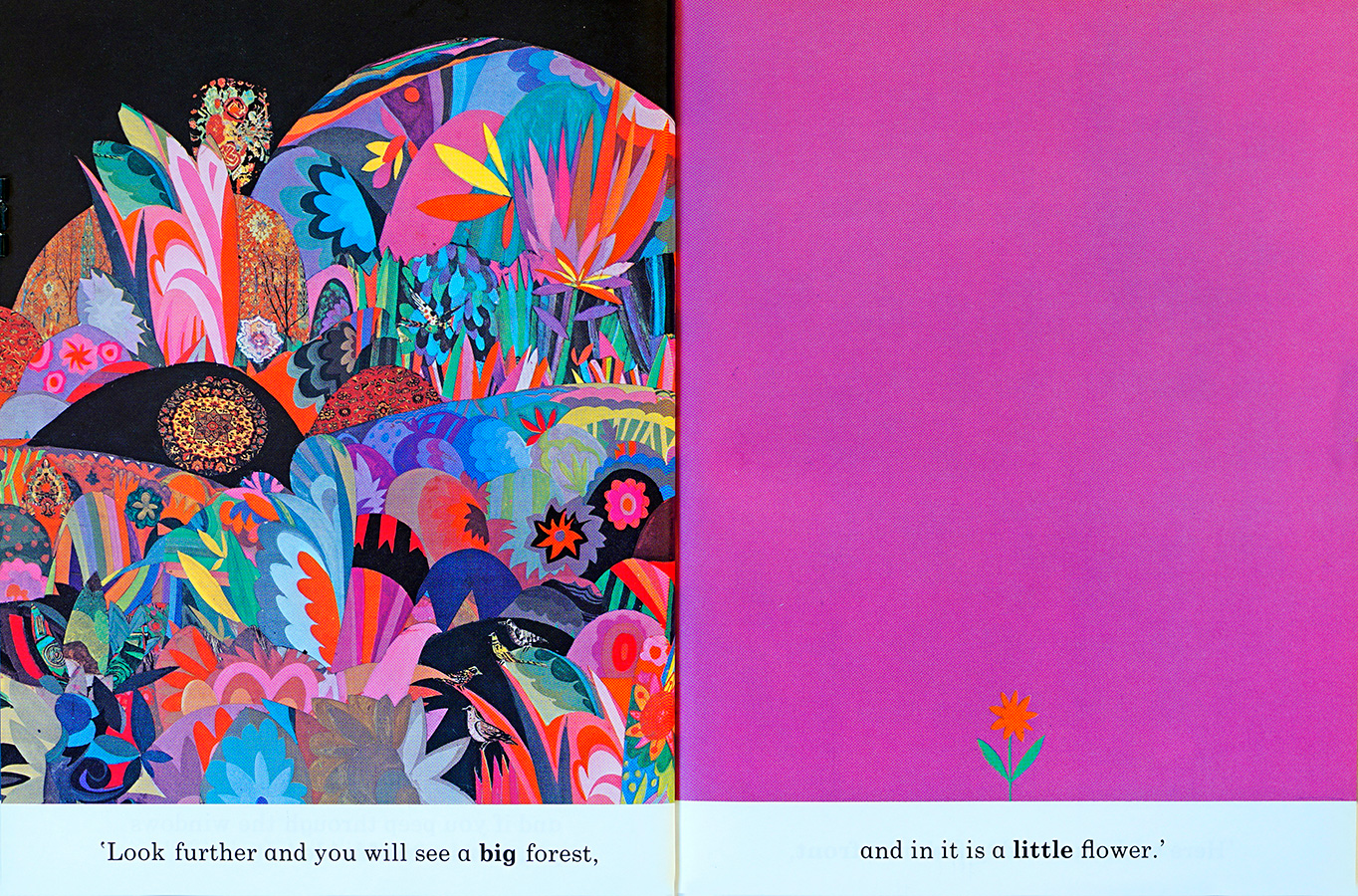

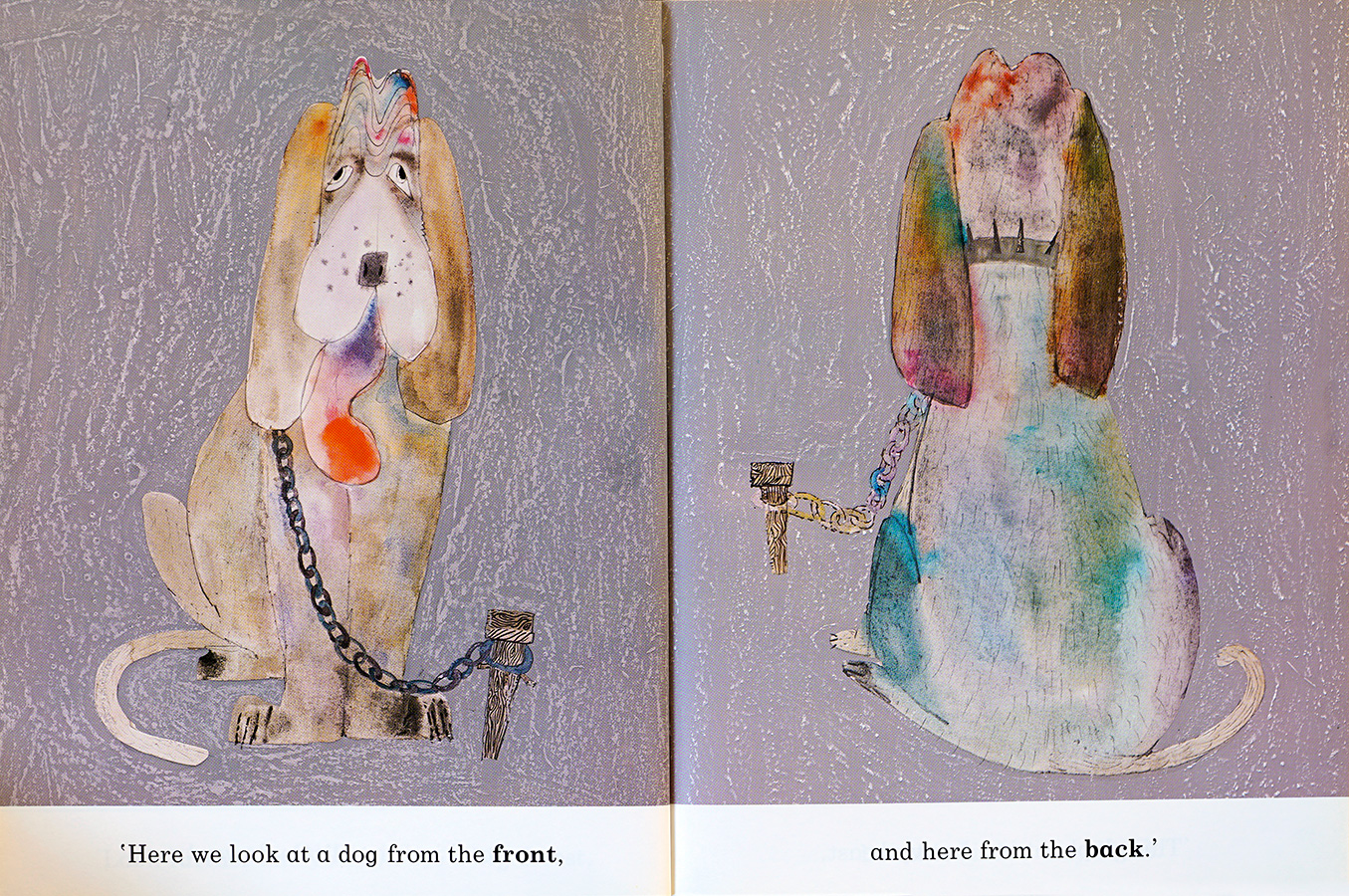

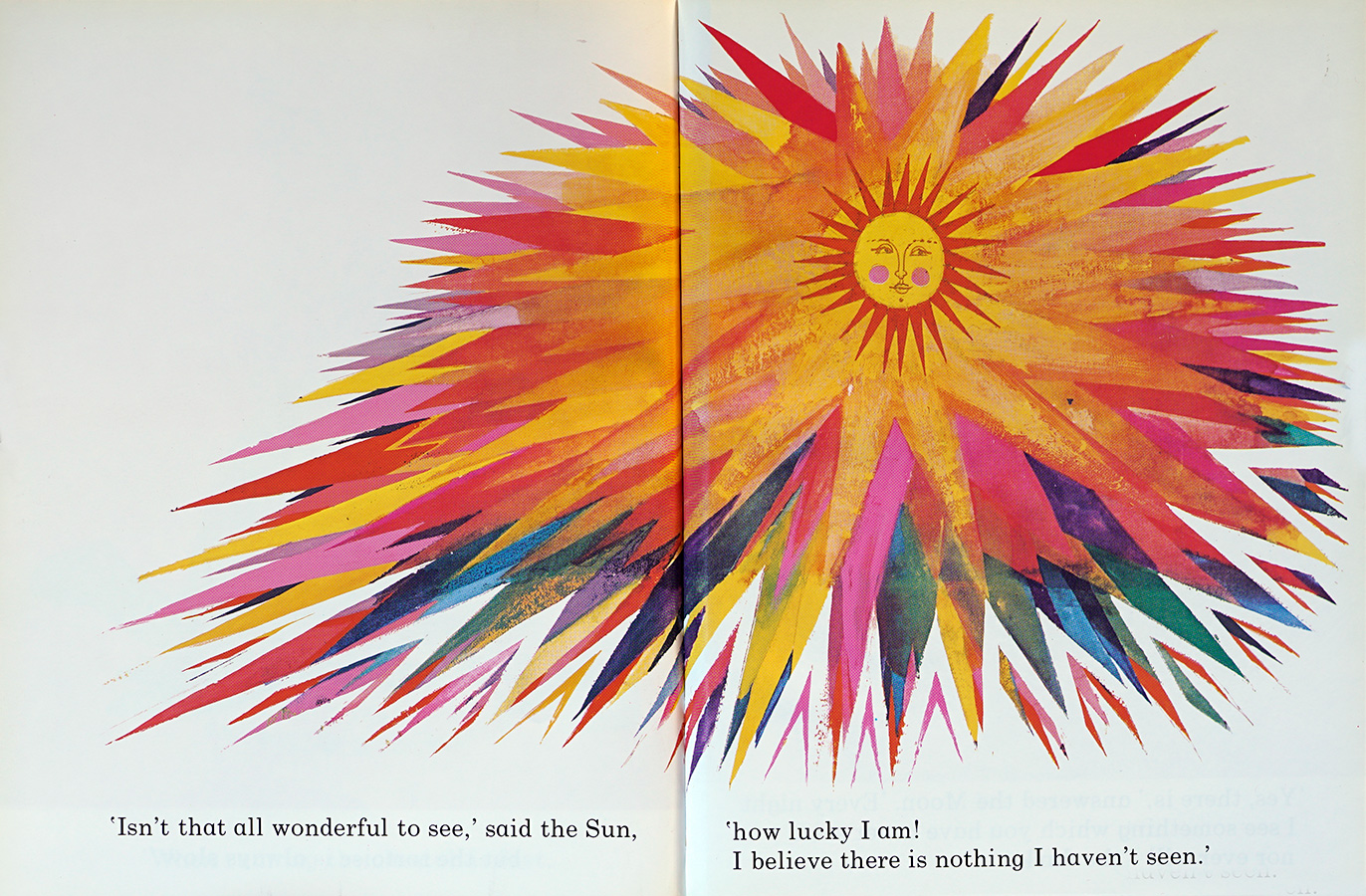

The following book, What the Moon saw, depicted as “an experience in art,” by The Wilson Library Bulletin, came out in 1978. It is a book of concepts built around a dialogue between the sun and the moon. Unfortunately, it resulted in a split between Oxford University Press and Franklin Watts who wanted various changes made with which Brian refused to comply, on the grounds that they would spoil the book’s structure. To his despair Franklin, a dear friend, died a few months later.

1978 was the 500th anniversary of Oxford University Press and to “celebrate this event,” said Brian, “I was invited by them to give a series of talks in Japan, Australia and New Zealand. I travelled with Aurélie, who had accompanied me on previous business trips. She was a wonderful companion and a very astute observer and social decipherer, especially of the different codes of behaviour of the Japanese. She was also immensely happy that we had time to travel for our own pleasure afterwards and reconnect with members of her family, who just after World War II, had been sold the dream of a new life in Australia, seduced by a boat fare of just £10.”

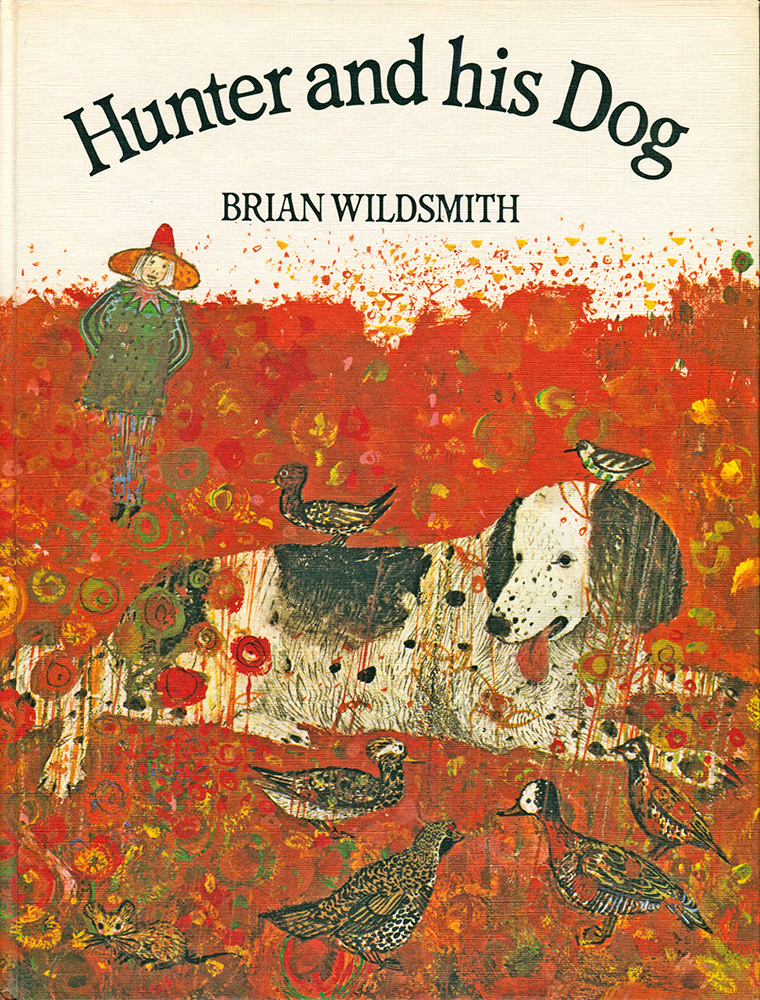

The subject of Hunter and his Dog, published in 1979, is, globally, one of compassion. Brian introduces this virtue to his young audience with the story of a clever hunting dog who, through his natural instinct for care, demonstrates the importance and value of the preservation of life to his master. The inspiration for this book came from Brian and family witnessing a quite unexpected and most touching series of events. Our dog was very sick and the next door neighbour’s dog, who usually stayed away, turned up daily to lick his head, snout and ears in what we believed was an attempt to make him better. “Our dog had brain tumours and eventually died,” said Brian, “but I had been overwhelmed by the compassion that Sherif, the big macho Airedale, had shown Vanic, the tiny Dachshund and I wanted to express it in a book.”

A book about the virtues of care and compassion inspired by events concerning the family’s dog, Vanic.

Book cover aside, all photos are of the original illustrations.

DOCUMENTATION & RESEARCH

Here again Brian shows that he was not only a great and imaginative painter, but also a superb draughtsman who knew so convincingly and with such poetry, how to represent the animals, their habits and habitats, as well as the host of other subjects he chose to include in his compositions. Whether for Hunter and his Dog, past books or ones to come, the trueness and the artistry of his drawings is outstanding. To achieve this it takes talent of course, and thousands of hours of work, but it also requires documentation and research. When Brian lived in London, Clapham Library was just around the corner. His membership card permitted him to have six books on loan at a time but the staff allowed him to borrow armfuls of them. Many never got taken back to the library. We found them 60 years later in his bookcase after he died. He wasn’t a pilferer but he could be incredibly absent minded! When he travelled, he also always had a camera with him to photograph the animals, houses, farms, churches and landscapes which, with his library books, would be scattered around his desk for reference. The model for the dog in Hunter and his Dog was that of the family’s French cleaning lady Rosie’s husband, who was a fervent hunter himself. Brian wasn’t particularly fond of Gérard, but he did like his Irish Setter!

FROM MUSEUM TO CHURCH, GALLERY TO CATHEDRAL,

CATHEDRAL TO OUTER-SPACE

The flat in Rosas, Spain was sold in 1975. It was no longer required since the need for sunshine had been quenched by the family’s move to the south of France. From then onwards, Brian and Aurélie spent almost all of our school holiday time driving us throughout southern Europe from museum to church and gallery to cathedral. In addition to art being our father’s passion and travel our mother’s, Brian wanted his children to be immersed in, and comfortable with all that he had not had the chance to see or experience as a child, most particularly, the formidable knowledge and educational power contained in great art and architecture. It was his firm conviction that acquiring visual literacy was as vital and fundamental for a child’s education as maths and he often deplored how poor it could be in the makeup of many of the very people, whose jobs consisted of making visual decisions that affect the whole of society.

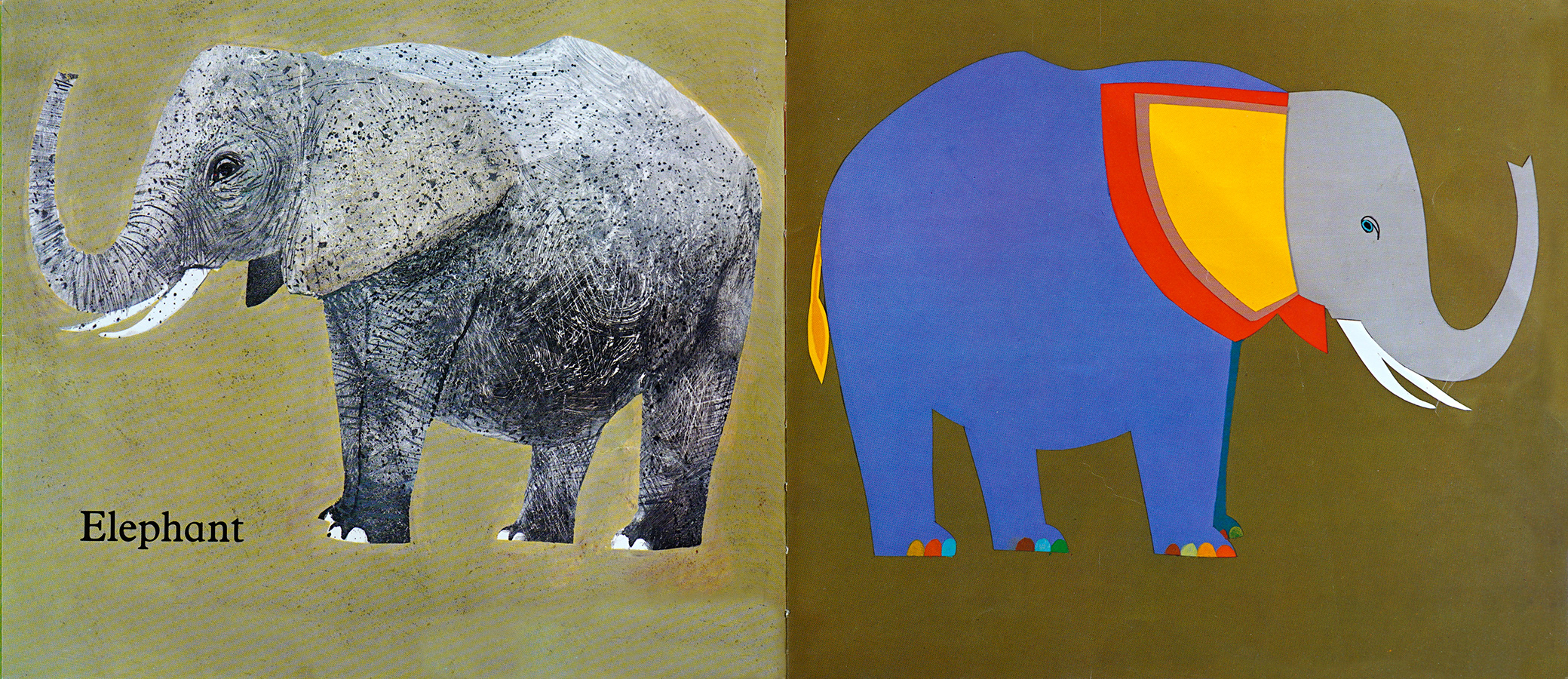

…the elephant even gets to don a spacesuit for his own kind of moonwalk…

ECOLOGICAL PRECURSOR

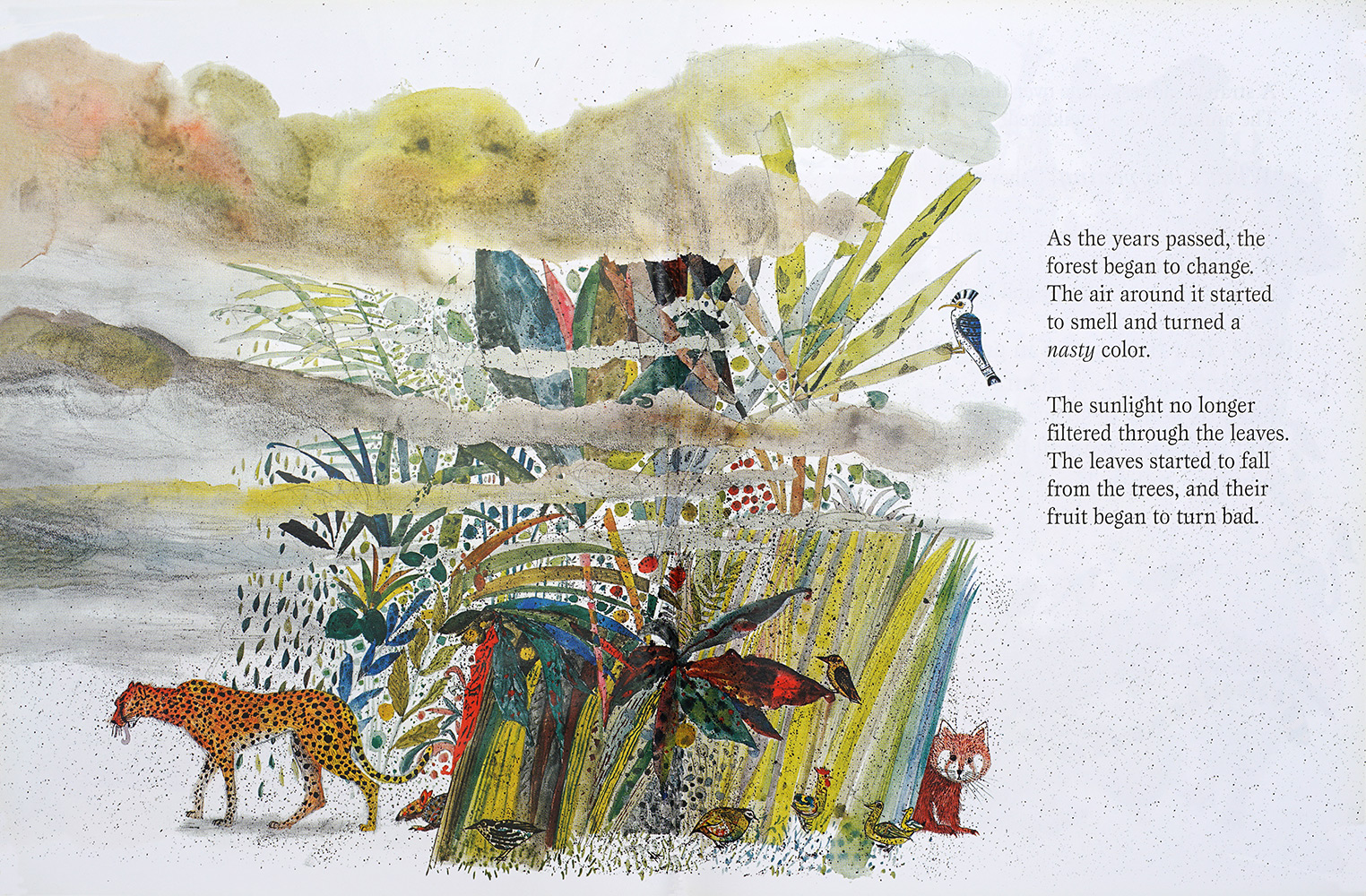

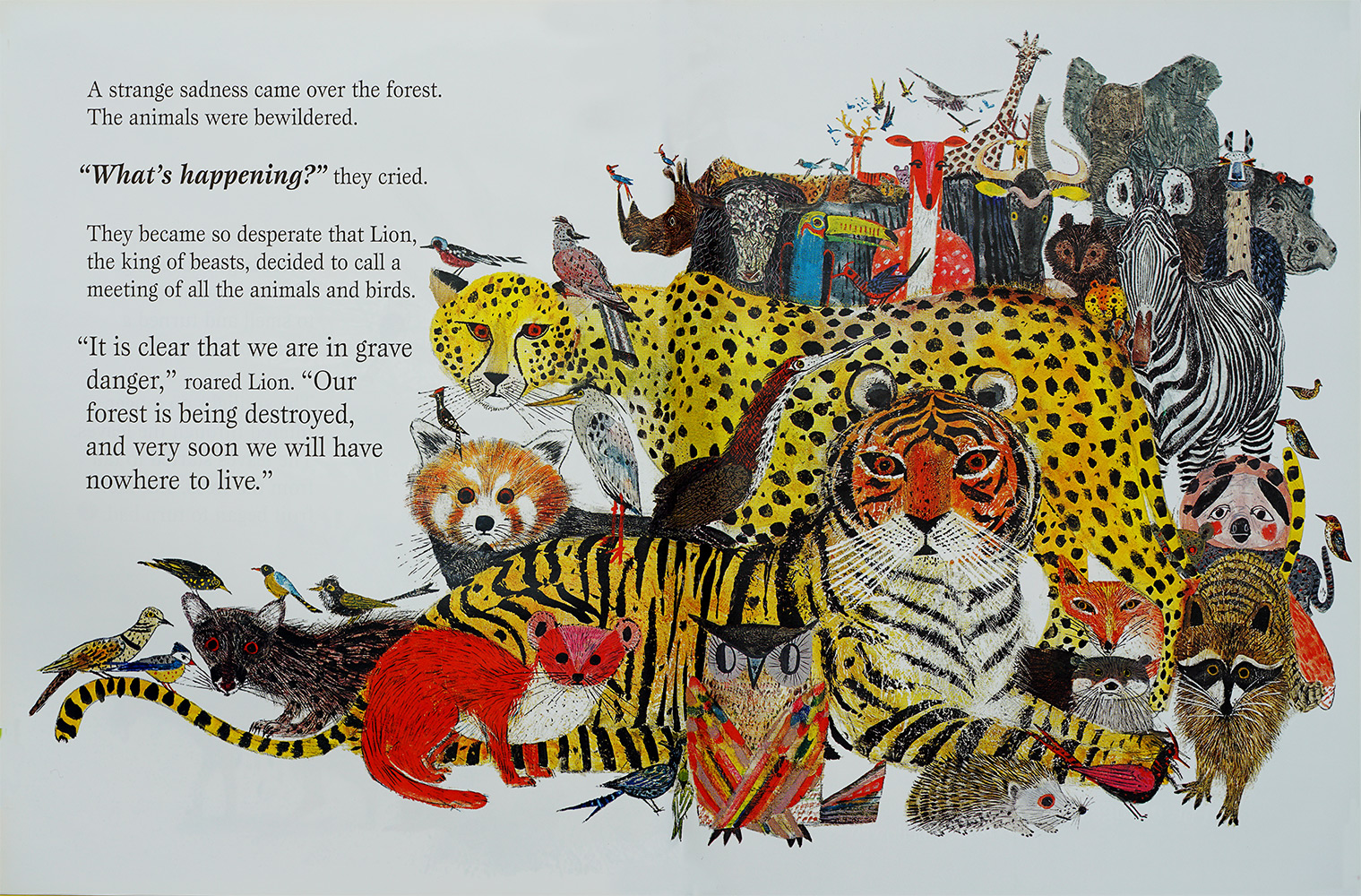

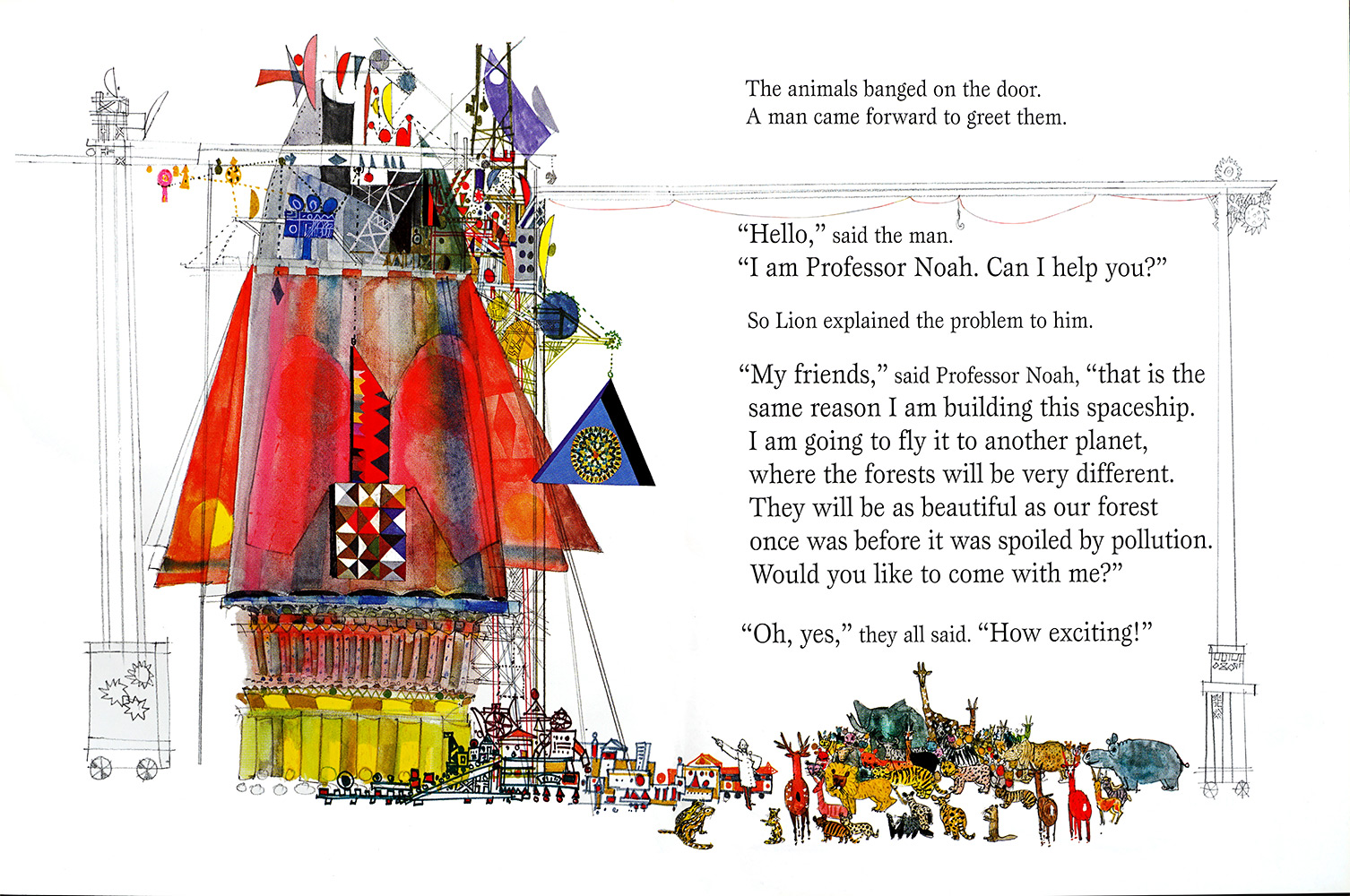

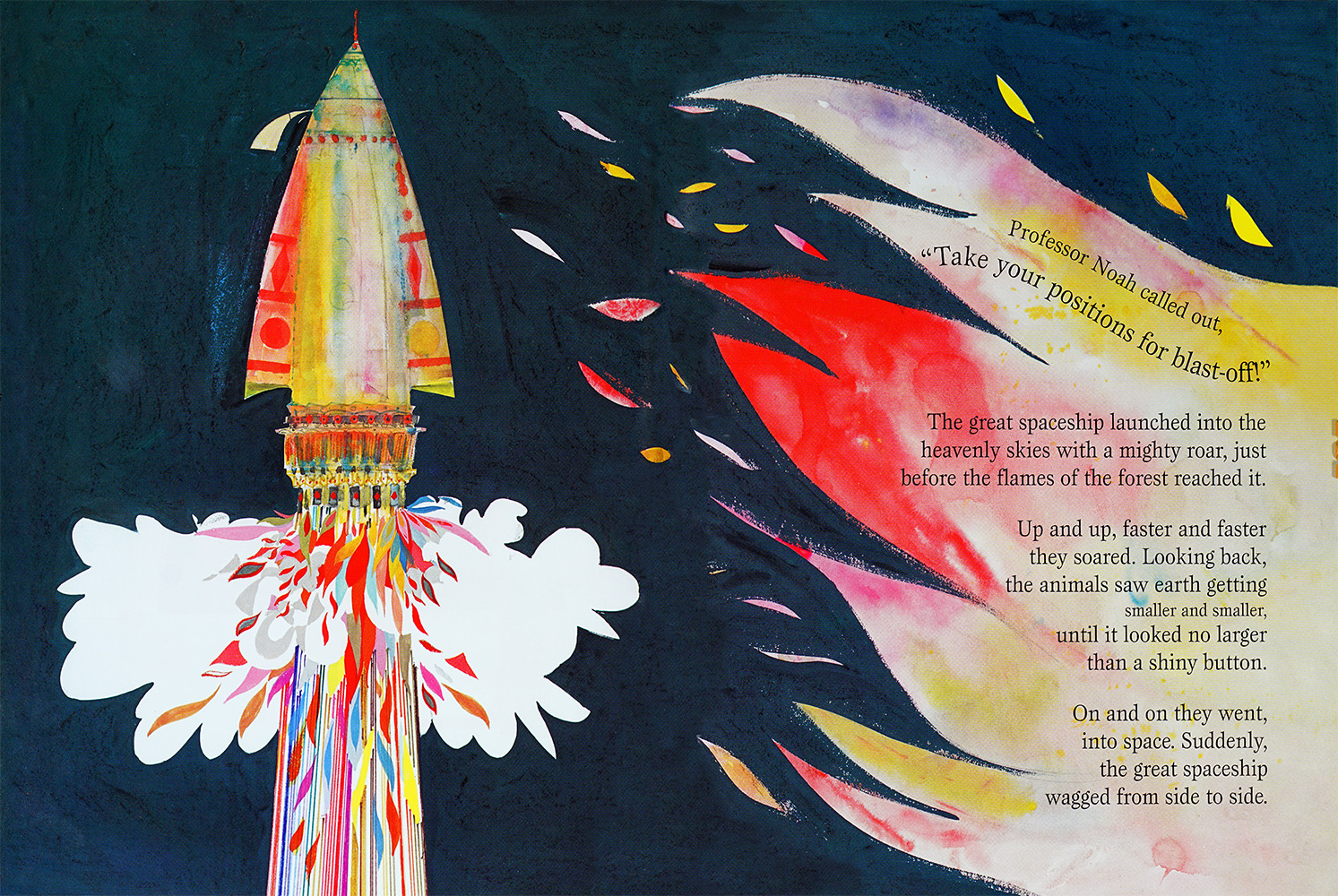

Another subject close to his heart, and that he regarded as fundamental, was ecology. In 1980 before it was fashionable or urgent to inform children of the importance of preserving our planet, Brian created Professor Noah’s Spaceship. It is a contemporised version of Noah’s Ark where the animals assemble around a great spacecraft in response, not to impending floods, but to their habitat’s pollution and the foreseeable climactic change. It is both witty and clever. Tragically, 40 years later, its once avant-garde message is now all too familiar to us all and Brian can be seen as a precursor of alert in this alarming domain.

Burgin Streetman, in vintage childrens books my kid loves.com has devoted many a post to Brian’s work and even wishes he had made wallpaper so she could wrap her whole house in his “colors and imagination”. When describing Professor Noah’s Spaceship she writes most flamboyantly, "You gotta hand it to this guy, he does love animals… in this one, he actually creates a world where he can save the animal kingdom from certain extinction via a rocket ship into outer space. Cool, no? It is the tale of Noah's Ark reimagined in a world where the earth's resources have been squandered and destroyed, and in an attempt to save themselves, the animals find Professor Noah and his magical, mystery time machine. Groovy baby! Instead of traveling through space, they travel through time… the elephant even gets to don a spacesuit for his own kind of moonwalk and they end up back on earth before we ruined it with our smog and our cars and our disposable sandwich bags… Great green message for the space age, plus drop-dead awesome illustrations from one of Britain's masters.”

In July 1980 the journalist Martin Gervais, writing for the Canadian newspaper the Windsor Star, rightly pointed out, “The term ‘pollution’ has finally crept into juvenilia and it comes by way of Brian Wildsmith’s rich gouaches and fable. The fable, drawing upon the Old Testament story, should create a storm because it effectively informs children about the destructive nature of pollution. It's virtually saying the world is intolerable and it will necessitate nothing short of a modern day Noah’s Ark to flee it.”

In 1980, long before it became a subject of such dramatic urgency, Brian wrote and illustrated Professor Noah’s Spaceship, a tale about pollution and climatic change and its consequences on a group of animals living in the forest: “Our children are the building blocks of our civilisation, if we care about them we must care about the society they live in, maintain an ecological balance and treat our wonderful world with respect and love.”

On the title page, (seen below) there is an amazing drawing of Professor Noah’s design for the spaceship, surrounded by mathematical formulae, symbols and engineering plots. It is a reminder of his everlasting fascination for science, numbers and mathematics, as well as his passionate admiration of Leonardo da Vinci. Brian strongly believed that the responsible use of science could liberate mankind from servitude. While some detected a utopian leaning in some of his opinions on the subject, or certain aspects of his outlook on life in general, what better place to be for an author dedicated to helping children grow up in the context of their inherent innocence.

The title page from Professor Noah’s Spaceship. A reminder of Brian’s love and fascination for the sciences and engineering. He didn’t frame many of his illustrations, but this one hung in our home.

While writing this biography, Brian’s two granddaughters, Carla and Ornella, who are now showing their own kids their grandfather’s work, reminded us of an event they had proudly experienced when they were little girls. They had accompanied him to the International School in Nice, where he had been invited to give a talk about the book because of its environmental message. After this and the accustomed questions and answers session, the 6 - 10 year olds suddenly stood up and sang a special song they had written and put to music with the help of their teacher. It was, surprise, surprise, called Professor Noah’s Spaceship!

I LIKE TO USE ANIMALS FOR THEIR ALLEGORICAL FUNCTION

WHEN REPRESENTING HUMAN NATURE

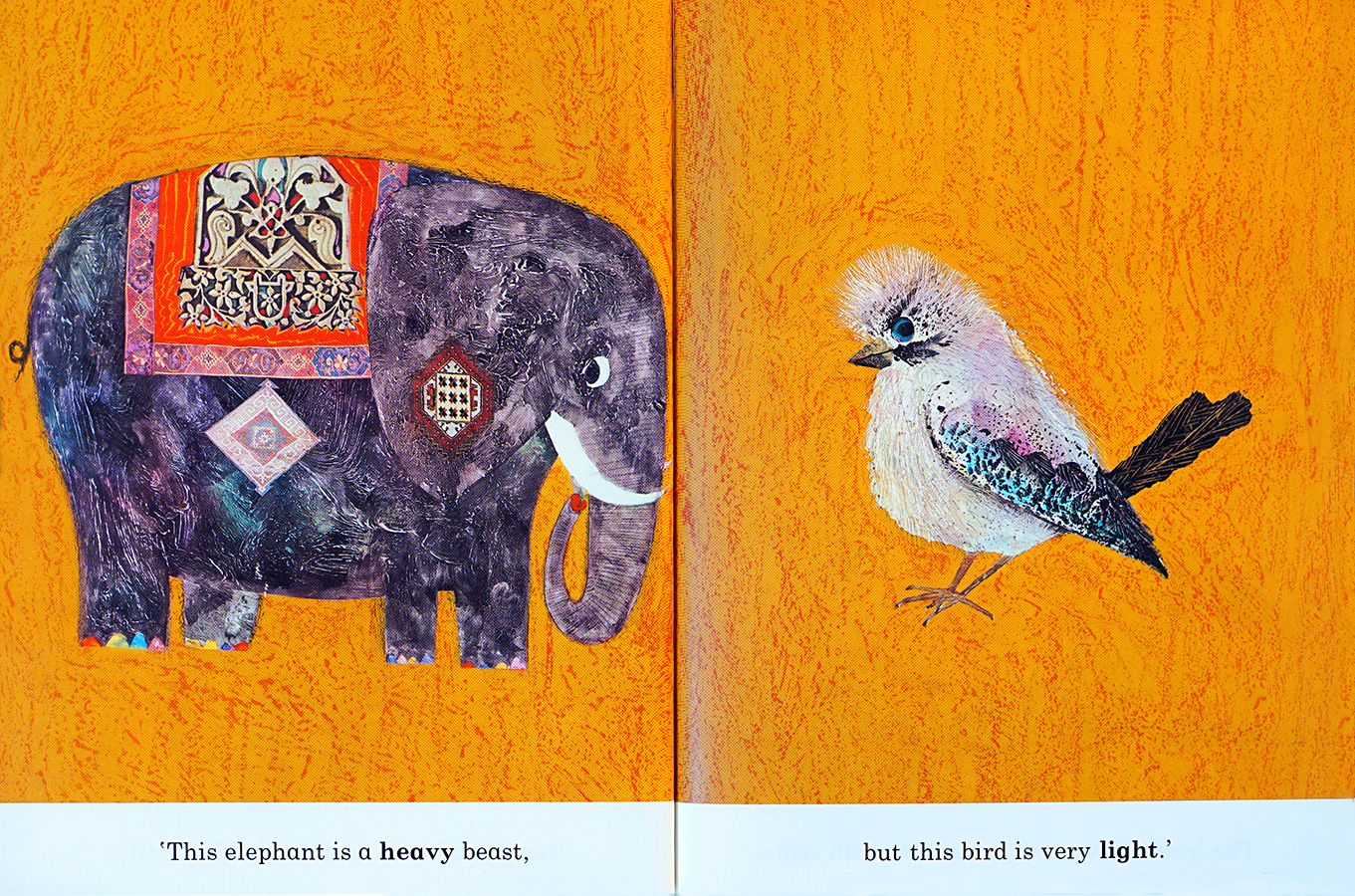

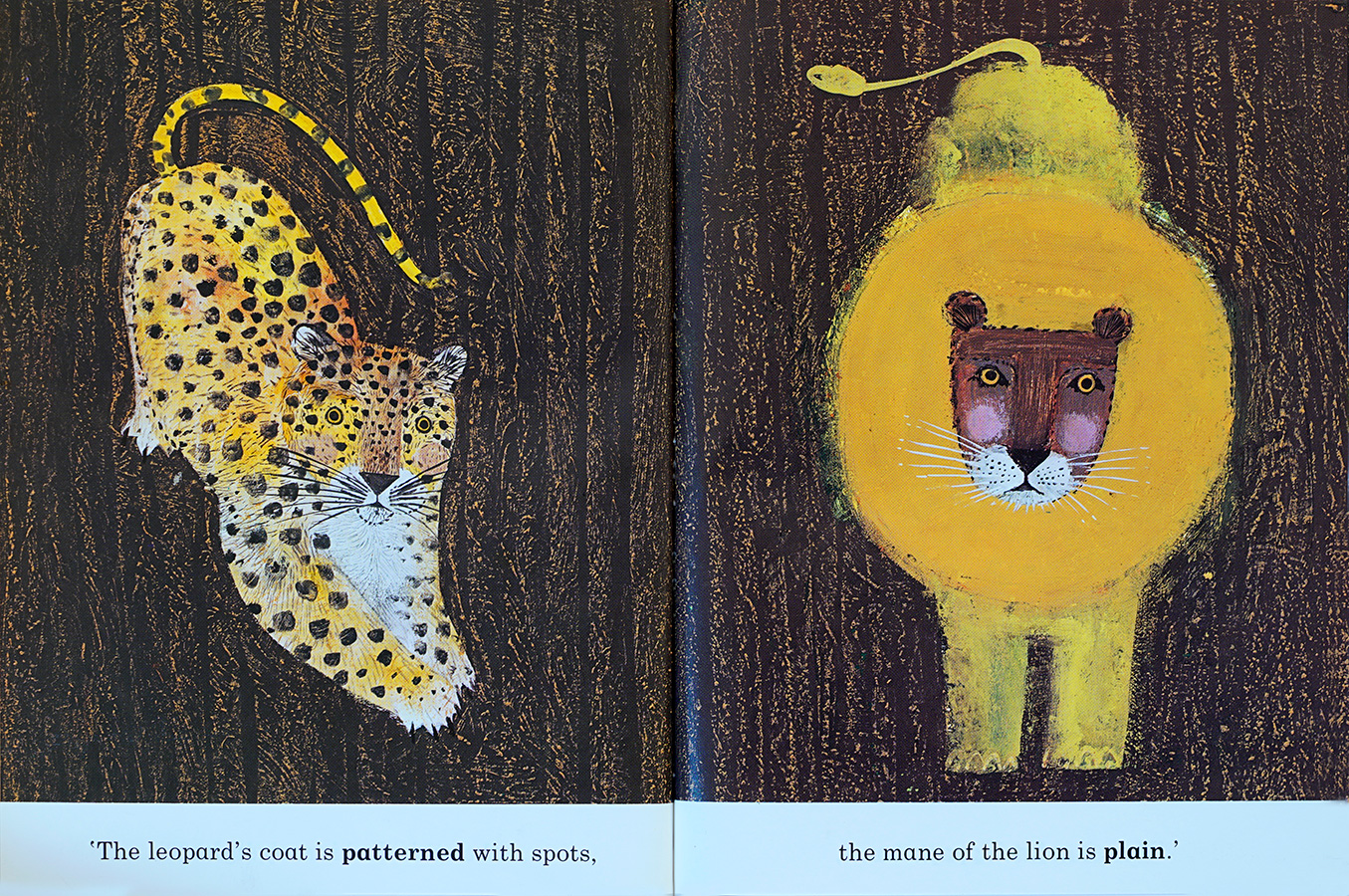

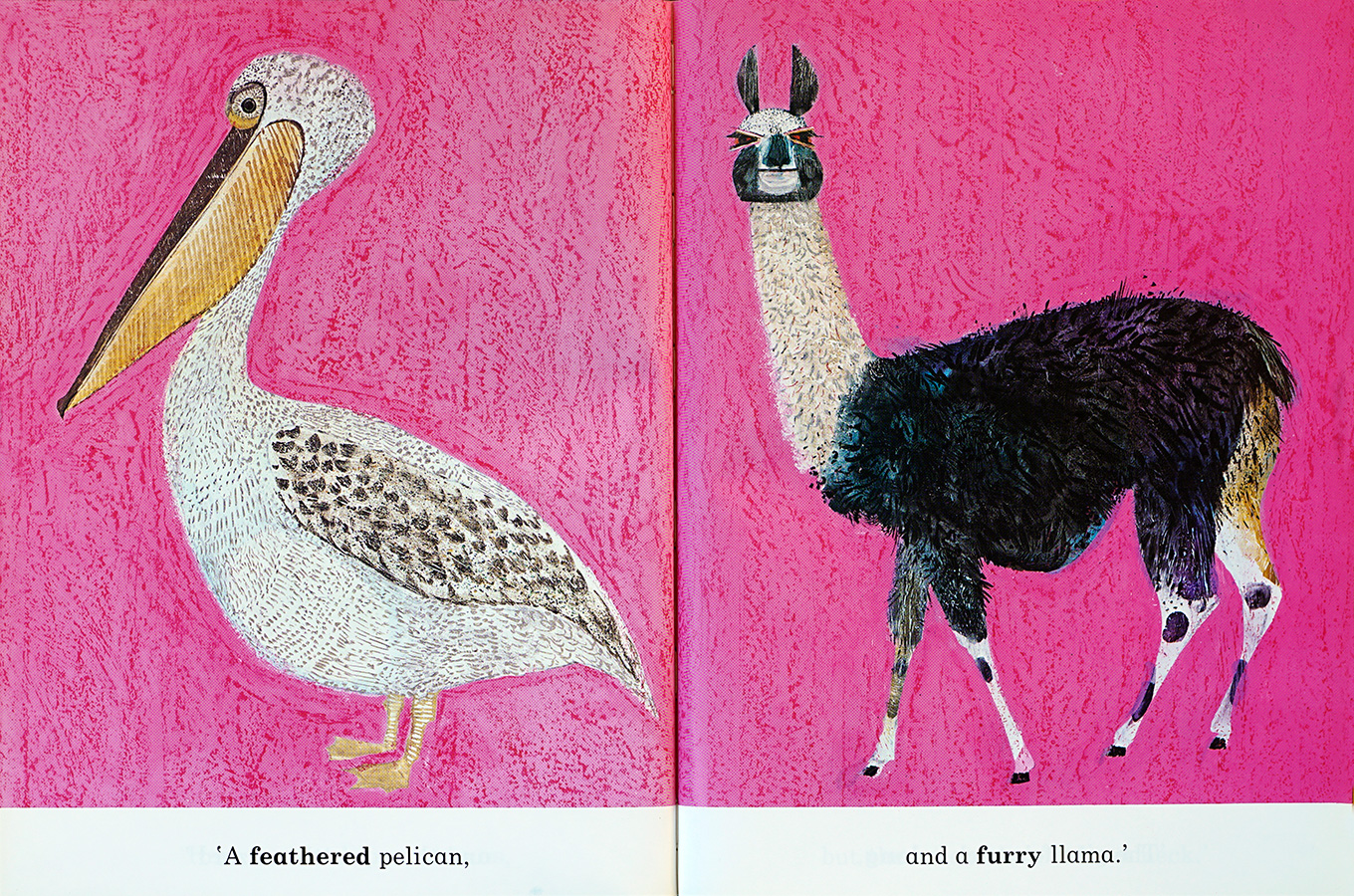

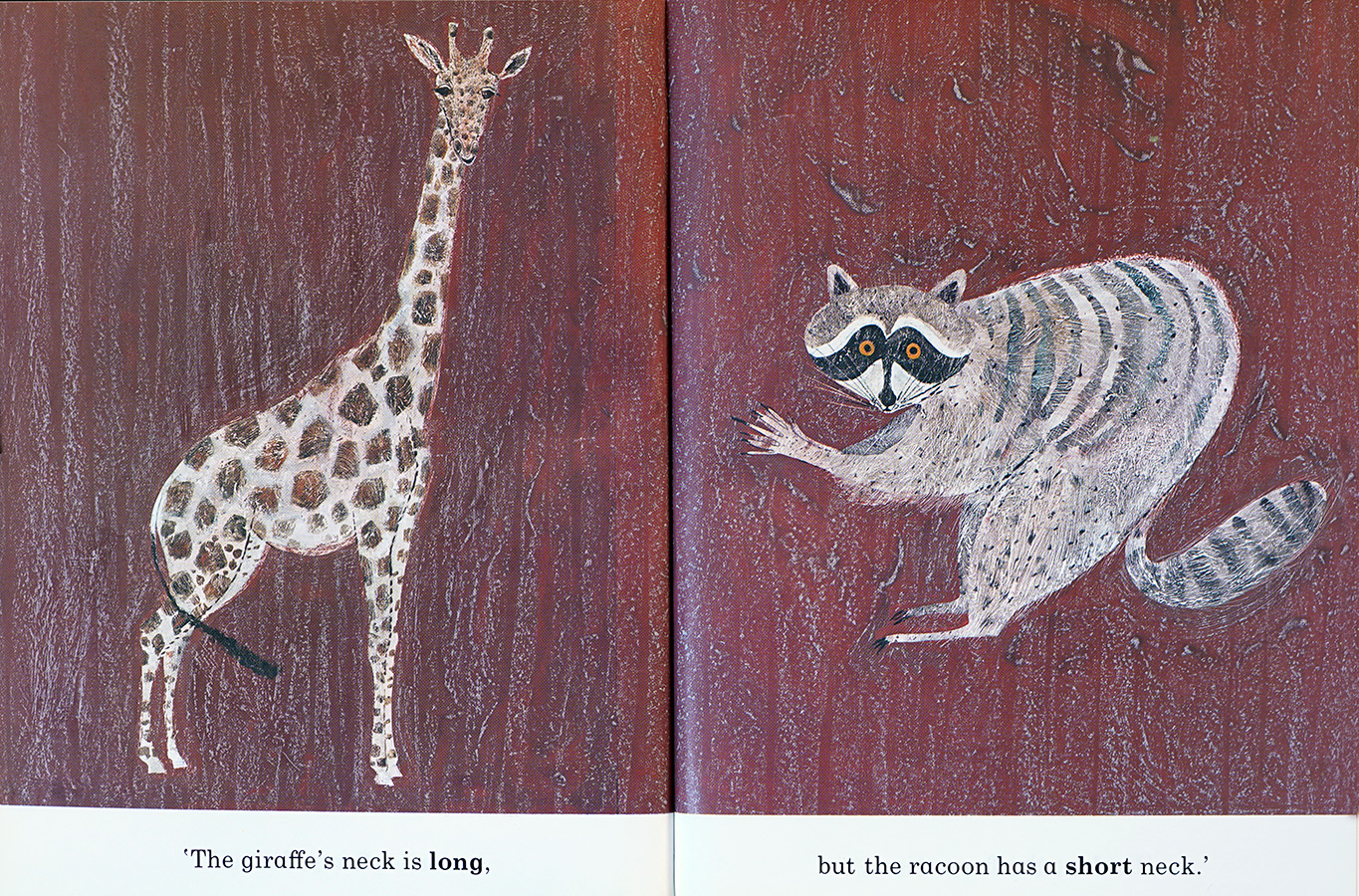

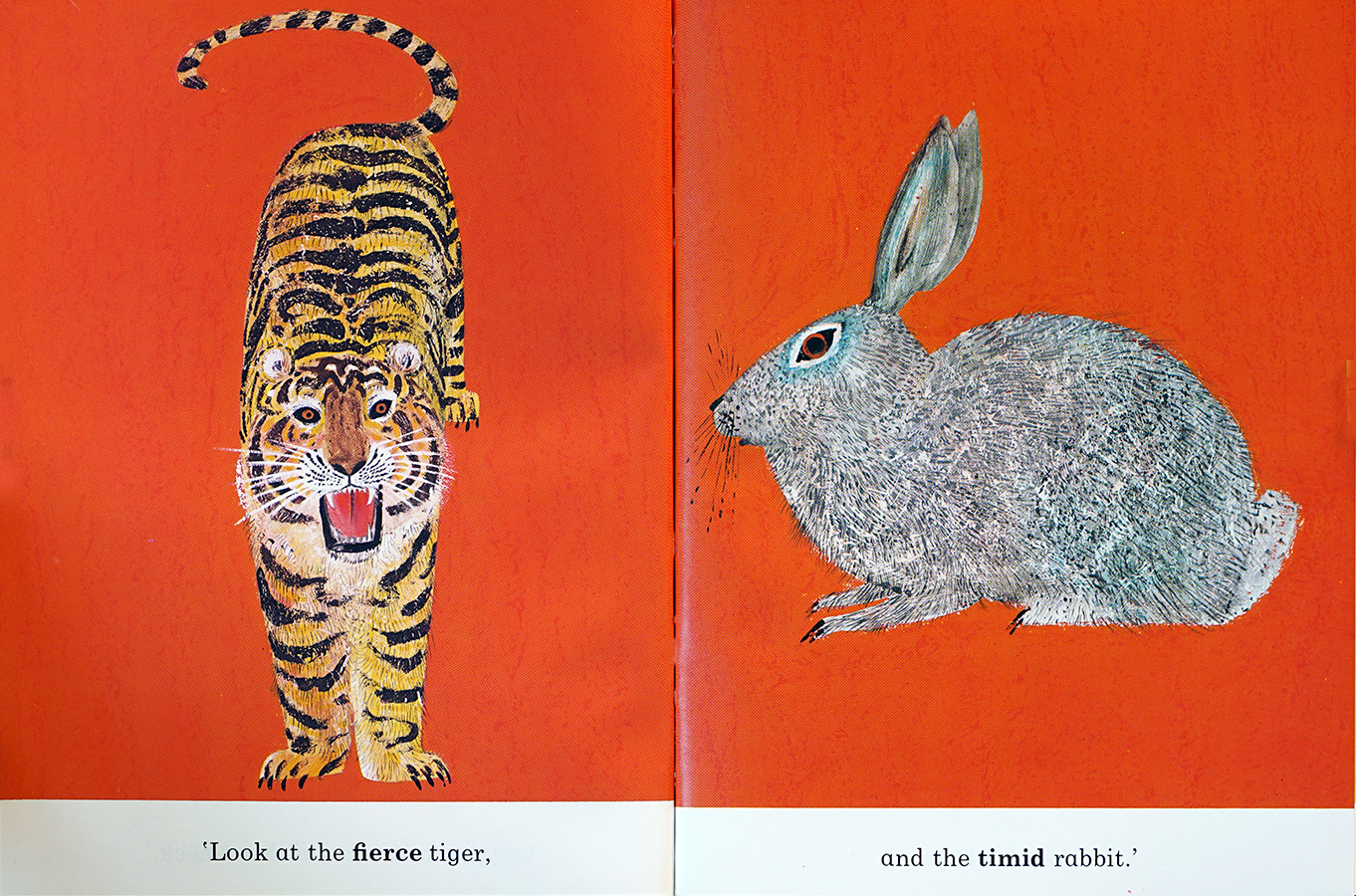

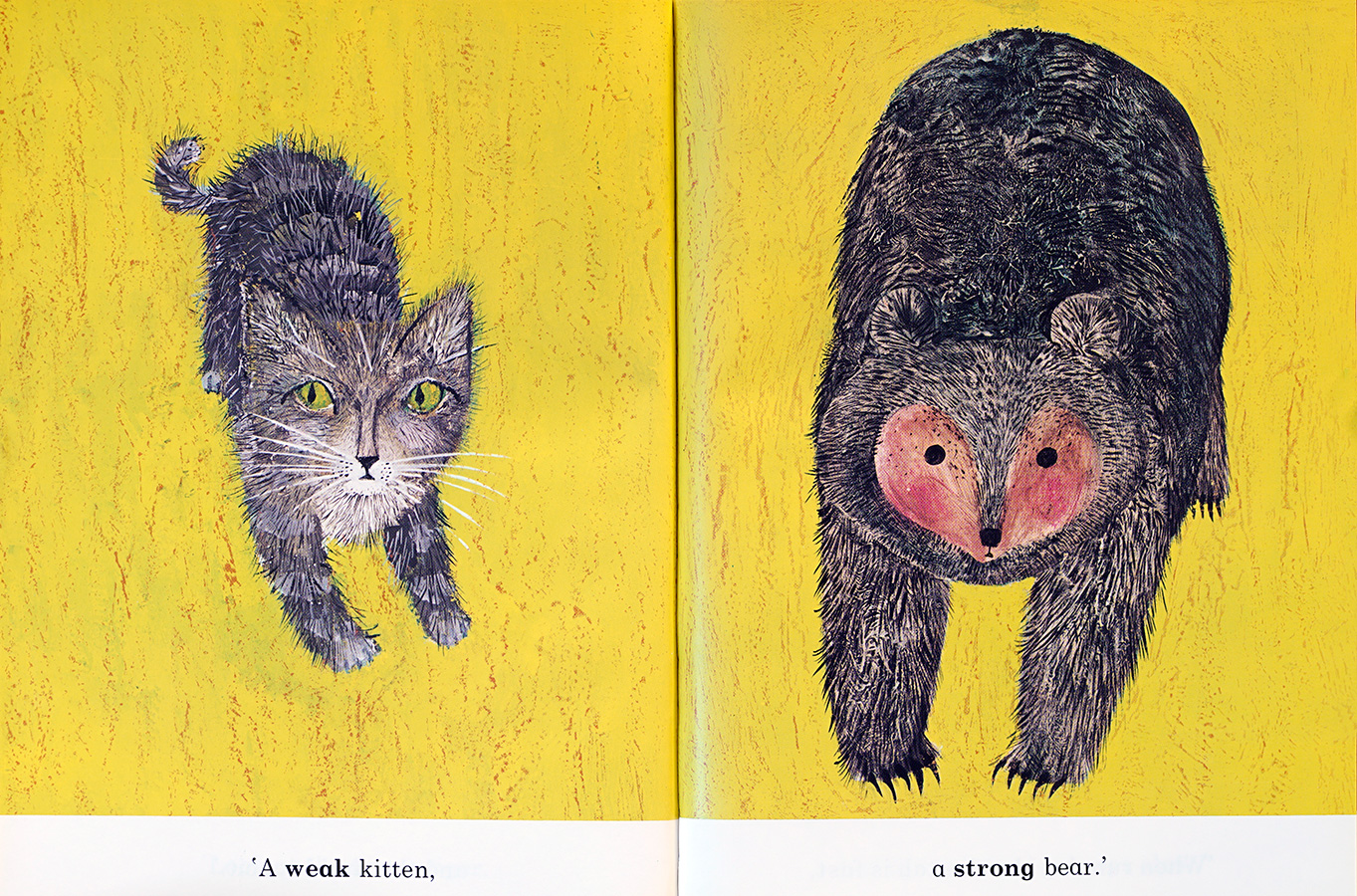

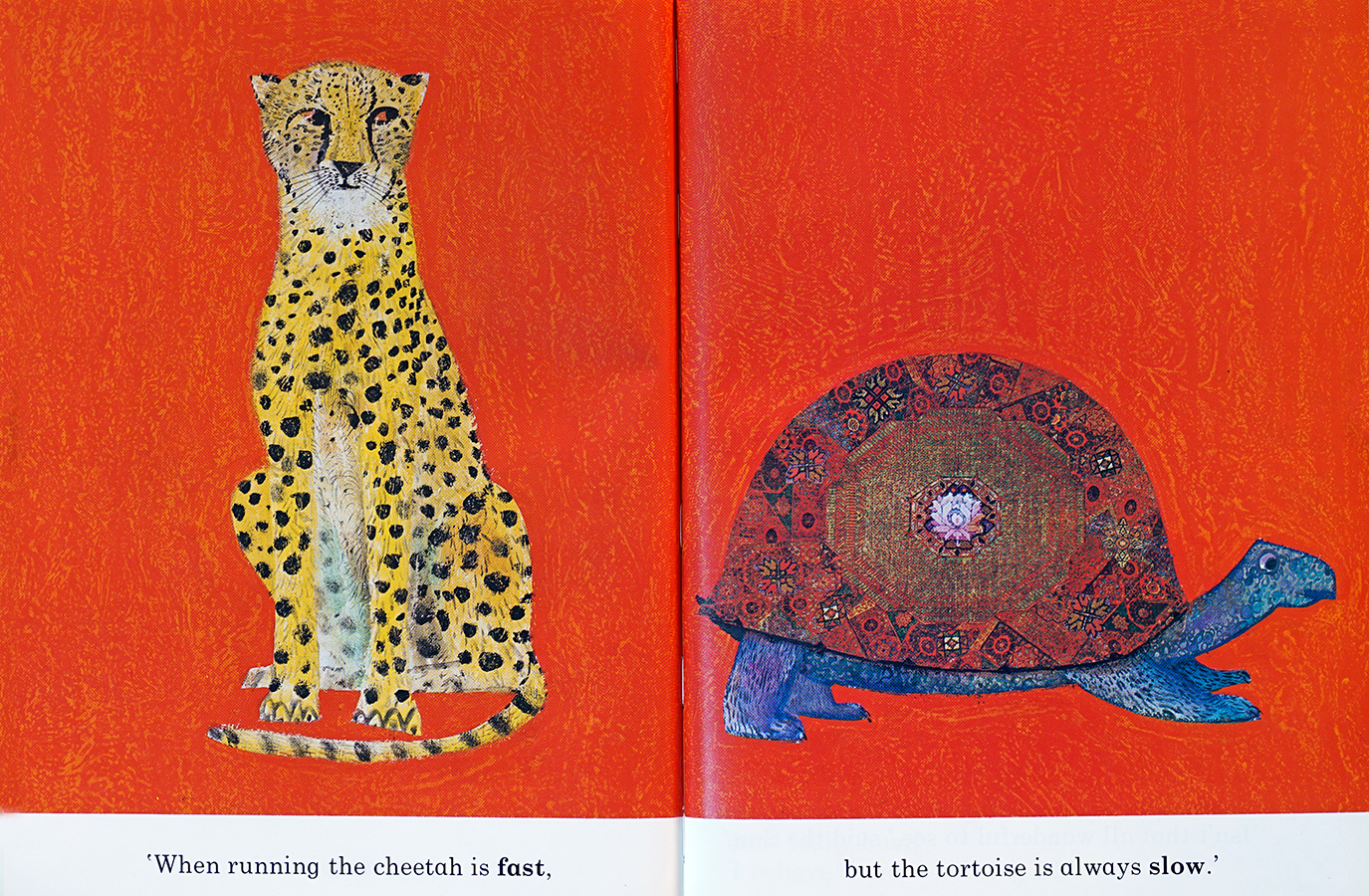

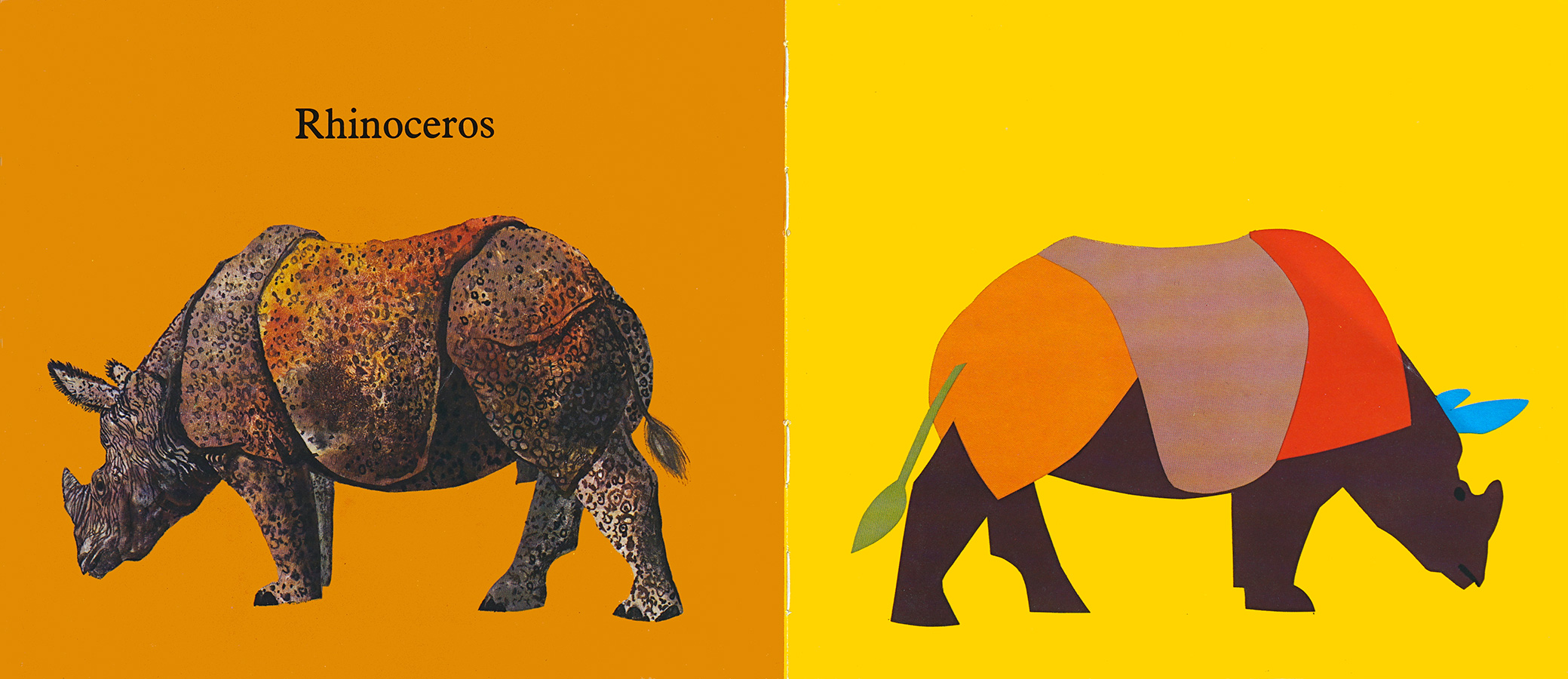

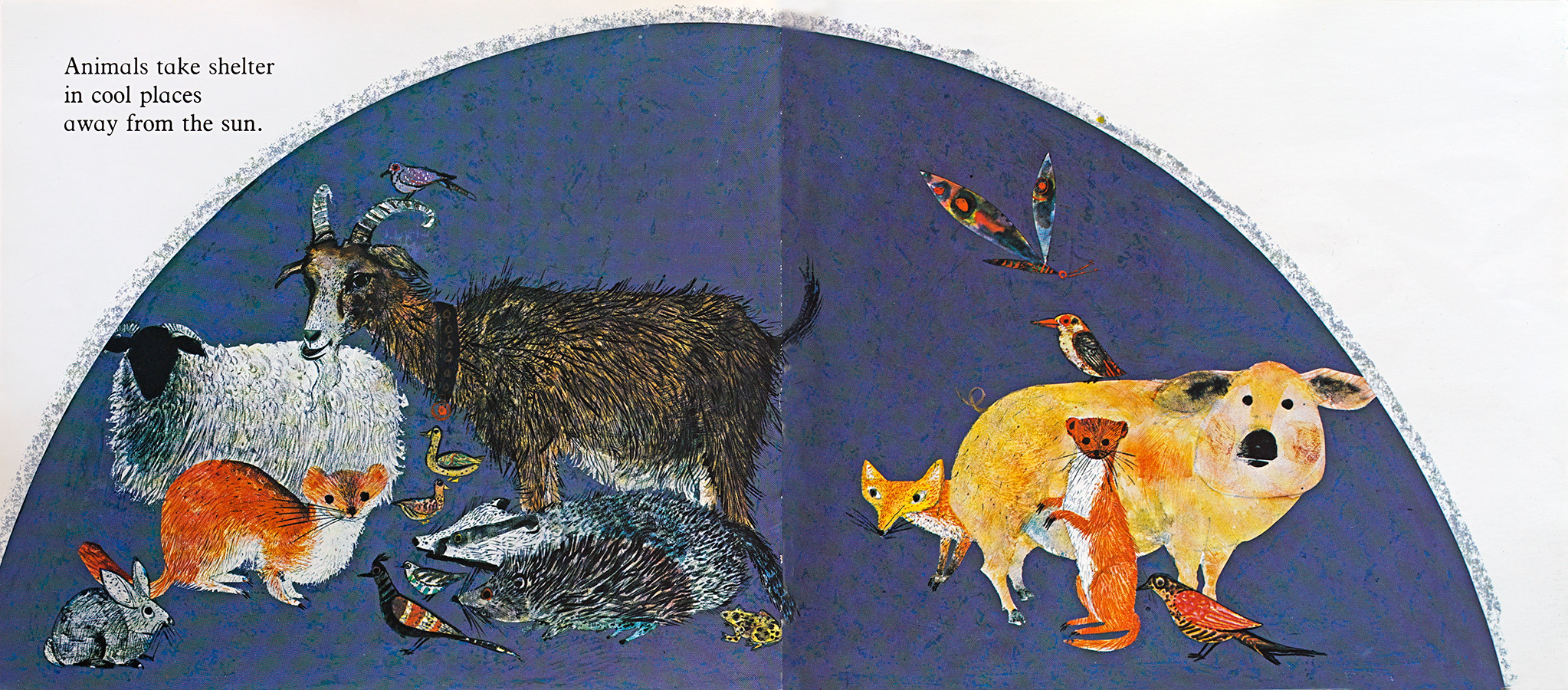

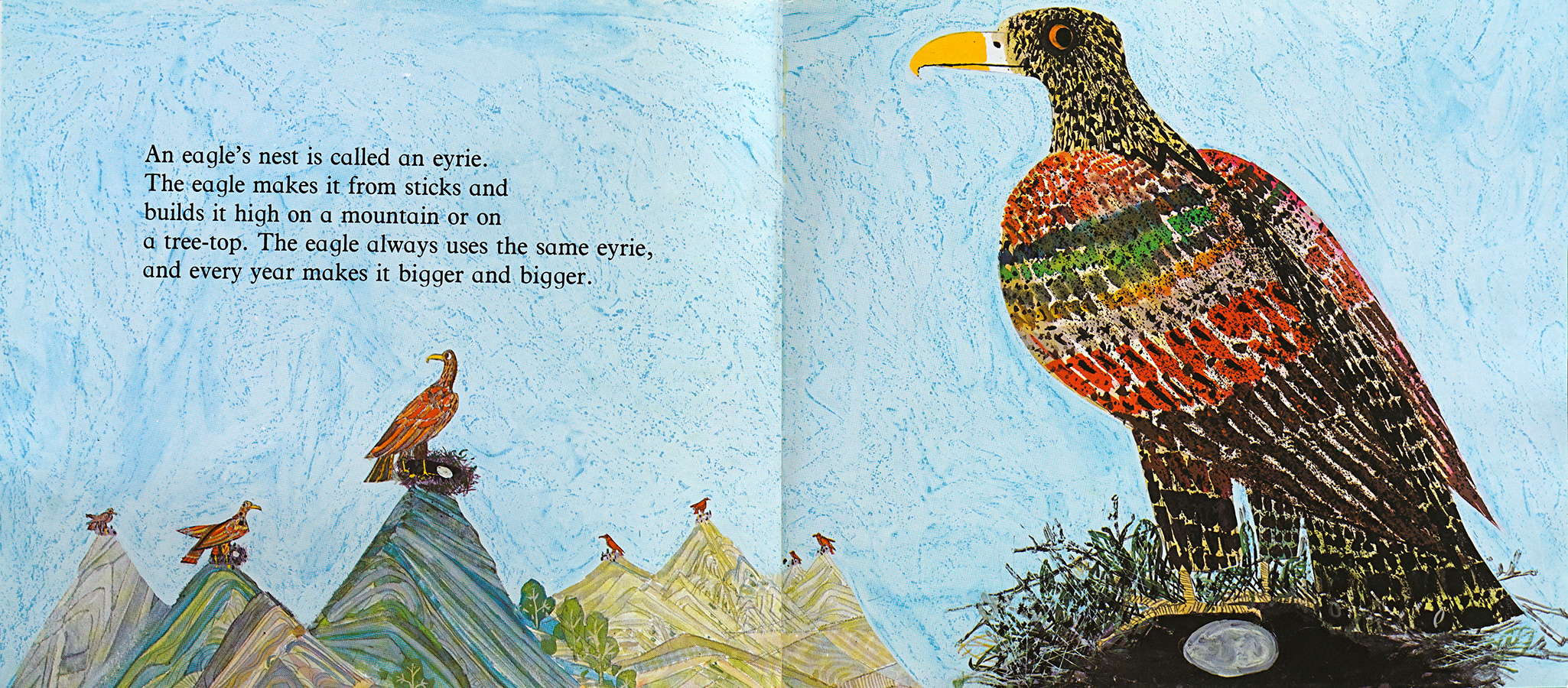

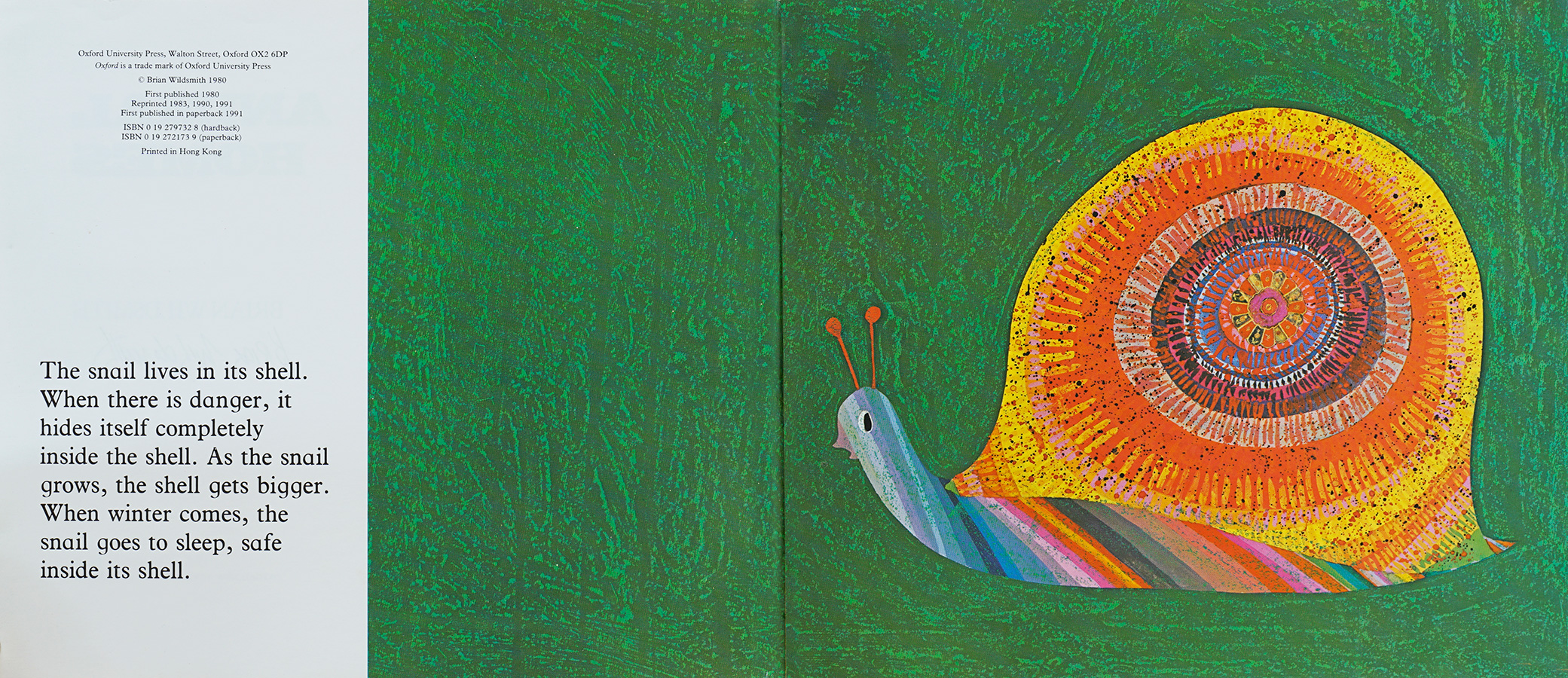

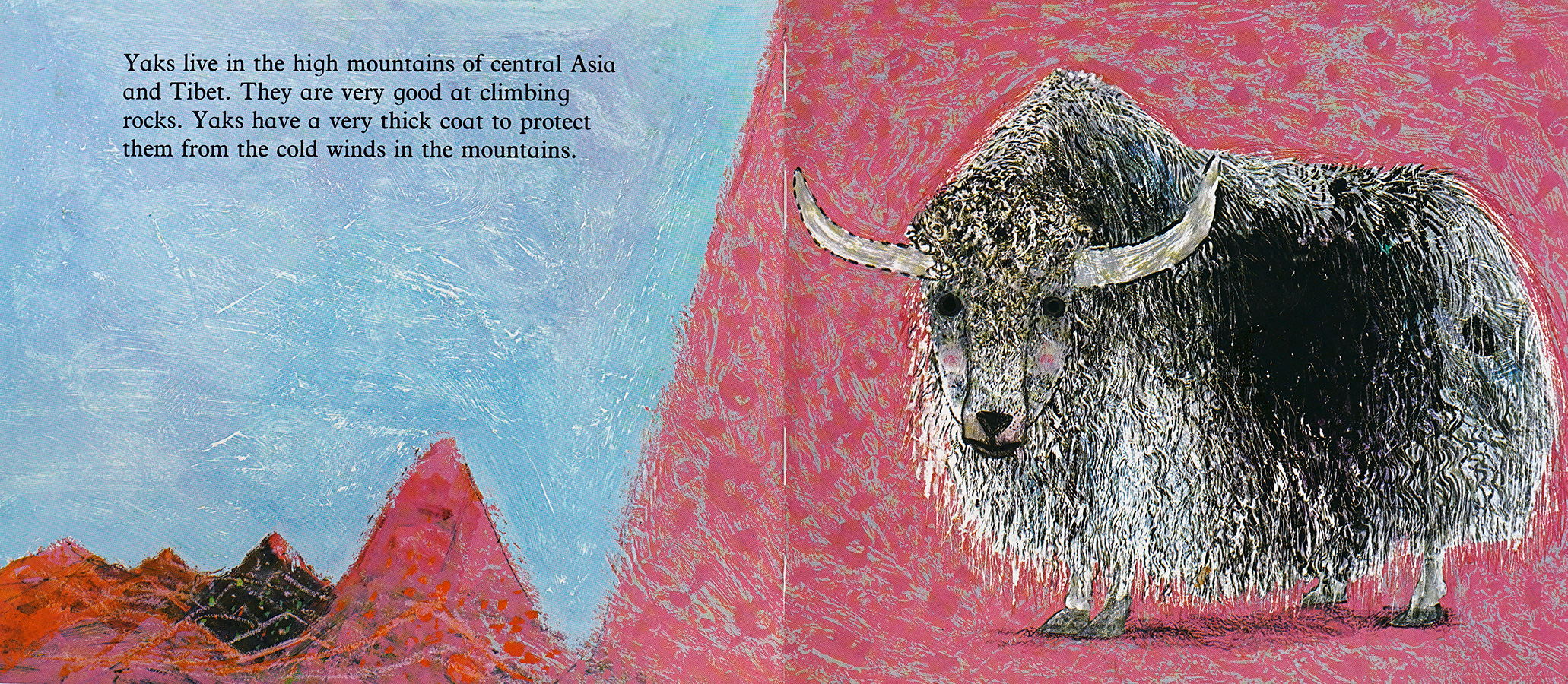

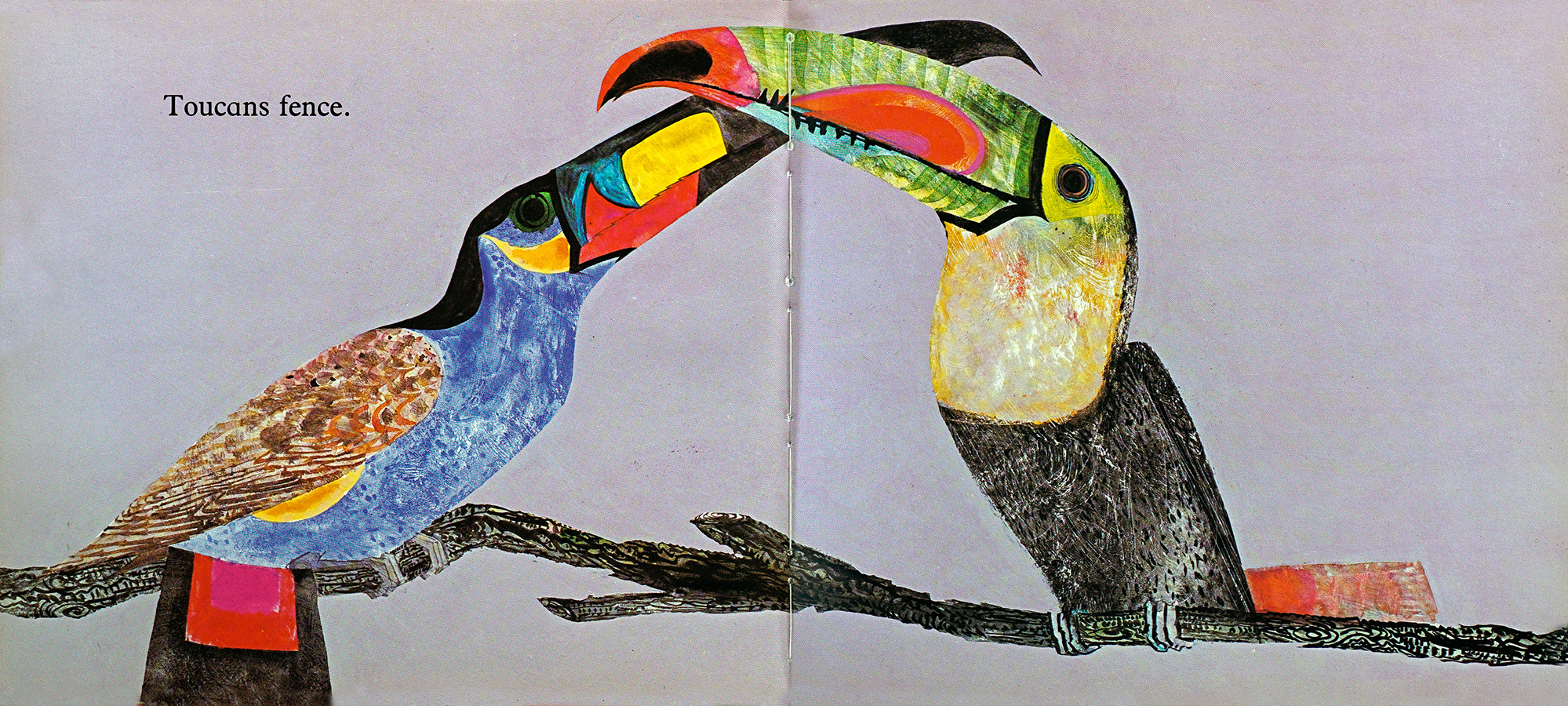

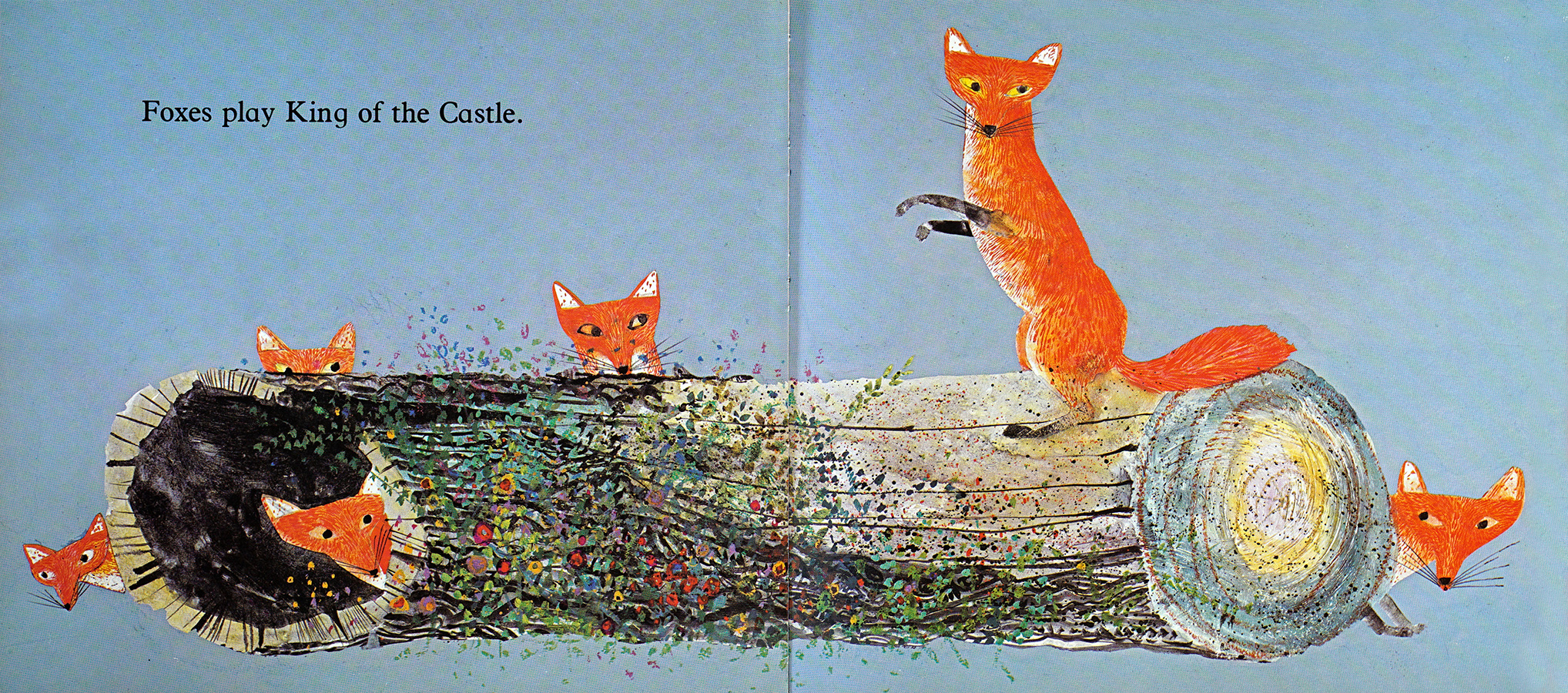

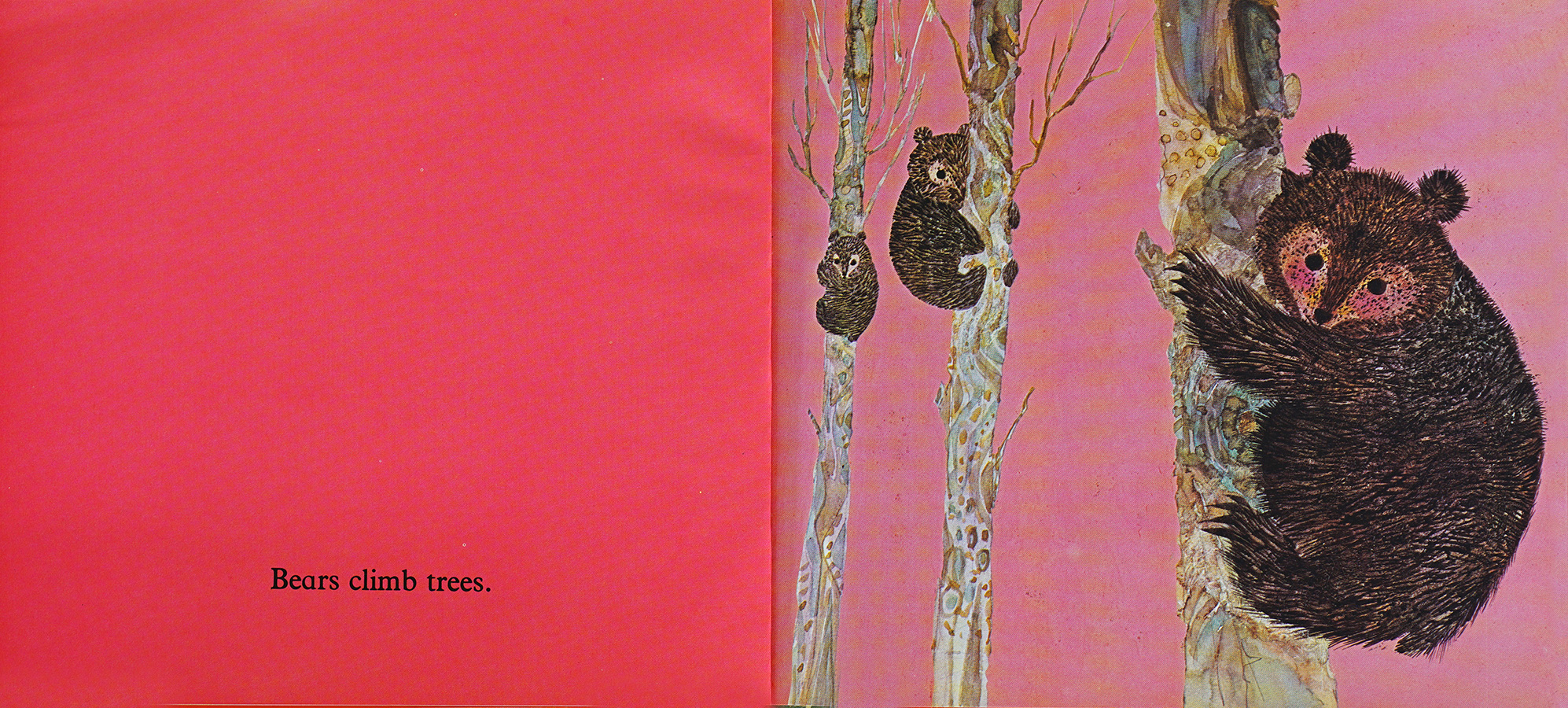

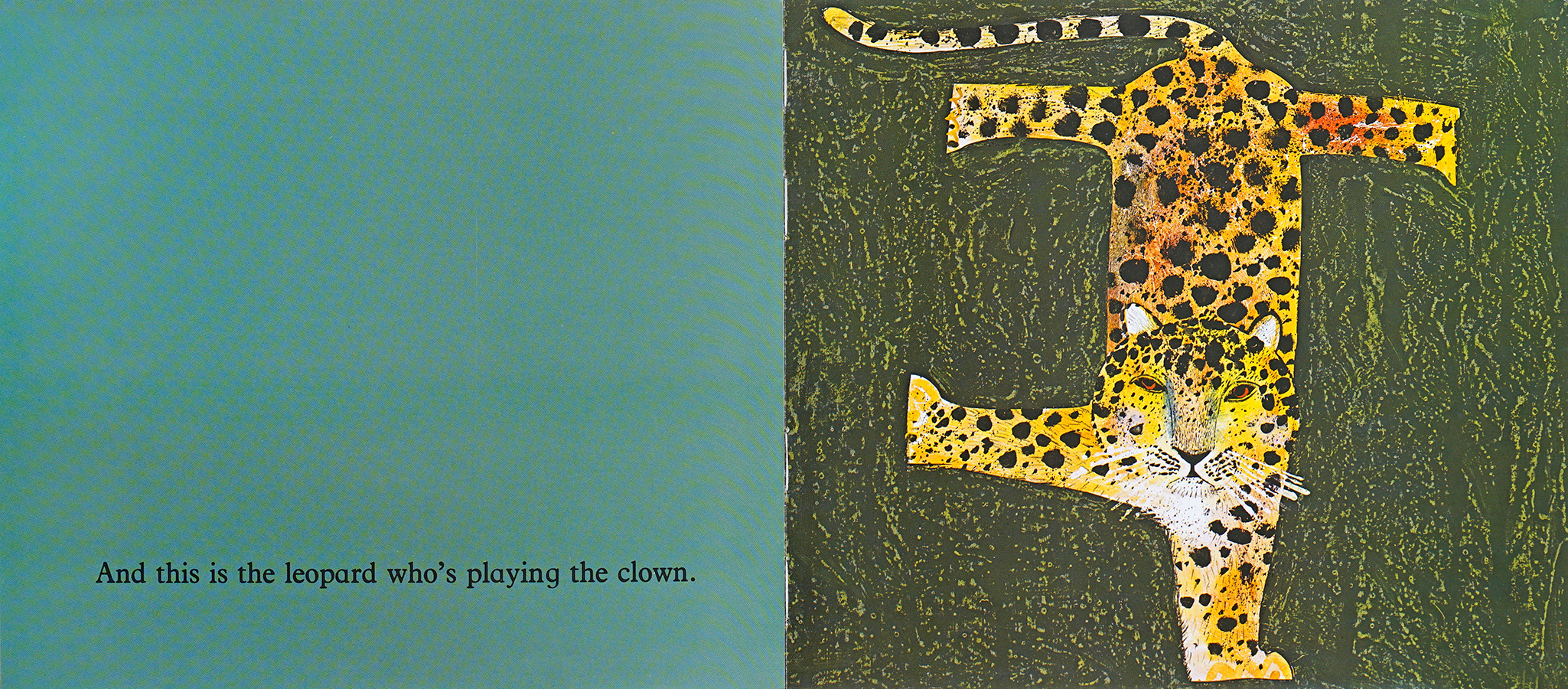

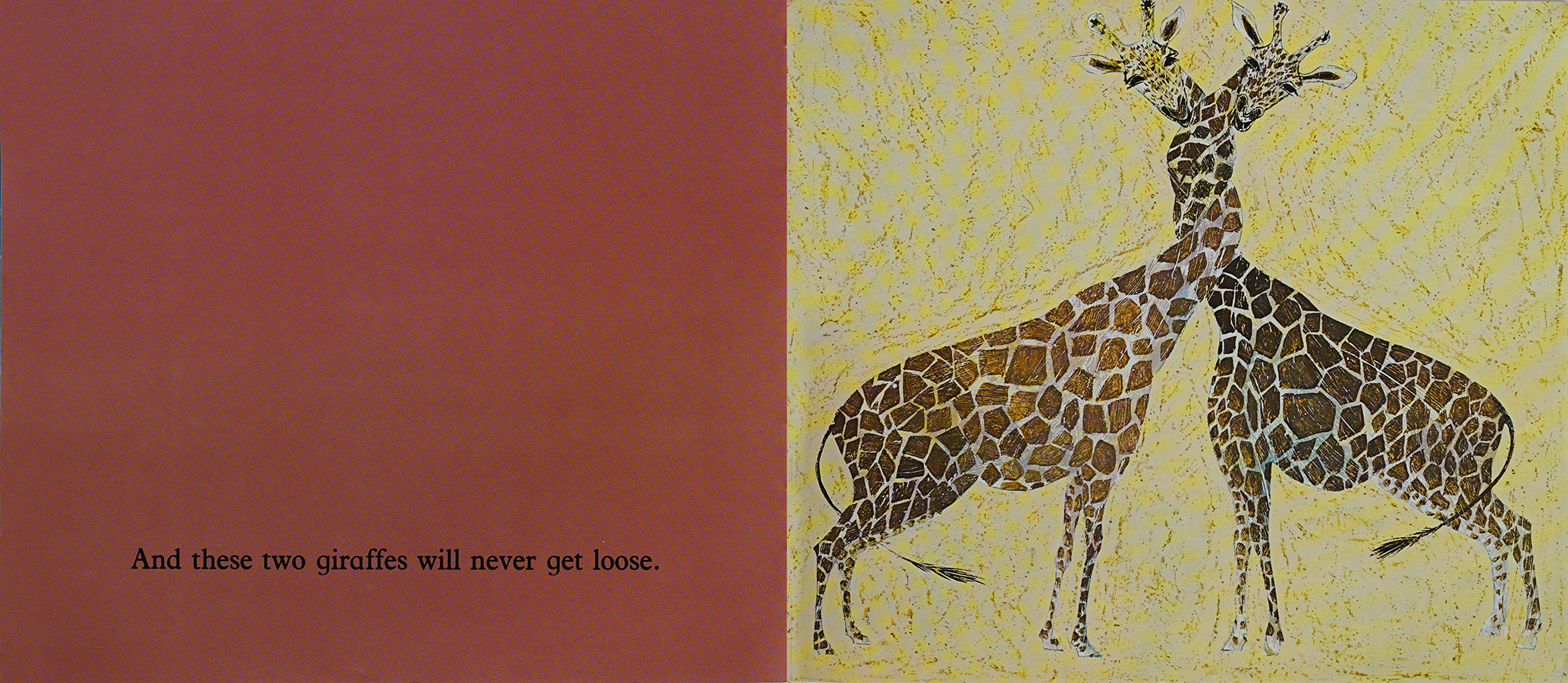

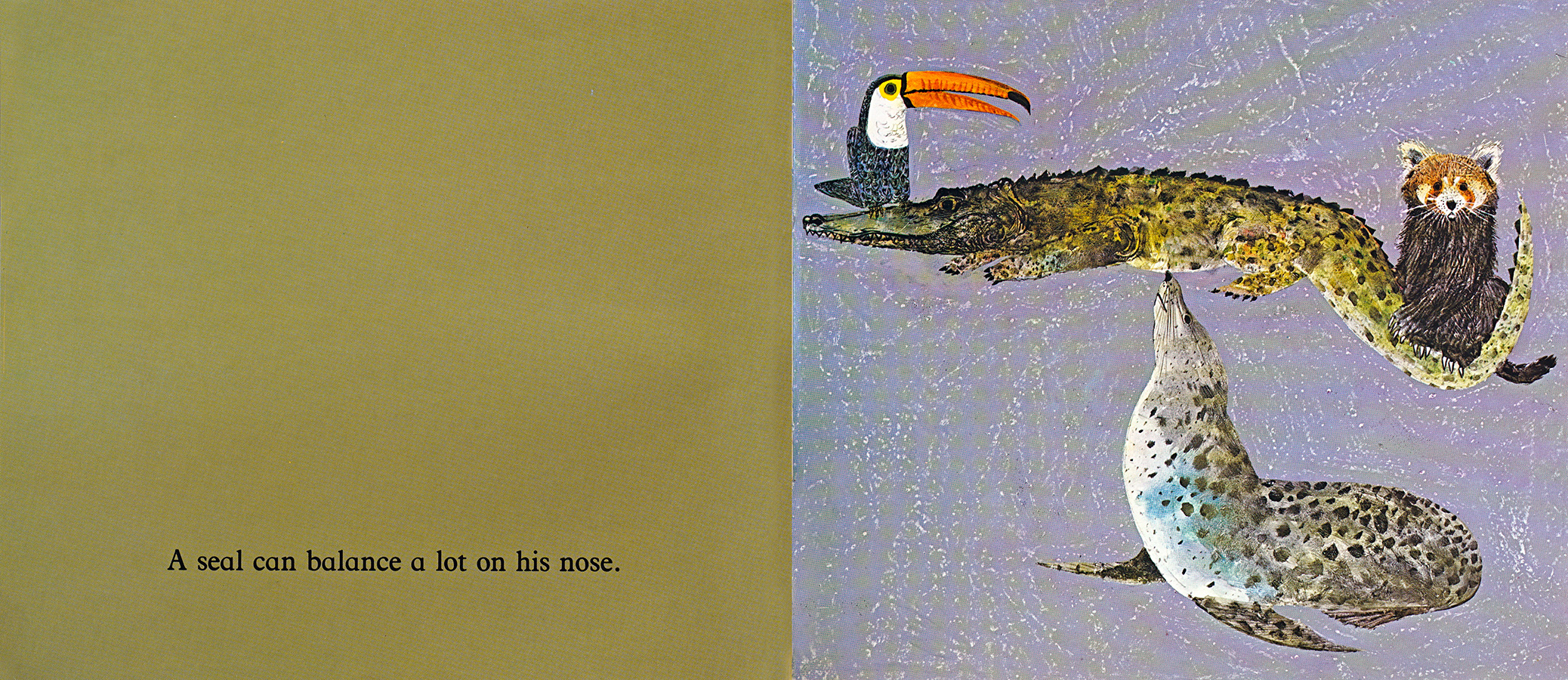

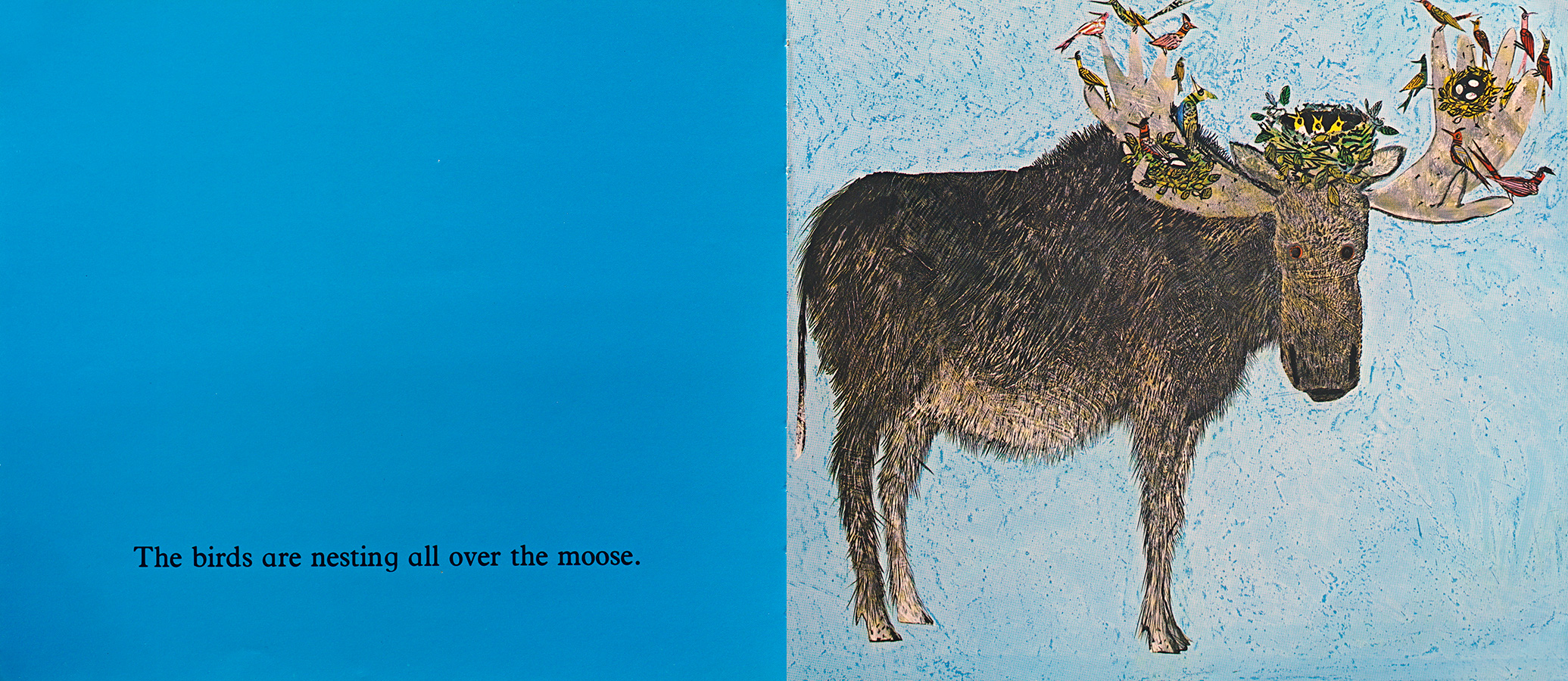

That same year, he completed five small concept books entitled: Animal Games, Animal Homes, Animal Shapes, Animal Seasons and Animal Tricks. “I like to use animals in my books, not only because they allow diversity of shape, colour and texture, but also for their allegorical function when representing human nature,” he said in one interview. The texts in this series are all very simple, at times in rhyming couplets and always accompanying self-explanatory, brilliantly-coloured paintings of animals either in their various habitats, playing games, going through their seasonal cycles… all in an attempt to encourage children to create their own stories or indeed, their own pictures.

Extracts from Animal Shapes, Animal Homes, Animal Seasons, Animal Shapes and Animal Tricks

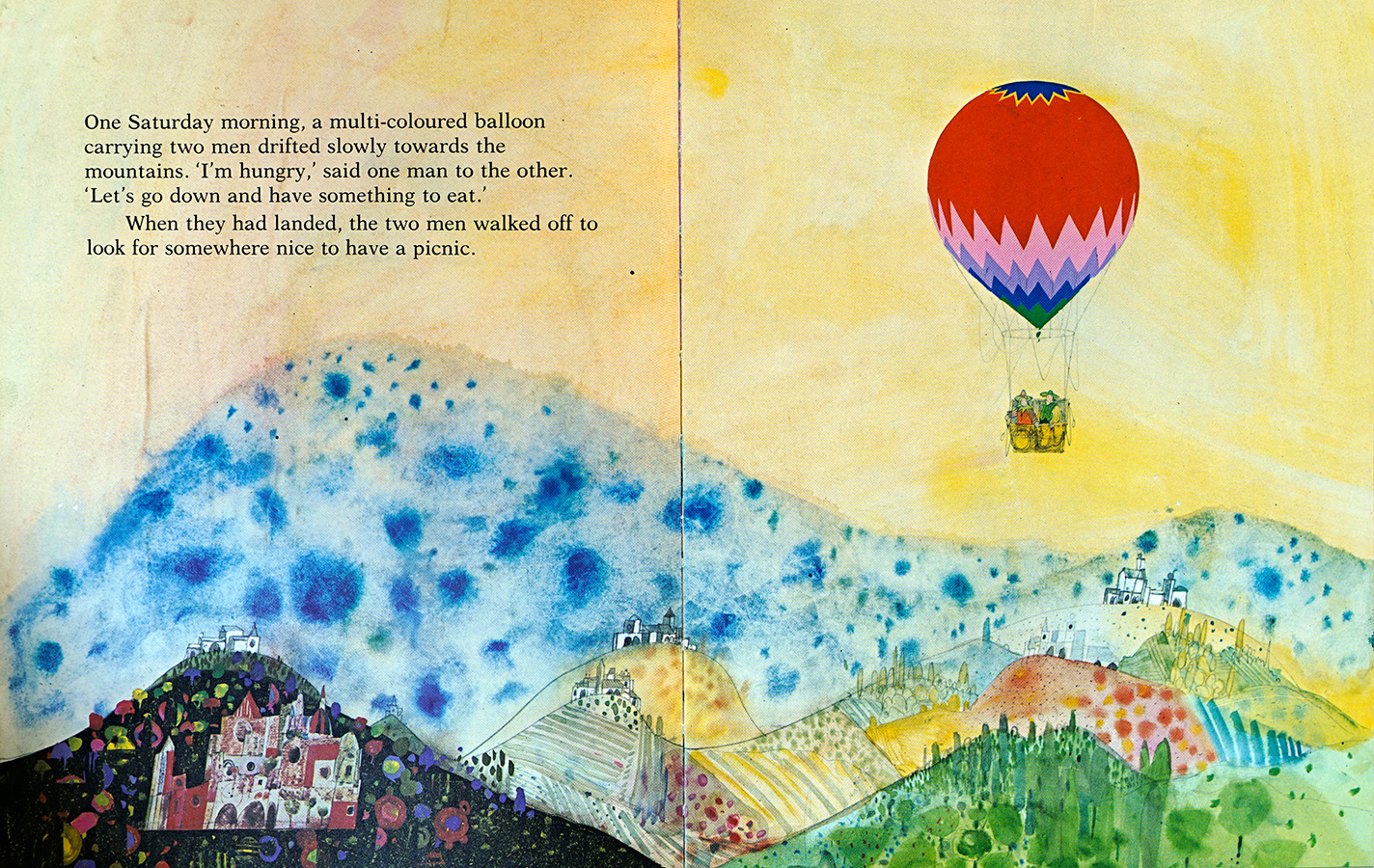

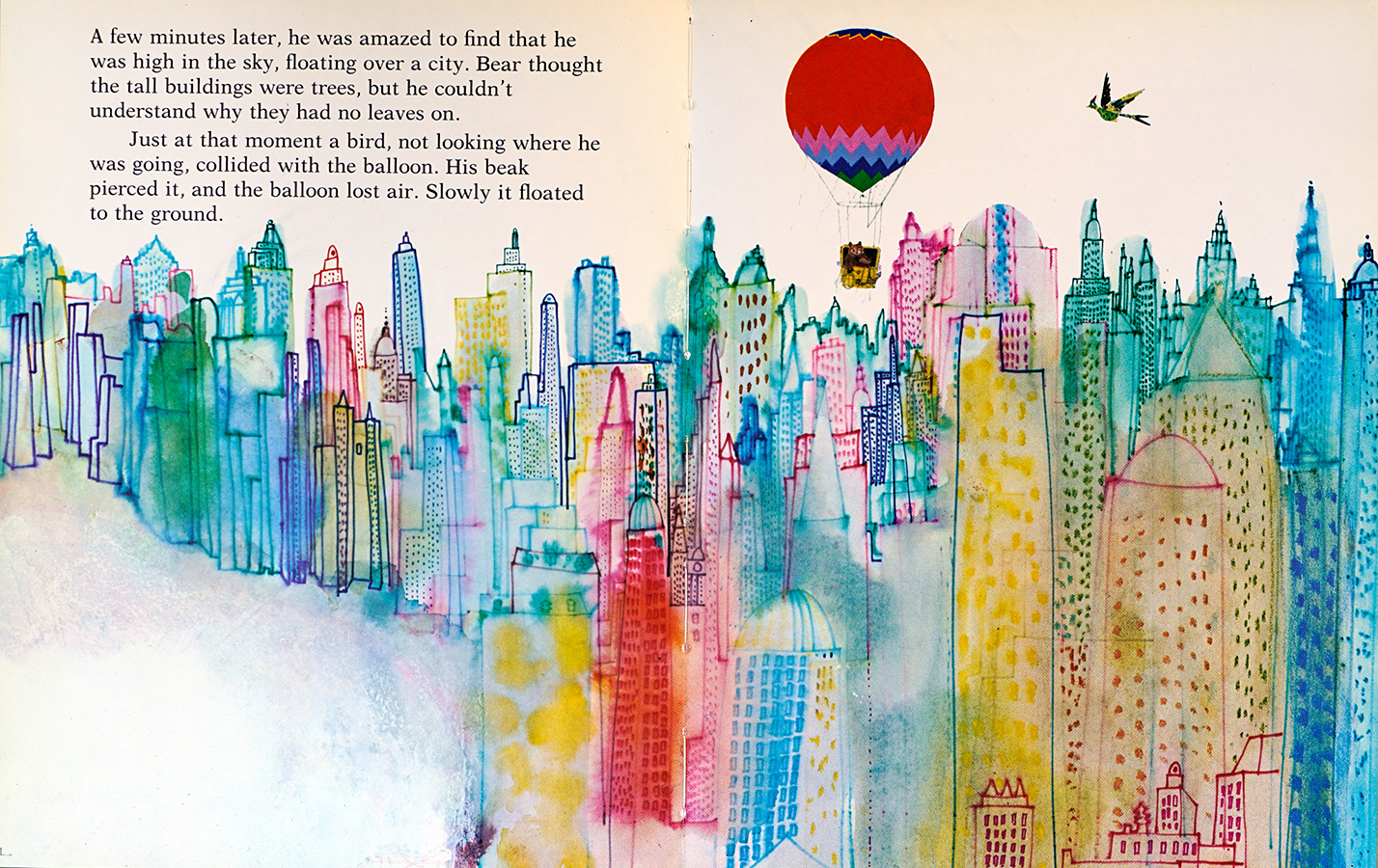

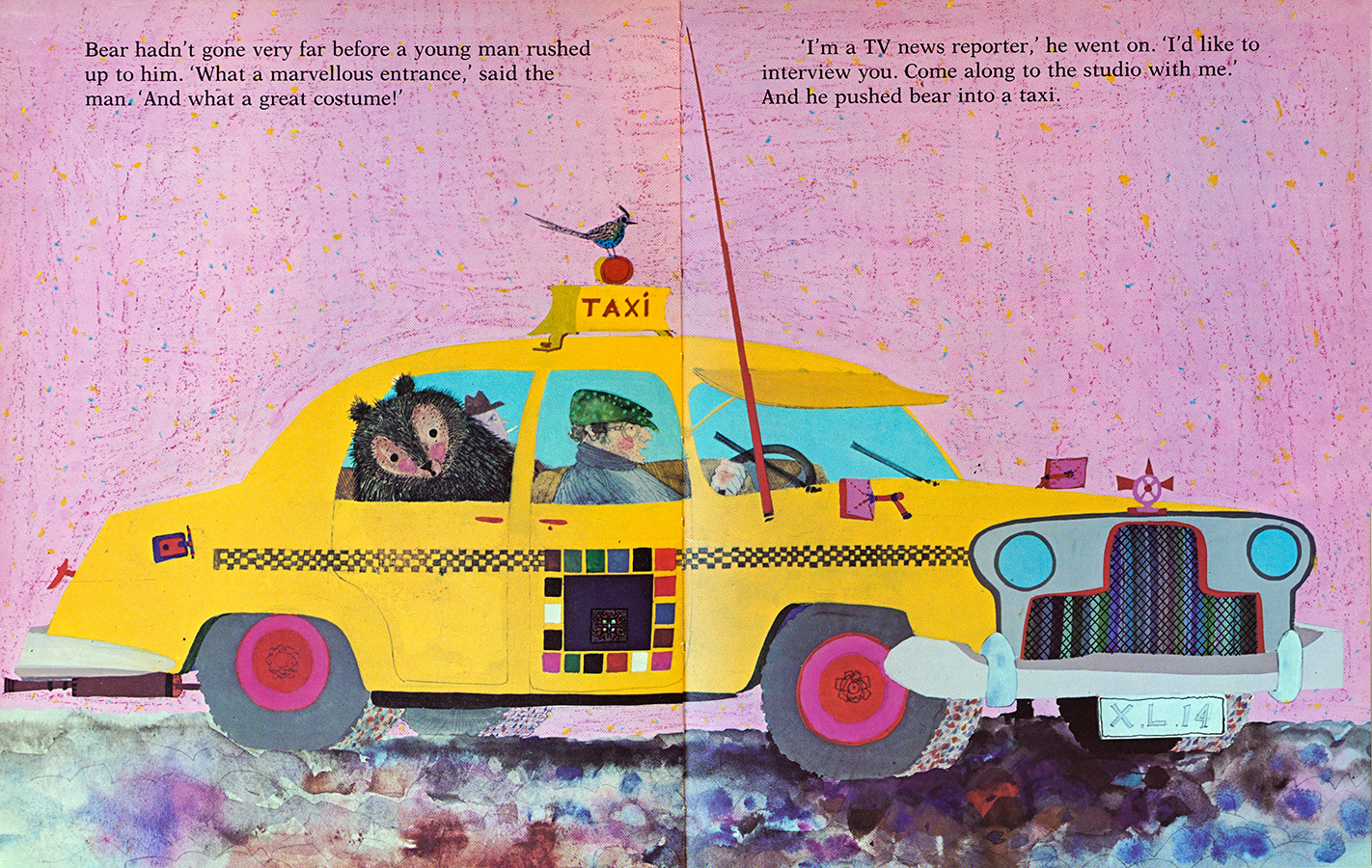

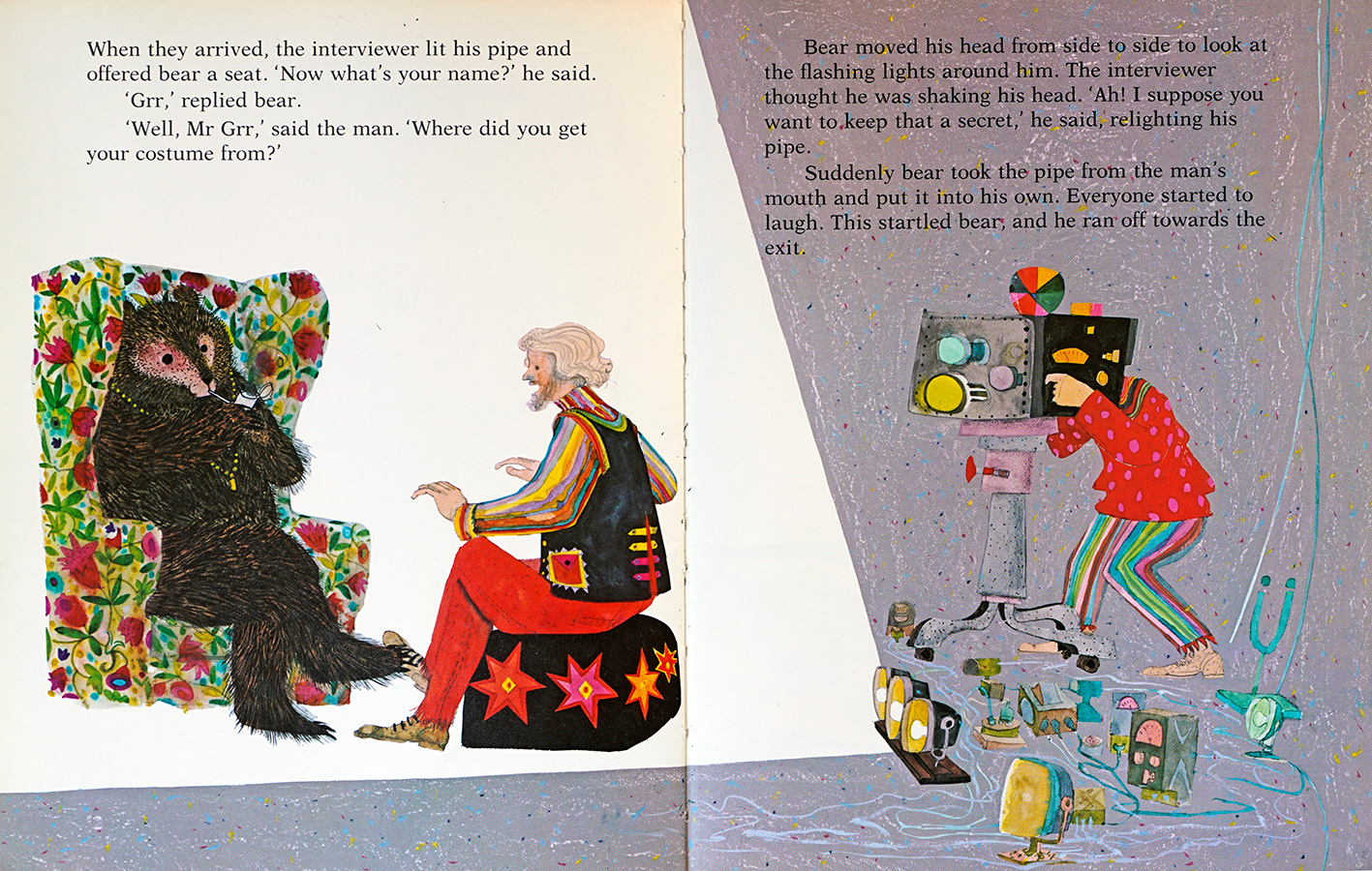

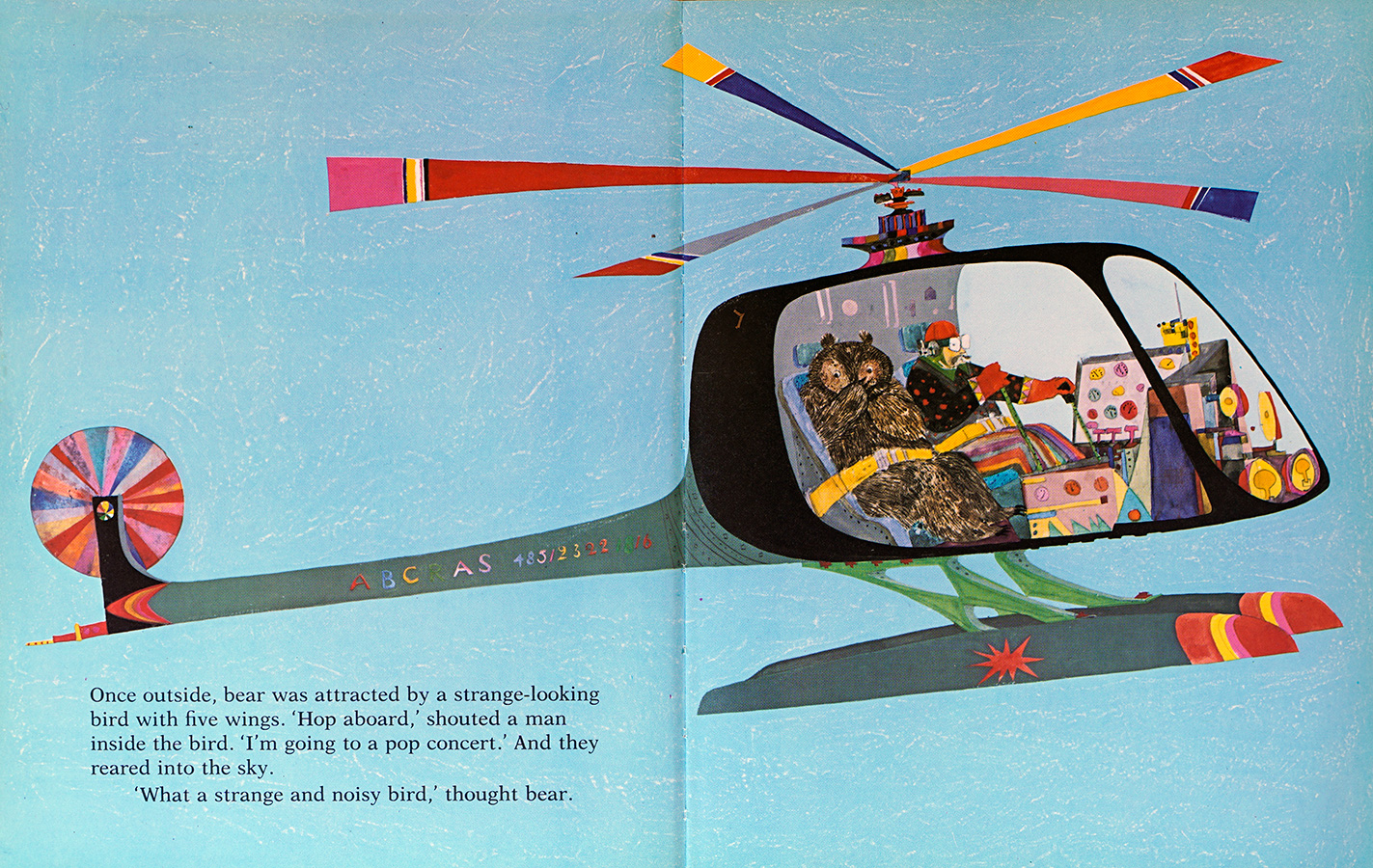

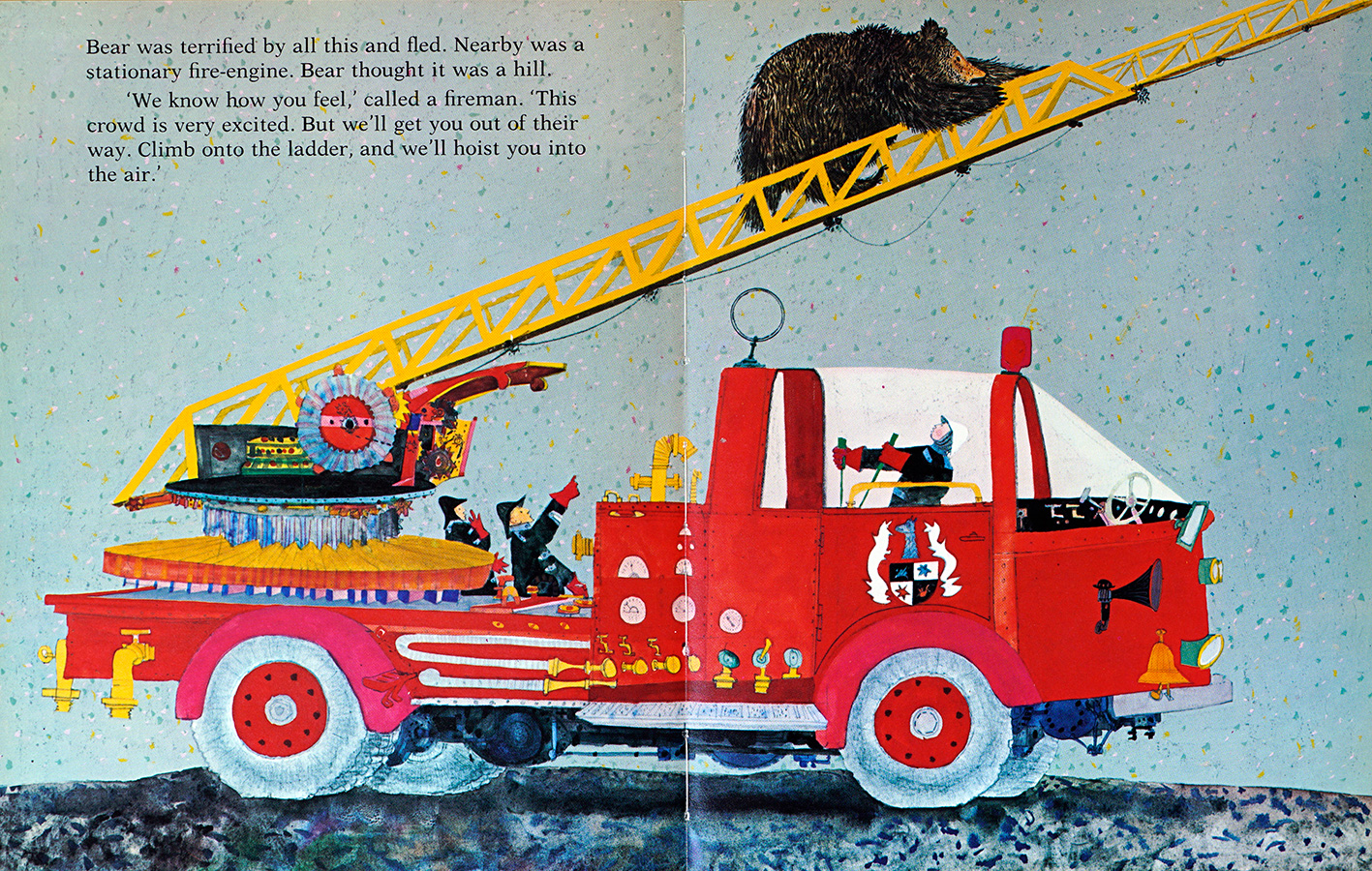

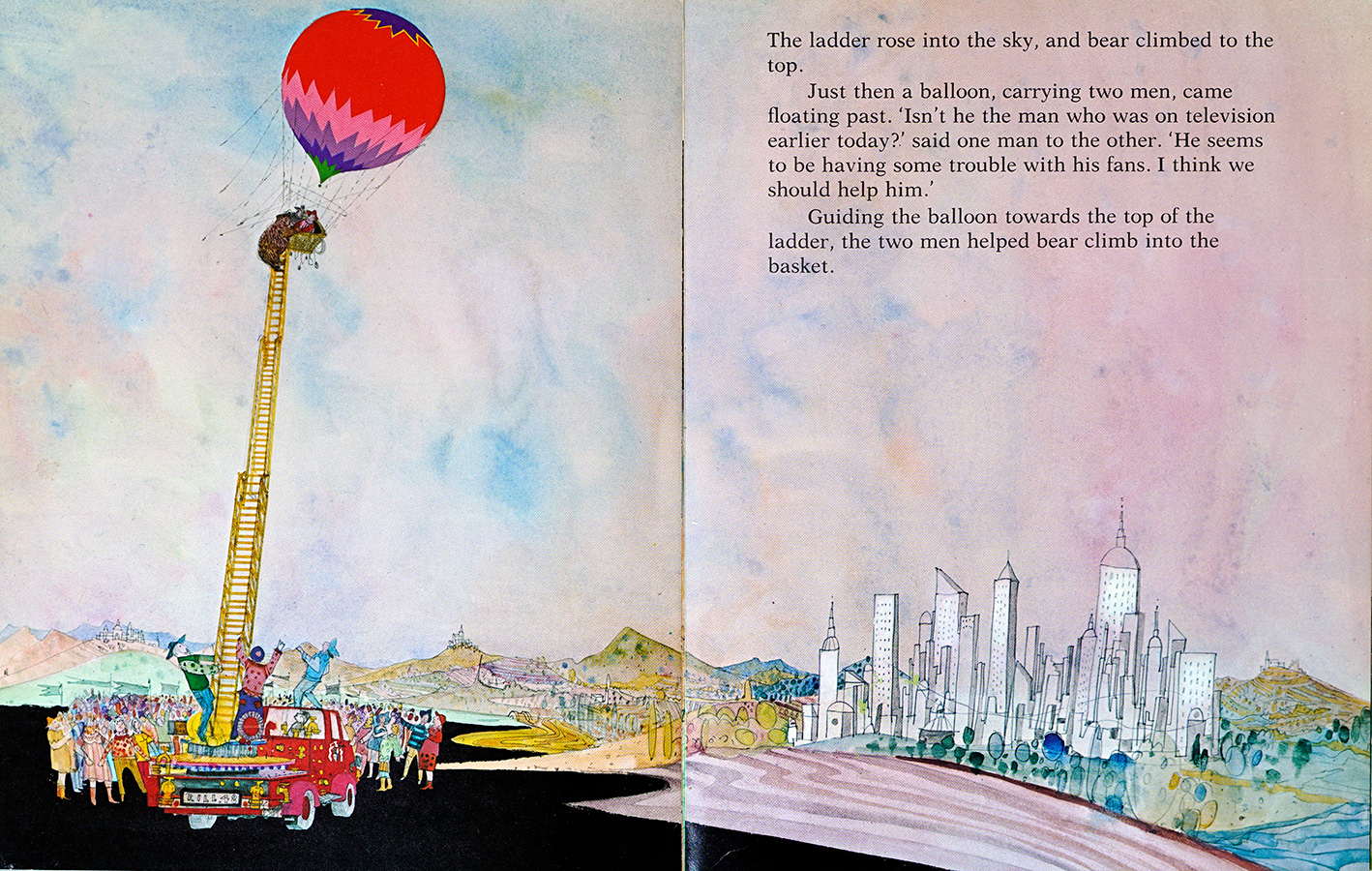

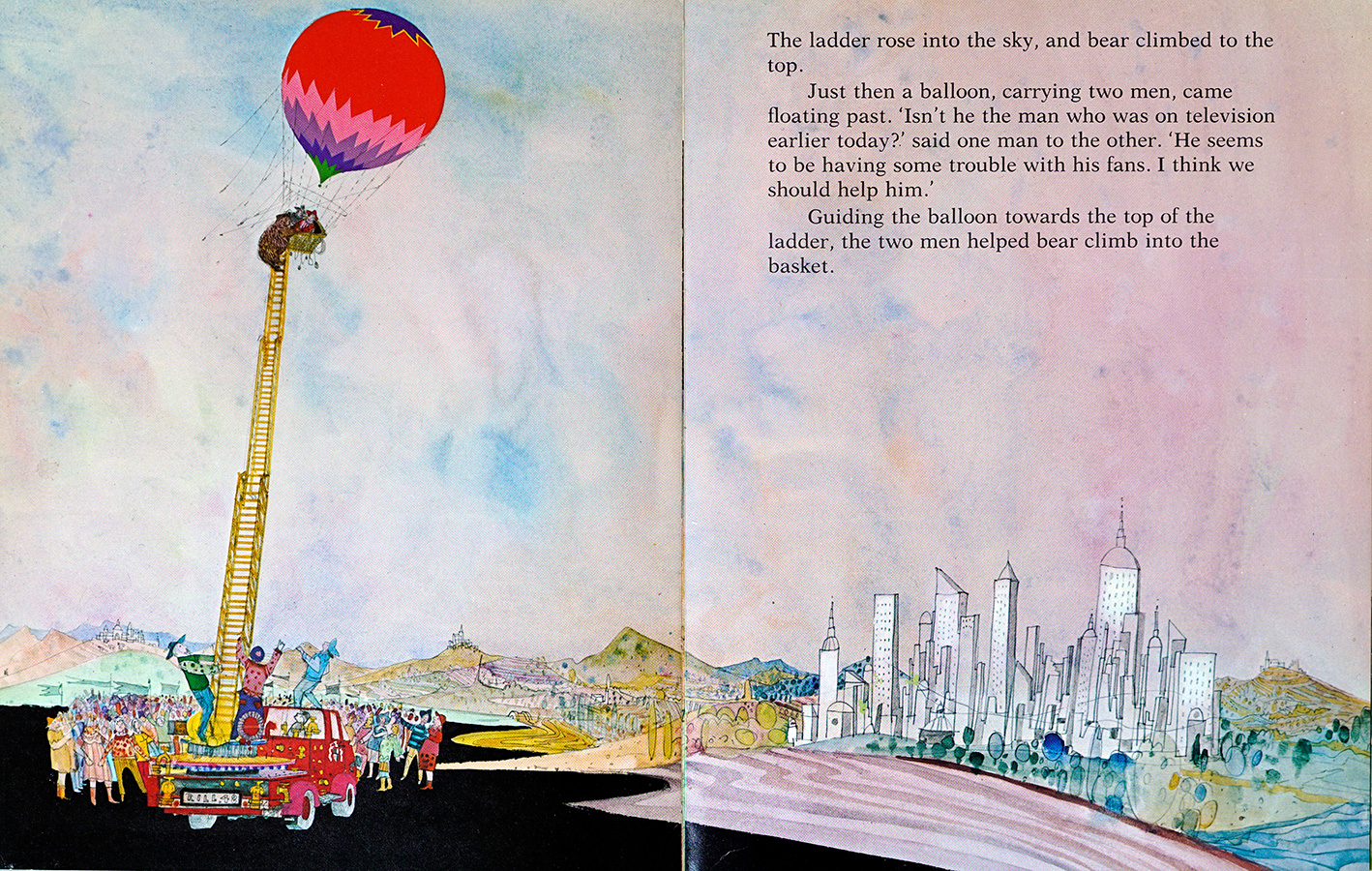

The following year, in 1981, Brian and Ron Heapy, the new Managing Children’s Editor at Oxford University Press, flew from London to visit the New York offices together. One evening, as they were strolling through the city, overwhelmed by its size, vibrancy and energy, Ron turned to Brian and exclaimed in an inquisitive manner, “What if a Wildsmith animal were to be let loose here?” This caught Brian’s attention and the result was Bear’s Adventure, a book of pure unadulterated fantasy and entertainment.

The two men respected one another both professionally and personally and became good friends, often lunching or dining together at Brian’s London club, The Reform. Brian loved this place for its central position on Pall Mall, its unique atmosphere, architectural beauty and a quite extraordinary library of some 75 000 books.

A book conceived in New York where Bear has one hell of an Adventure! Now published by Star Bright Books.

The Reform Club lobby from above, with a waiter carrying a tray of drinks drawn from the first floor mezzanine by Rebecca Wildsmith in her tiny picture diary.

BACK TO LONDON

Later in life, the Reform Club would become his home away from home. It was in London in fact that he worked on Bear’s Adventure, since a number of issues involving most notably his two youngest children, had led to a return to live there. Unlike our mother, who was unquestionably delighted to be back in the country she loved and a city full of familiarity and stimulation, Brian was less pleased. Clare, the eldest was old enough to be left at university in Nice to read sociology. Rebecca decided to do an art foundation course in London at the Byam Shaw School of Art, while Anna was sent to the French Lycée in South Kensington. Simon needed some proper old boarding school discipline and was packed off to the chilly depths of northern Scotland. From Cannes to the Cairngorms… Youpee!

In the summer of 1982, Oxford University Press, South Africa, invited Brian to participate in the East London Book Fair to be held from the 10th - 21st August. Before the numerous talks he was scheduled to give to teachers, librarians and hundreds of school children, he was interviewed by Margaret Williamson. She was literally literally “awe-struck” by the fact she was about to meet “the world’s leading illustrator of children’s books.” Upon meeting him, she was especially taken by his “vibrant personality.” In her article she wrote, “Brian is like his books, full of colour. He has smiling eyes and charm that washes round you warmly, making you feel like a friend.” The extremely sympathetic welcome he received from the South African community was confirmed by his receiving an avalanche of thank-you letters upon his return to France.

The following piece is from one of them, sent by Evelyn Rossmeis, a librarian and pre-school teacher. It sums up the general consensus: “My colleagues and I found Mr Wildsmith so much in tune with children and so obviously endowed with empathy that is inborn, not taught. He was so enthusiastic that we are still riding the wave of excitement that was generated at his talk and enhanced by his rapport with the audience.”

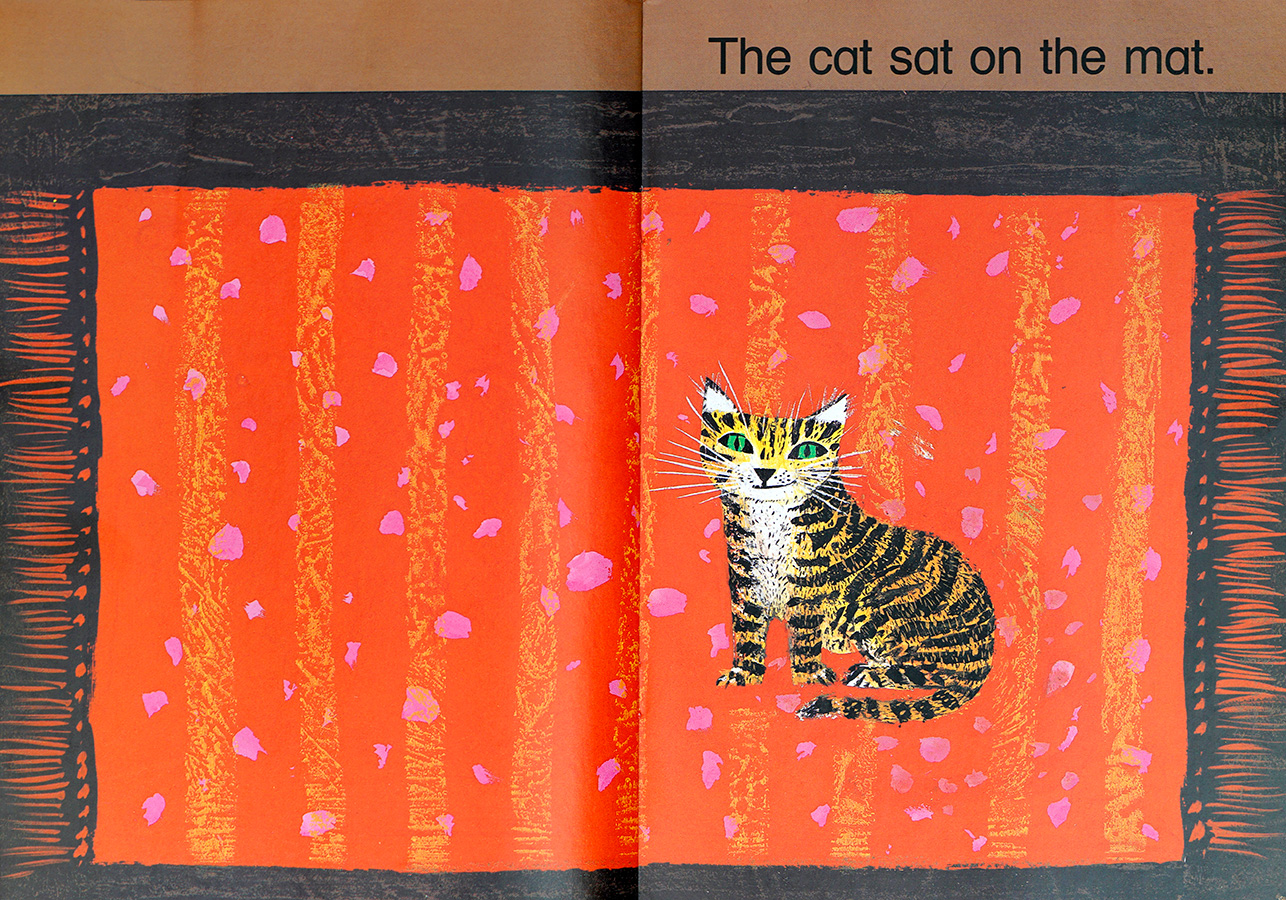

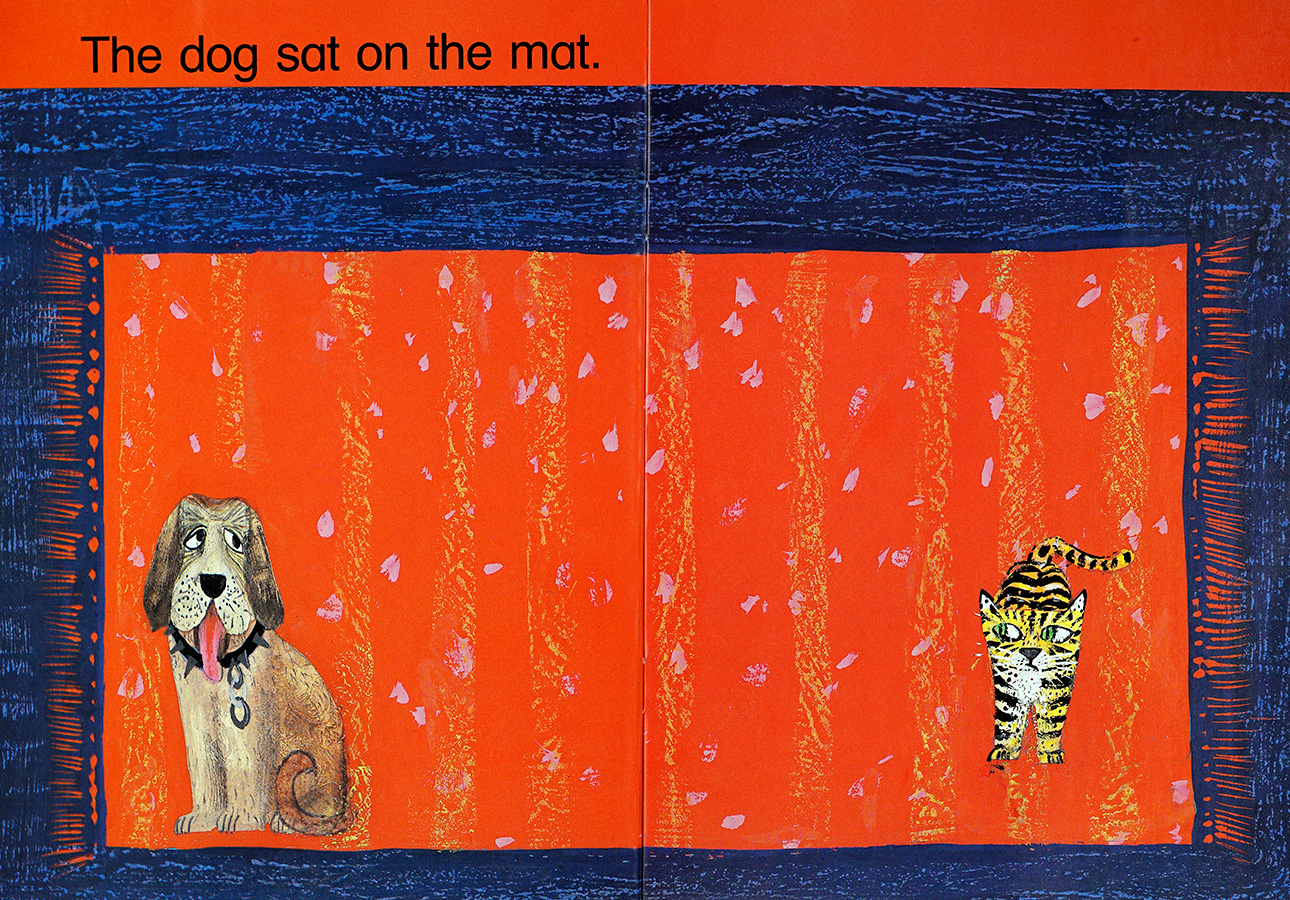

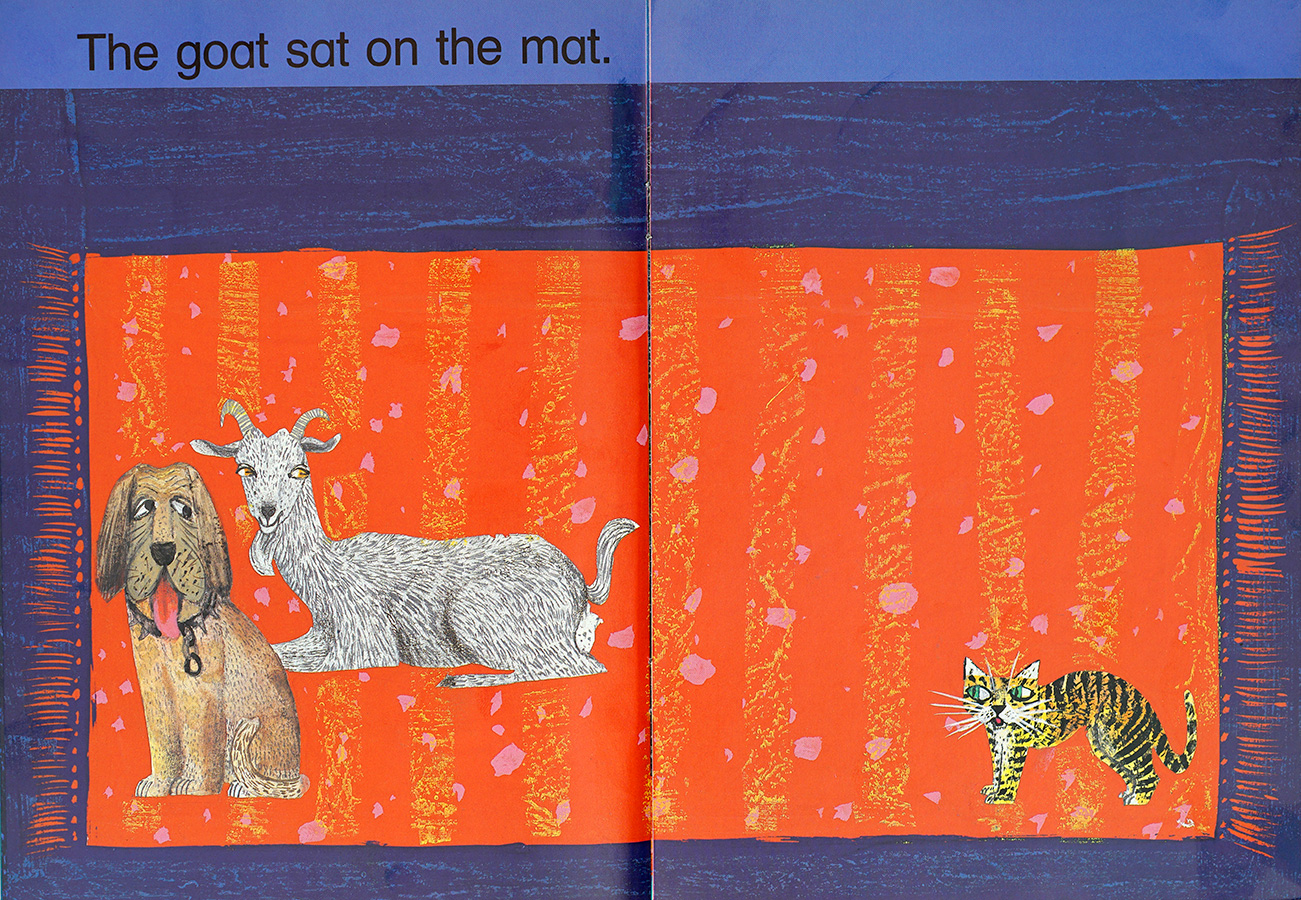

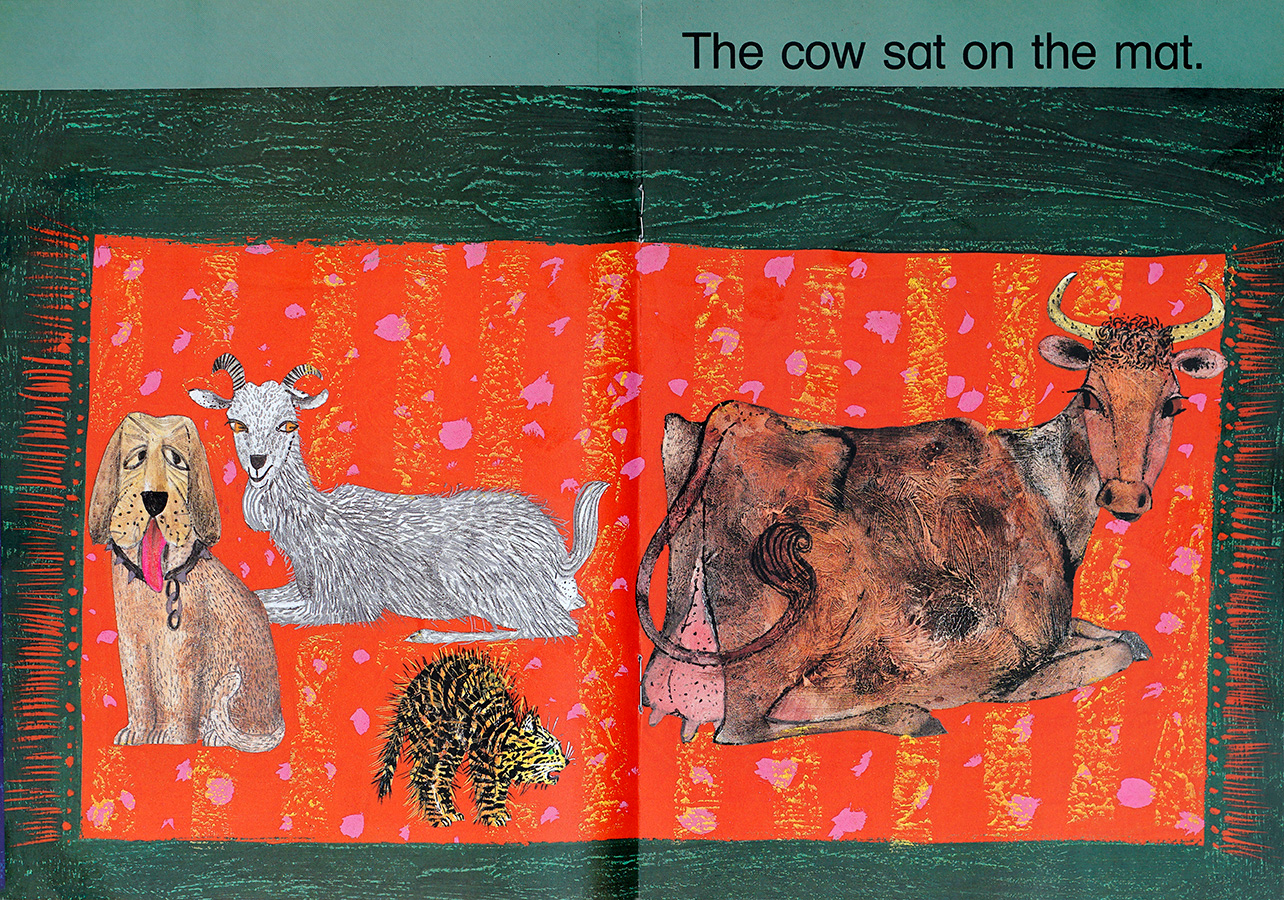

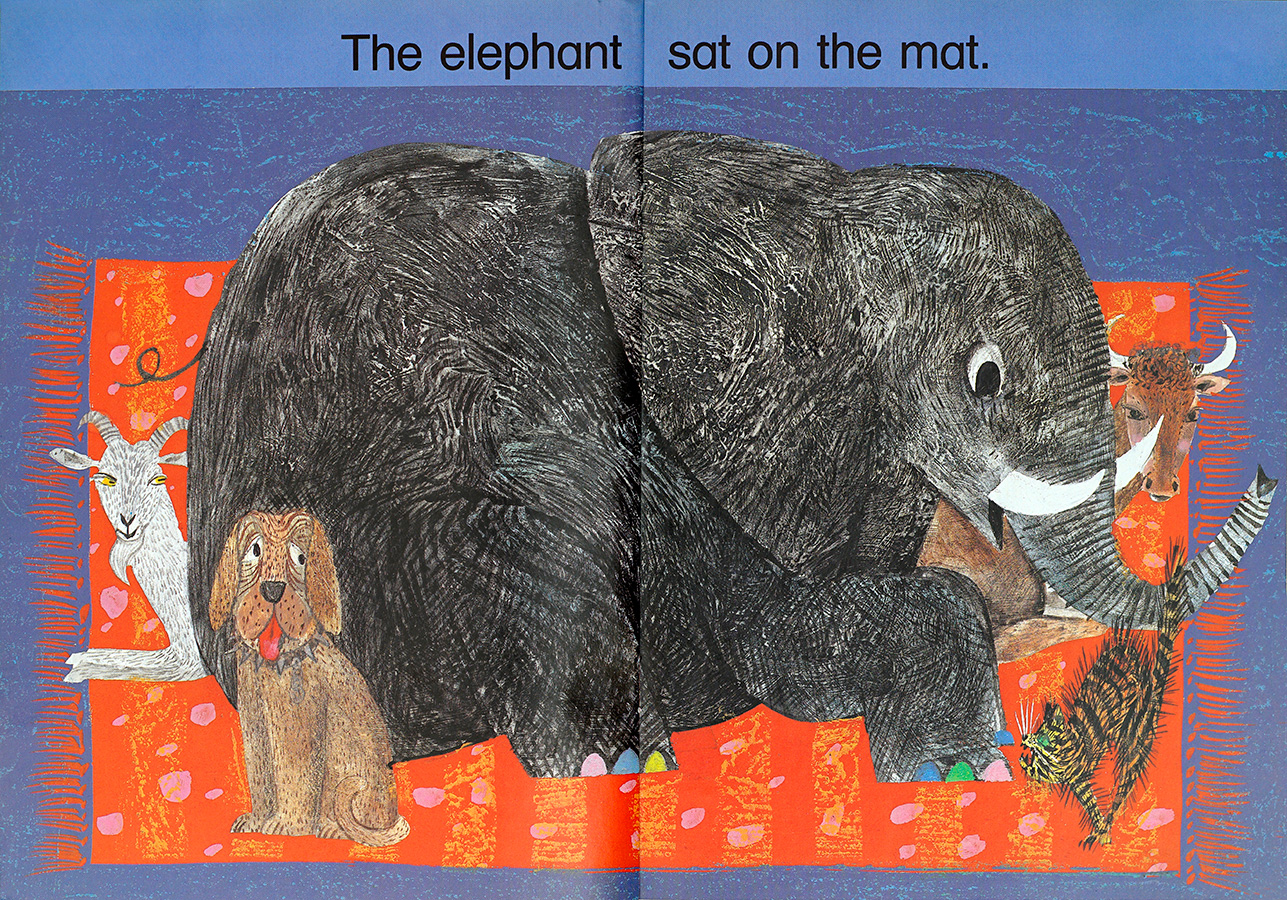

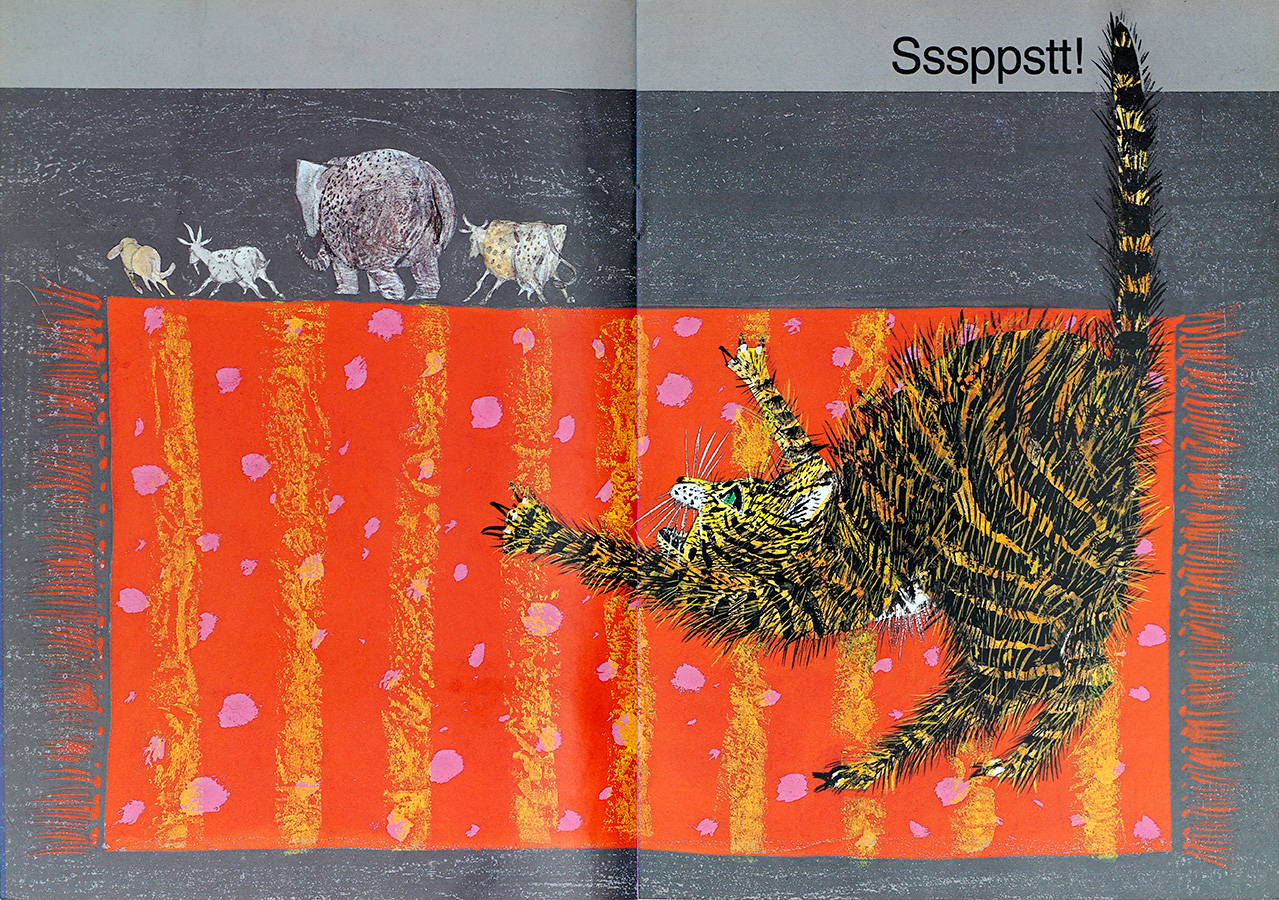

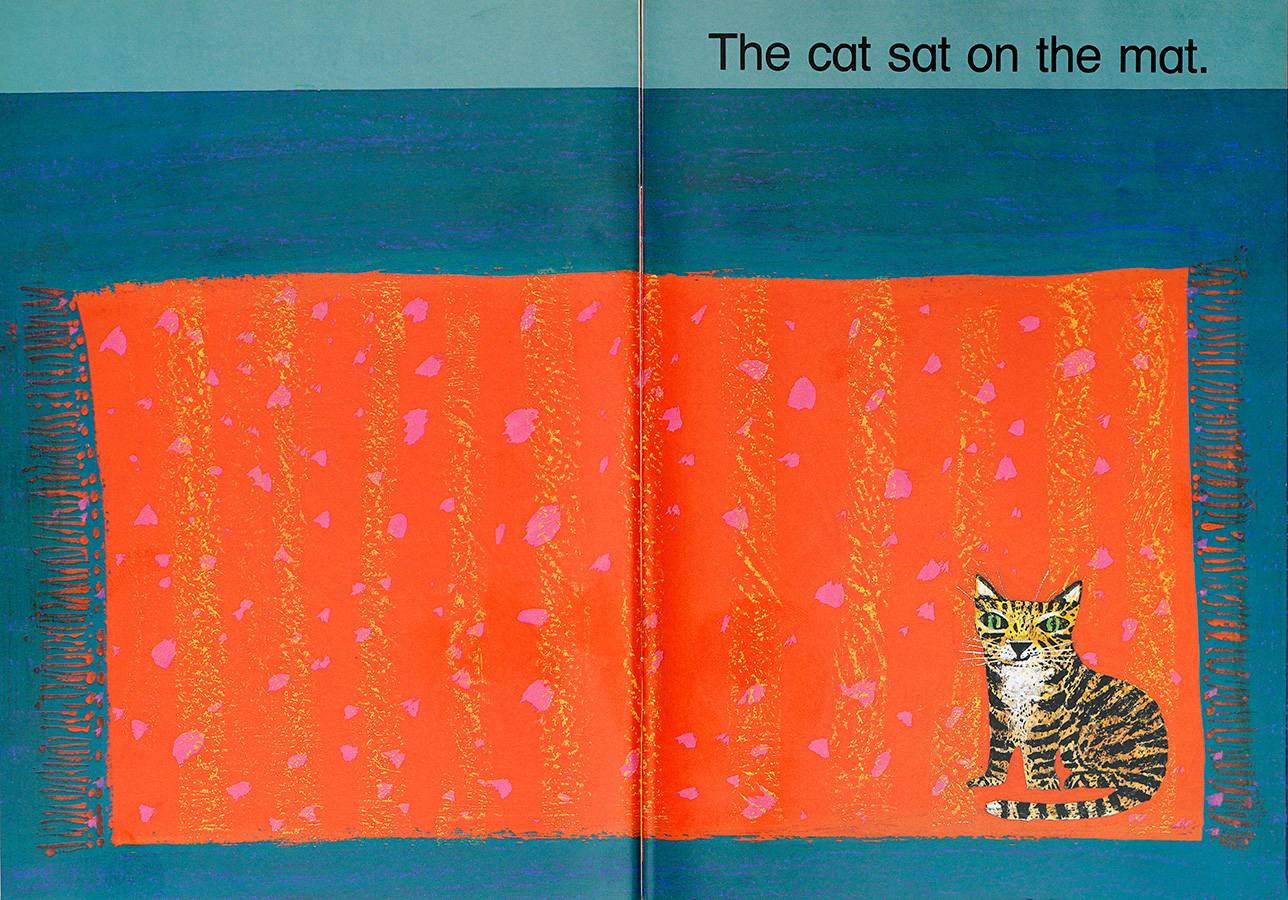

Later on that year and on and off for the next 18 years, Brian embarked on the project of creating a series of 17 simple books for very young children. Amongst his professional correspondence, we found a letter in which he explains what inspired the first of these: “I had arranged to meet my editor Ron Heapy in Paris to discuss plans for future book projects. To be honest I didn’t have any ideas as I approached the 16th century hotel where we had planned to stay, and there, sitting in the hotel doorway on a mat, was a cat. He was furious when I stepped on his domain, refusing to move out of my way, his back arched, spitting his annoyance at me. Later, as I sat in my room waiting for Ron, desperately trying to think of an idea for a book, I thought of that cat sitting on that mat and… there it was… the old adage, the cat sat on the mat. The rest just followed suite. I was saved! The pictures would have humour and a repetitive text, perfect for what became the first of a series of small books: simple, humorous situations with short, easy to read texts, in keeping with my belief of what should be the essence of a book for very young children.”

The idea for the best selling Cat on the Mat book came to Brian in extremis, thanks to a rather territorial cat’s behaviour on the mat in front of the hotel he was staying at in Paris in 1982.

According to The British Book News they “provide some of the best narrative structures and forms in miniature for children's earliest reading experiences.” They were: Cat on the Mat and The Trunk in 1982, All Fall Down, The Nest, The Apple Bird and The Island in 1983, Toot, Toot and Whose Shoes? in 1984, Giddy Up, If I Were You, My Dream and What a Tale in 1987 and finally Can You Do This? How Many? If Only, Knock, Knock, My Flower and Not Here in 2000, all part of The Oxford Reading Tree series.

“Stunning illustrations and simple, easy to follow storylines, perfect for beginner readers and younger established ones too,” commented one school teacher. Writing in Books for Children, Margaret Carter called The Island “A small masterpiece.”

Almost 30 years after their first publication, Oxford University Press decided, in 2011, to compile material from these books in, Cat on the Mat and Friends. This marketing strategy was obviously well designed as over half a million copies have been sold to date. It is, according to the trade magazine, Growing Point, “A gloriously bright, lusciously coloured, dramatically conceived book for very young children to brood over.”

“This is an absolute joy to read aloud and the simple yet engaging text coupled with the vivid, humorous illustrations make it perfect for toddlers. Having sold half a million copies already, the book will bring delight to a whole host of new readers.”

The Book Seller

BY BLINDLY FOLLOWING LEADERS, ONE CAN EASILY BE LED INTO MISFORTUNE

The idea of using the split-page technique also came from Ron Heapy, who was intent on contributing towards the making of great books from the best ingredients. Three books were produced which exploit this simple yet ingenious format, designed to add narrative flow: Pelican, 1982, Daisy, 1984 and Give a Dog a Bone, 1985. They required precise craftsmanship both from the artist and the binder for this innovative technique to work. The illustrations had to be superimposed in such a way that the pictures, produced on each side of the page, align with hairline precision.

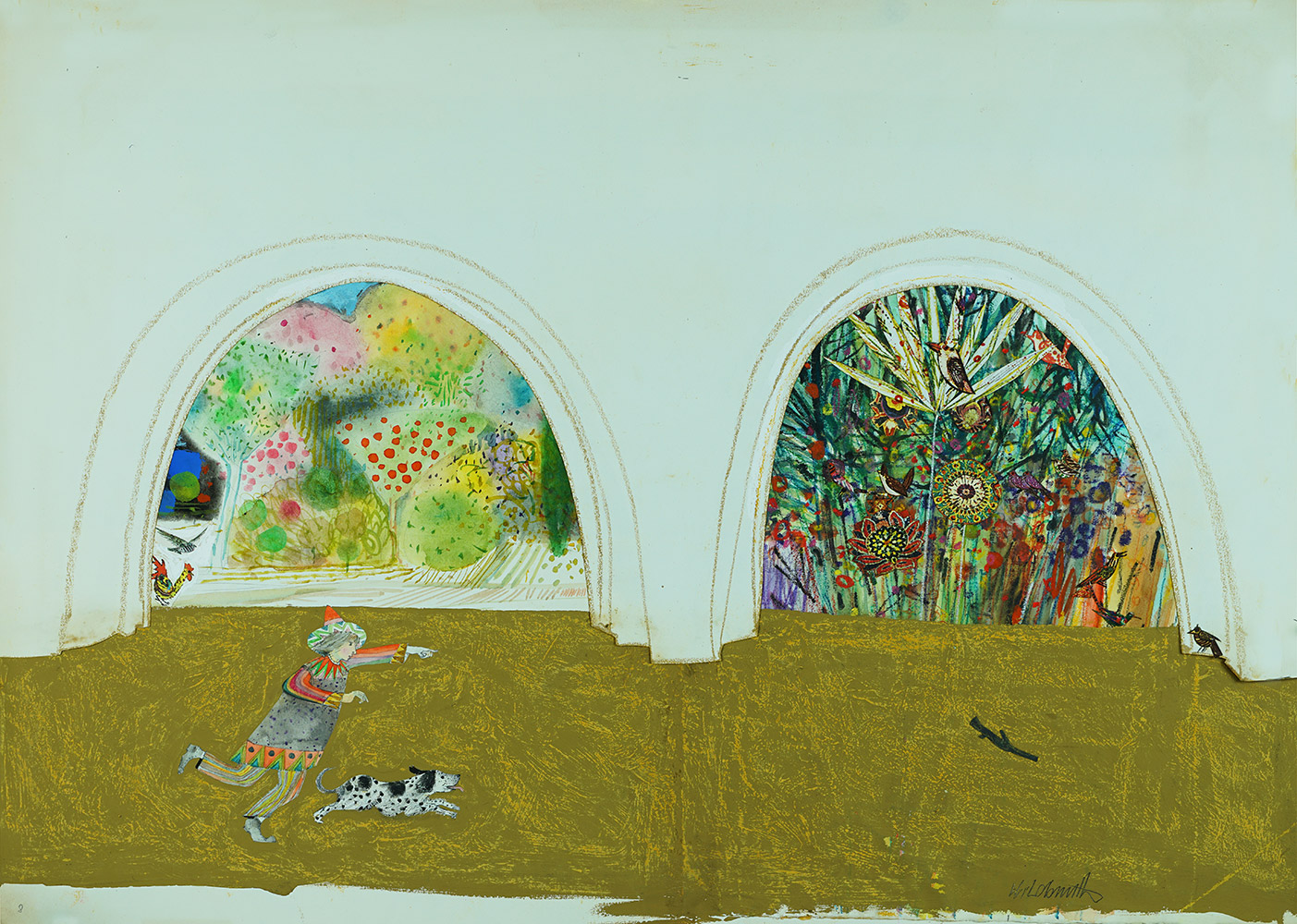

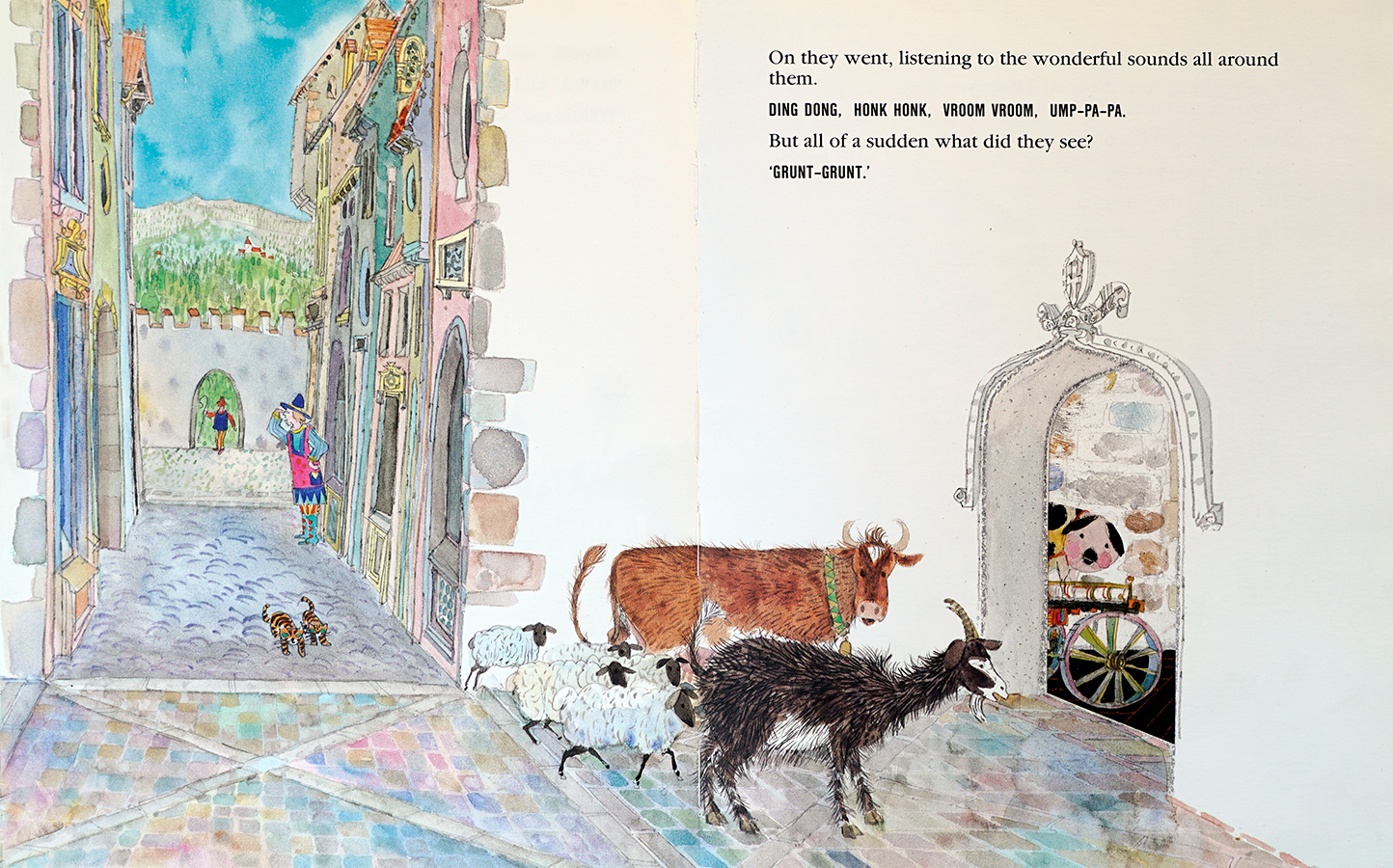

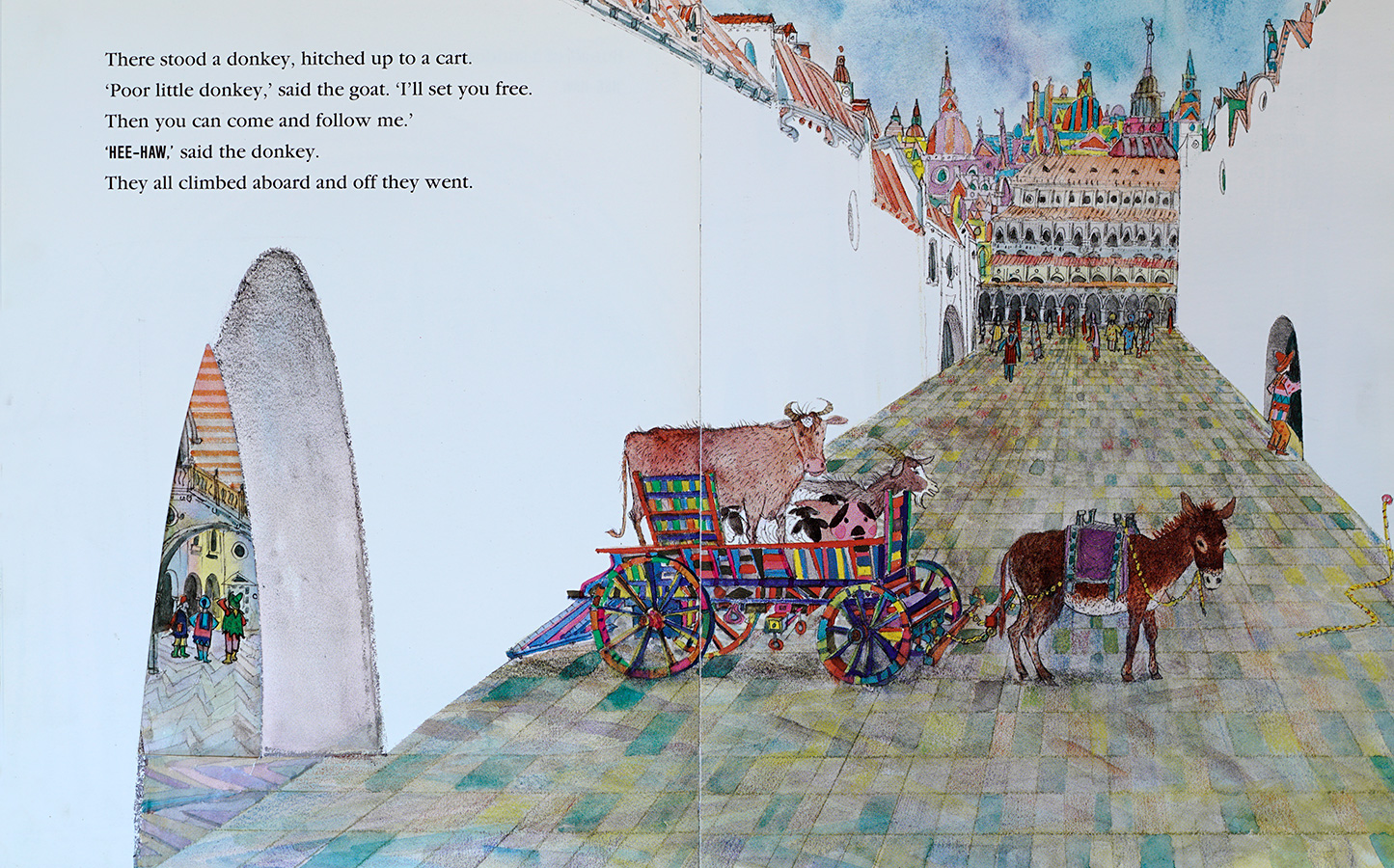

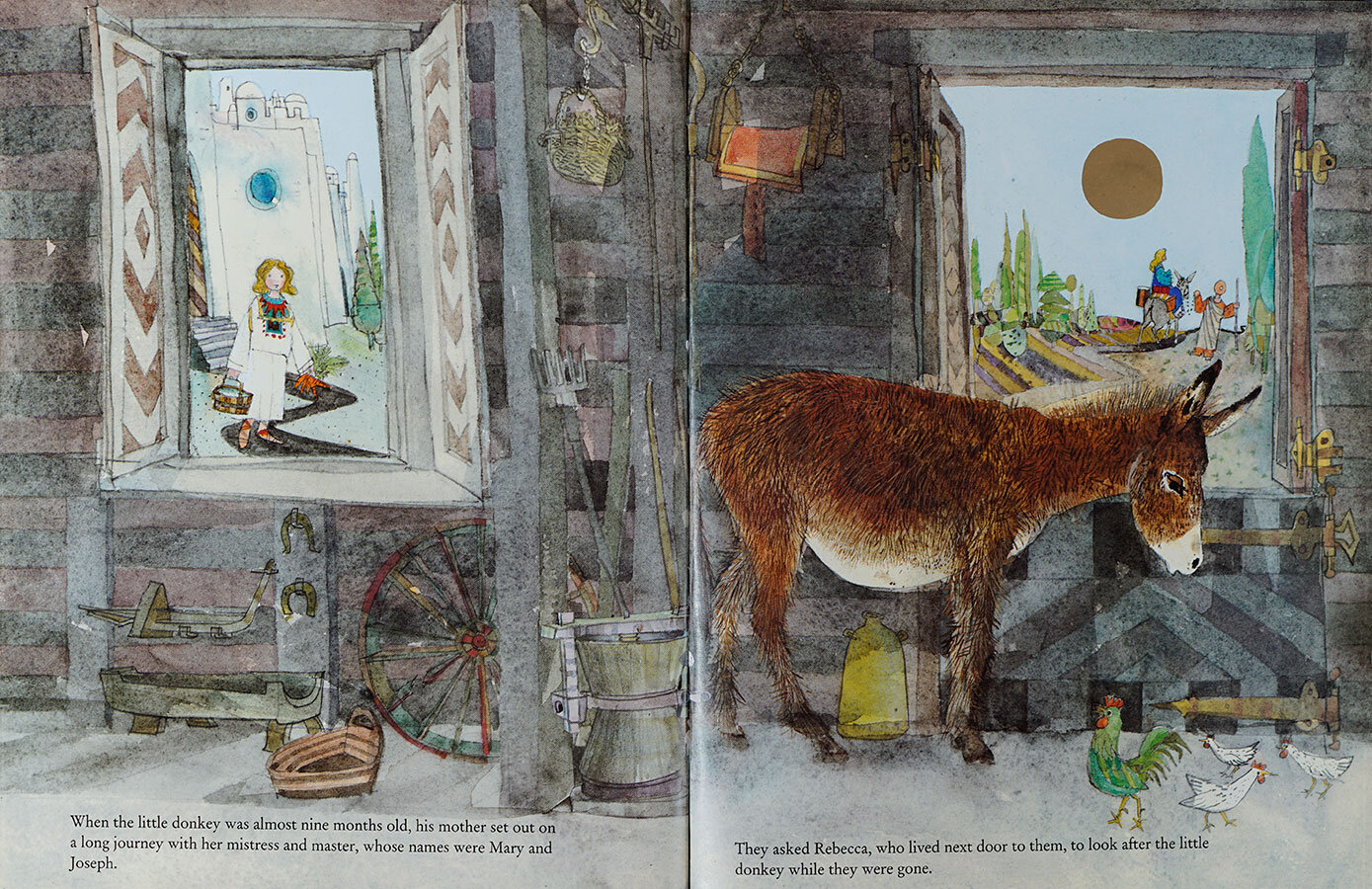

Goat’s Trail, 1986, uses a different method in that same pursuit of narrative flow, where shapes are cut out of the paper, most often within architectural elements, like windows and doors, into the preceding and ensuing events. This is the story of a curious mountain goat, who decides to investigate where the sounds from the valley below are coming from. He meets other animals on the way and, “I suppose,” wrote Brian, “the tale is an allegorical one showing how, by blindly following leaders, one can easily be duped and led into misfortune.”

Politically, Brian’s leaning was to the left, which is hardly surprising given his background and blood. His works also share many of the great visions of left-wing principles throughout modern times. He voted to the left, but was unsatisfied by all sides and mostly held political leaders in contempt with their power-hungry lunacies and self serving lies. He was fiercely independent intellectually and had worked hard to become so, physically as well. Nobody would tell Brian what to do! Having earned a good living obviously helped. Money to him had only one value, that of allowing him total creative independence with little space for compromise. Picasso famously had said he wanted to live “like a poor man with lots of money.” Well, “How many filet steaks can you eat in a day?” was Brian’s response to the avidity he so frequently witnessed in the changing social environment of the Côte d’Azur he had discovered in the early 70s, and loved for its landscape, sun and food, but not for the bling of so many of its rampantly voracious citizens. Like so many truly talented people he was humble about his achievements, not self effacing, but diametrically opposed in attitude to those whose fortunes had come from dealing in other people’s labour or creation and had the gall to boast about it. He loathed vulgarity. He respected talent, hard work, good manners and kindness. Money meant nothing more than a means to be free, to do what he wanted when he wanted. Oh yes, apart from allowing him to pick up the tab. He was always first to pick up the tab.

Designed to add narrative flow, Pelican, Daisy & Give a Dog a Bone use a split page technique, whilst in Goat’s Trail die-cut windows allow you to see parts of the following or preceding events and characters.

In 1988 he made a book about hope, only he used a different method than that habitually followed. “Usually my books are preconceived and worked out in pencil in a rough version before I start the final artwork. In the case of Carousel, each sequence I worked on dictated the following one, building up, page after page, towards a conclusion that I had not anticipated.” The story is about a little girl called Rosie who gets sick. It is a book about hope, destined for those bedridden children afflicted with illness… A story to help them along.

A selection of illustrations, including some originals, from Pelican, Daisy, Give a Dog a Bone, Goat’s Trail and Carousel.

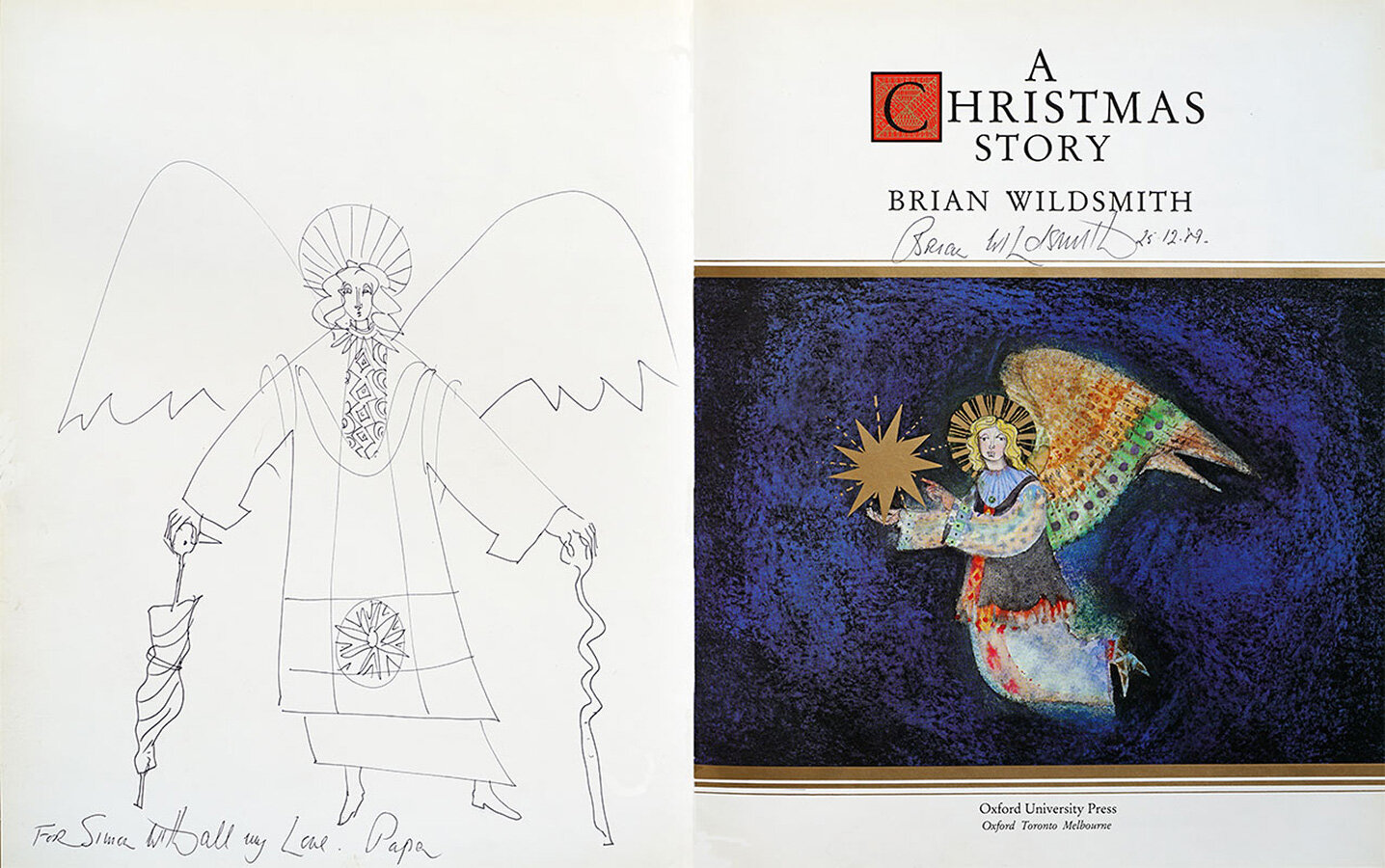

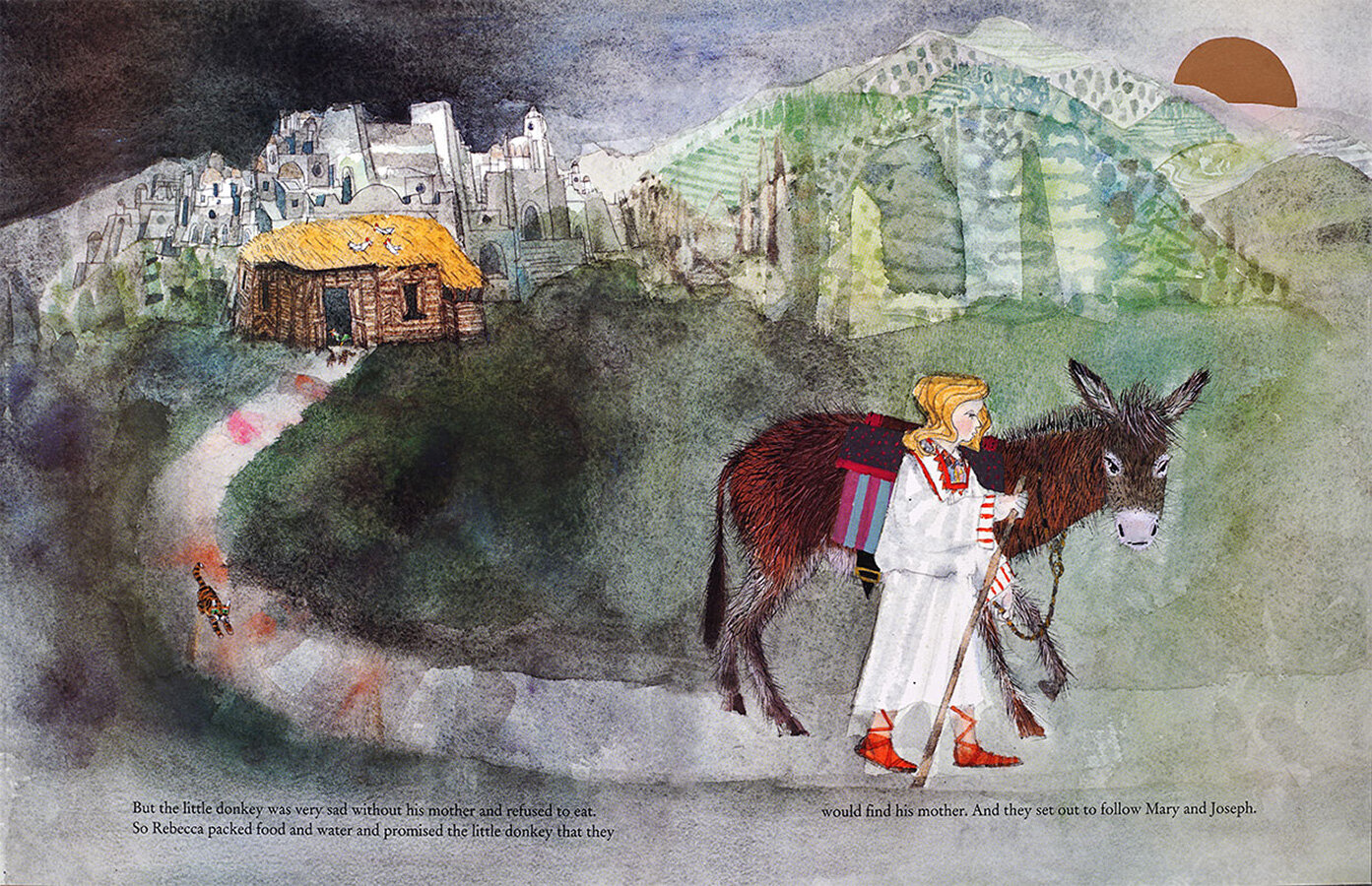

A TREASURED BOOK FOR CHRISTMAS

Brian signed off the eighties with A Christmas Story that received rave reviews: “A treasured picture book for Christmas,” Lichfield Mercury, “with glittering illustrations,” Independent on Sunday and “shimmering mosaics that throw gold dust in your eye and steal your heart away,” Eastern Daily Press. Further described as “powerfully mysterious,” The Sunday Times, or as “a visually stunning rendering of the story,” Books For Your Children. “Brian Wildsmith excels in his best selling Christmas Story,” Daily Telegraph.

For Christmas 2018 and Easter 2019, Oxford University Press published smaller and cheaper A5 editions of A Christmas Story, of Brian’s 1970s classic The Twelve Days of Christmas and of The Easter Story.

PAINTING

Untitled 172 X 172 cm. Oil and acrylic on sand and glue-textured canvas.

This abstract Mediterranean landscape hung in the family home in Castellaras from the moment the thick oil paint dried, until our parents’ deaths. It was our mother’s favourite and has never yet been exhibited.

It was not the 25 titles he had published this decade that lead Brian to say that he had reached ‘artistic maturity.’ Rather, and most importantly for him, it was the hundred or so paintings he had produced. He had finally realised the dream he had confided to Mabel George, his first editor at Oxford University Press back in the 1950s, notably his “longing to paint, and hope, through book illustration, to earn the freedom to achieve this ambition.”

“It has taken me a long time,” wrote Brian, “to feel ready and mature enough to confidently approach a blank canvas again. One of the reasons for this wait is the simple fact that I fell in love with making children's books. Another reason was of course financial. Having a wife and four children to support, I could not afford the luxury of spending my time painting without knowing where the next penny was to come from. Now my children have grown up and left home and the royalties from my books have allowed me that luxury.”

I WANT TO PRODUCE SOMETHING WORTH LEAVING ON THIS EARTH

During an undated interview with the journalist Edward Robinson, he had said, rather strangely, one might think, as if his work as an illustrator did not suffice, “For my own personal ego, I want to produce something worth leaving on this earth. After all there are limits to what is possible in a book for children. What I want to do has nothing to do with words, I can’t even really explain it, I just know it’s something entirely spiritual… expressing the spiritual quality of the sensations derived from observing nature, in some extraordinary way with paints, that will be entirely mine.” He had fallen in love with making books for children but there remained that need to create art for himself and himself alone. One whose limits or constraints were solely those of his own imagination, a reminder of his insatiable creativity.

Few people, fans or enthusiasts, are aware of these paintings which went on show, first at Schiller Wapner Gallery in New York City, in 1988, then at 871 Fine Arts in San Francisco, California. Several were sold in America before they were sent to Japan where ten were acquired by an affluent businessman who, in later years, was to become a major patron of Brian’s art. The rest are in the family collection or still on loan in Japan.

A selection of 12 of Brian’s paintings on canvas with details for six of them.

Douglas Martin, who interviewed Brian in Castellaras prior to these exhibitions wrote, “It is not surprising that an artist of Wildsmith's sensitivity and experience should have produced a corpus of paintings that have a claim to the highest international critical evaluation. He is painting with assurance, work that is positive in both physical and atmospheric presence, free from angst, facility, pretentiousness, obscurantism or artificial dogmatic additives. Difficult to describe, it is there to be enjoyed, but not to be underestimated in terms of its intellectual content.” How then does one describe these paintings Brian had repeatedly said were “intellectually unconnected from his approach to illustration?” He, who had always been interested in the sciences and for whom the line between science and art could often be blurred, knew he was looking to find a language to express the modern age: the one he chose was sculptural paintings - paintings in three dimensions “where virtually anything is permissible, where the capacity for self-delusion is an ever-present danger.”

He had said to Stephanie Nettell, “There is no connection whatsoever between my painting and my illustrations, except that they are done by the same hands and that they are both visual. The mental processes are so different that it is as if they are from two different lives. This is a new world and I need a new way of expressing myself.”

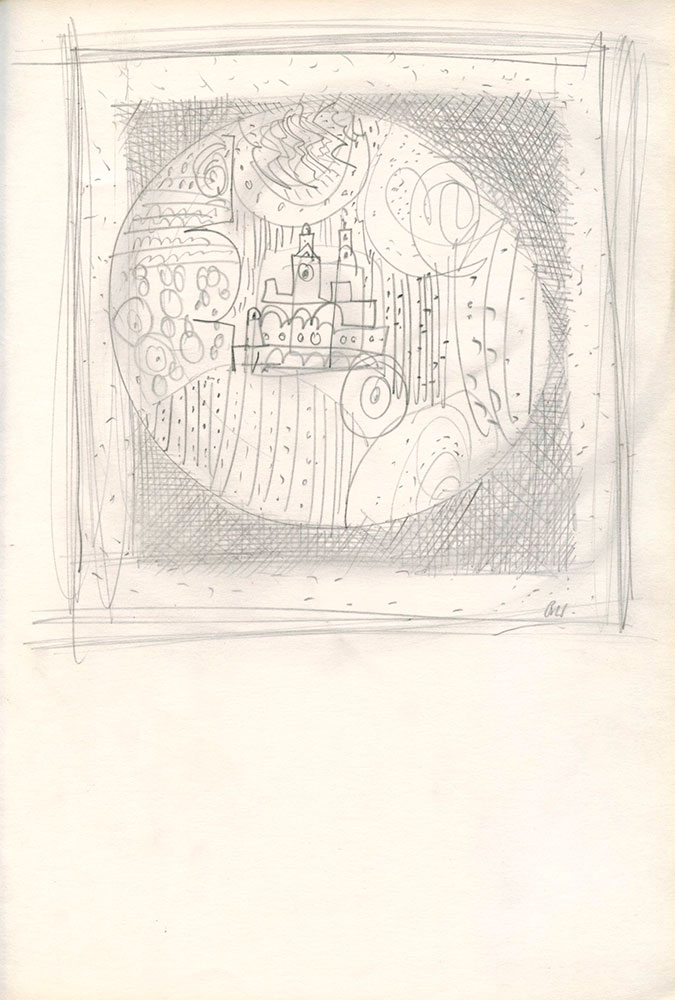

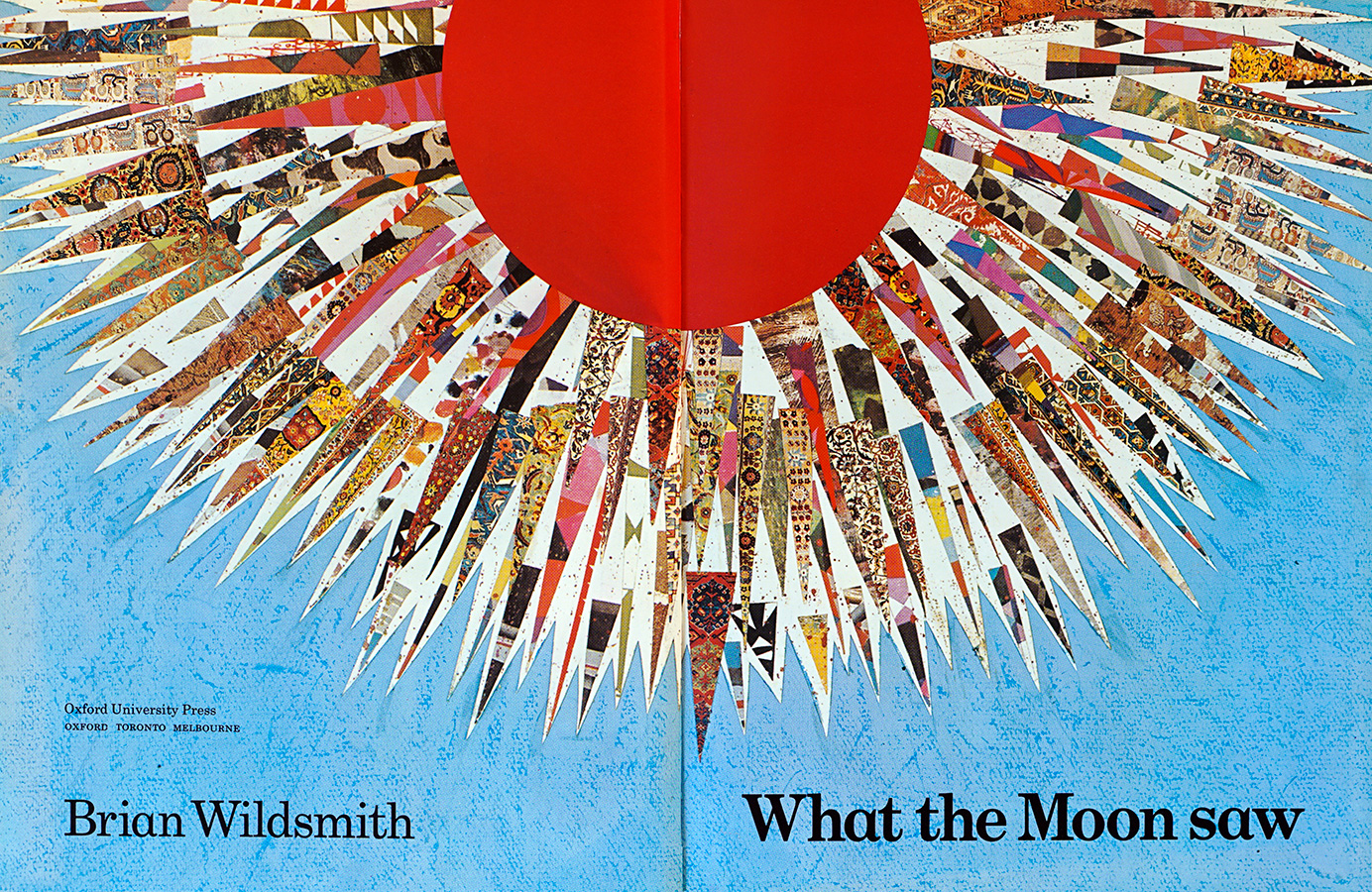

A selection of sketches, some of which were destined to become paintings on canvas.

THE VELVETEEN RABBIT

The year Brian had his first exhibition of paintings in New York, was also the year he got involved with the Oberlin Dance Company. It is a contemporary arts institution with longstanding roots in the San Francisco community. KT Nelson, director and choreographer for the company, knew Brian’s “rich palette of texture and imagery” through books she had read to her young son. She was not only sensitive to his “unbelievable imagination” but also, in her role as a performing artist, she felt “a certain kinetic energy in his work.” In her imaginative way of describing this phenomenon, KT said, “He took us into tree trunks, hid us in meadows, carried us across town squares and sent us into the heavens.” She proceeded to contact him, inviting him into The Velveteen Rabbit project. “He wrote back,” remembers KT, “on that old light blue airmail stationery in his artistic script and he said yes! I was thrilled.” Brian flew out to California where he spent a couple of weeks “drawing and painting all the costumes and sets required for the show.” According to a New York Times critic, the costuming plays a central role in allowing audiences to share the splendour and playfulness of the production, which is still staged today, and which, over the years, has attracted audiences of over 350 000.

Costumes Brian designed for The Velveteen Rabbit.

Study for The Velveteen Rabbit. Annotation: Velveteen Rabbit. Wizard in crystal ball. Perspex.